For the first time, astronomers have captured direct evidence of a hidden object orbiting an aging, massive red giant star. The discovery, made using the Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array (ALMA), sheds new light on how dying stars interact with their surroundings—and what unexpected dynamics might unfold during the final stages of stellar life.

The star in question is π1 Gruis, located about 530 light-years from Earth. It’s what’s known as an asymptotic giant branch (AGB) star—an evolved star that was once similar to the sun but has now expanded to a size over 400 times larger. Its brightness is staggering: thousands of times more luminous than our own sun, which has made it nearly impossible until now to observe anything in its immediate neighborhood. That’s precisely what makes this finding, published in Nature Astronomy, so striking.

A Surprisingly Circular Orbit

Of all the unexpected aspects of the study published in Nature Astronomy, the shape of the companion’s orbit stood out most. Based on earlier models, scientists expected a more elliptical orbit, which would make sense given the chaotic and high-energy environment around an AGB star. Instead, what they observed was a nearly perfect circle.

A circular orbit suggests that tidal interactions, the gravitational forces that tend to smooth out orbits over time, might be happening more quickly or efficiently than previously thought. That, in turn, could signal the need to recalibrate many existing models of how stars and their companions evolve together.

This level of detail was only possible because of ALMA’s unmatched resolution. The telescope array, made up of 66 radio dishes in Chile’s Atacama Desert, was able to visually confirm the motion of the companion despite the overwhelming brightness of π1 Gruis. According to Phys.org, this is the first time such an orbit has been directly observed around a red giant of this type.

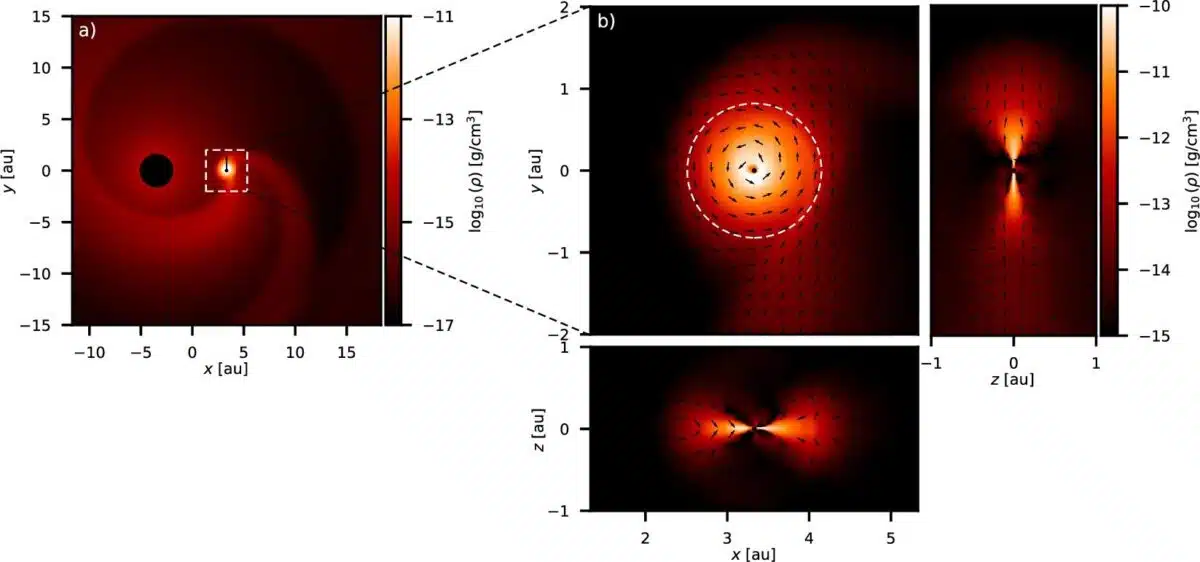

Hydrodynamic model of the accretion disk surrounding the companion of π1 Gruis. Credit: Nature Astronomy

Hydrodynamic model of the accretion disk surrounding the companion of π1 Gruis. Credit: Nature Astronomy

Pinpointing the Mass to Chart the Orbit

Before the team could fully interpret their observations, they first had to determine the mass of π1 Gruis—a challenging task given the star’s bloated, pulsating state. This step was carried out by researchers at Monash University, including PhD student Yoshiya Mori, who used stellar evolution models to analyze its brightness and pulsation behavior.

“A key part of understanding the orbit of the companion is knowing the mass of the AGB star,” Mori said. Without that parameter, aligning the observed motion with theoretical models would have been impossible.

compared their simulations with existing models from the scientific literature, concentrating on the late-stage evolution of red giants. Mori added that introducing a companion into an already unstable system “could possibly wreak further havoc on the already complicated processes surrounding these stars.”

Astronomers using ESO’s Very Large Telescope have for the 1st time directly observed patterns on the surface of a star outside the Solar System. The PIONIER instrument reveals the convective cells on the surface of the star (π1 Gruis) whose diameter is 350 times that of the Sun. pic.twitter.com/qKw3yFk6nv

— bill bold (@bill_bold) January 25, 2018

The Case for Revising Late-stage Stellar Models

Traditional models assumed that orbital circularization takes thousands to millions of years. The case of π1 Gruis shows a companion already in a circular orbit. According to Mats Esseldeurs, the project’s lead scientist from KU Leuven, these findings could prompt a broader reassessment of how tidal forces operate and how binary systems evolve over time.

“Understanding how close companions behave under these conditions helps us better predict what will happen to the planets around the sun, and how the companion influences the evolution of the giant star itself.”

And the implications reach far beyond a single star. If similar companions are common around other dying stars, current models may need to be reevaluated on a much larger scale.