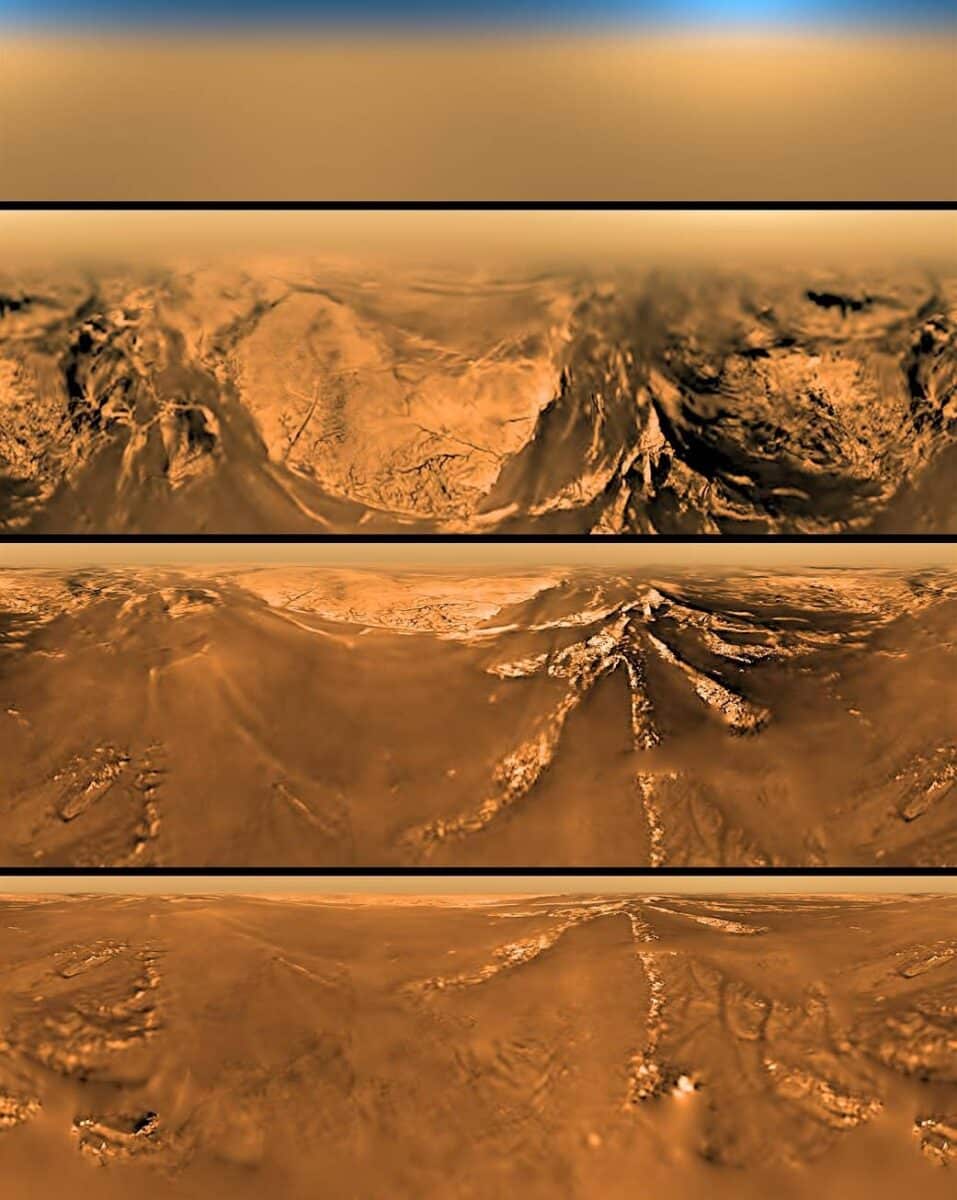

In January 2005, a small European-built probe made planetary history when it pierced the thick orange haze of Titan, Saturn’s largest moon. Delivered by NASA’s Cassini spacecraft, the Huygens lander became the first—and to date only—mission to land on a body in the outer solar system.

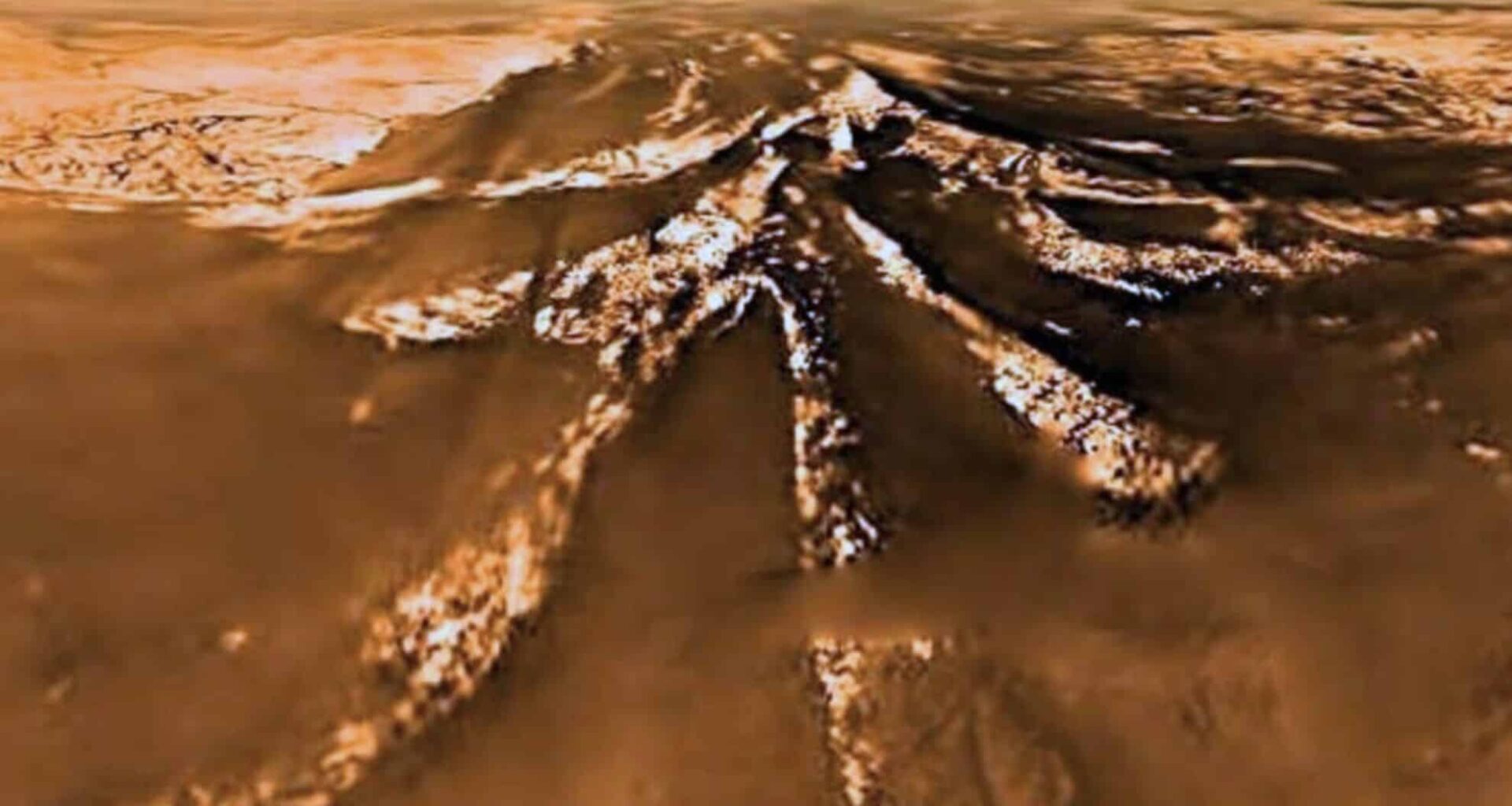

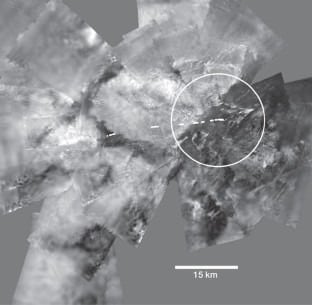

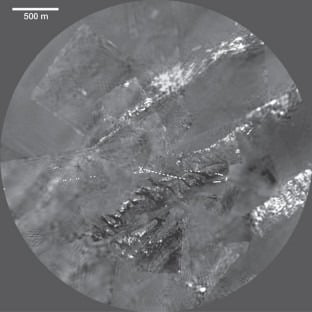

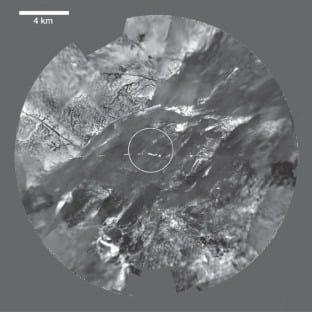

Among the hundreds of measurements and images captured during its descent, one photograph remains a focal point of scientific uncertainty. Taken just 8 kilometers above the surface, the image reveals branching channels etched into Titan’s icy terrain. Two decades later, that image continues to defy definitive explanation.

While the terrain clearly shows evidence of fluvial erosion, researchers have yet to reach consensus on how the features formed, or what exact liquid carved them. Titan, after all, is far too cold for water to flow. Instead, the prevailing theory points to liquid methane acting much like water does on Earth—raining down, collecting in rivers, and draining into lakes.

Methane Rivers on an Alien World

The surface Huygens landed on—near the equatorial region known as Adiri—resembled a dried-up river delta. The Descent Imager/Spectral Radiometer (DISR), described in a foundational Nature study revealed a branching network of channels resembling terrestrial drainage patterns.

These formations imply past or even recurring liquid flow. But on Titan, it isn’t water carving the terrain—it’s liquid methane and ethane. The Cassini Arrival Press Kit and official NASA retrospective confirmed that the surface was made of icy grains, and that methane behaves as a liquid at Titan’s frigid average temperature of –179°C.

Laboratory experiments and atmospheric models support this mechanism. According to the GCMS results, Titan’s atmosphere is 98.4% nitrogen and 1.4% methane, closely matching early Earth’s composition—minus the warmth and liquid water.

Though the image clearly shows geomorphological features consistent with erosion, the exact timing, frequency, and mechanisms driving the methane flows remain unknown. Was this surface shaped by seasonal methane rainfall? By ancient floods? Or possibly by cryovolcanic activity that mimics fluvial patterns but originates from internal geological heat?

Chemistry of a Primitive Earth, Frozen in Time

Beyond surface morphology, the chemistry of Titan’s atmosphere also points to intriguing parallels with a young Earth. As confirmed by the Gas Chromatograph Mass Spectrometer (GCMS) results, detected methane and trace amounts of heavier hydrocarbons but no signatures of biological activity. This absence continues to fuel debates about whether Titan is prebiotic—or simply alien.

The surface haze, composed of tholins—complex organic compounds formed by solar ultraviolet light reacting with methane—is considered a potential building block for life. The Aerosol Collector Pyrolyser experiment, as detailed in Nature, revealed that these particles contain carbon and nitrogen-rich cores.

Data from the wind profile analysis showed that Titan’s winds near the surface were unexpectedly calm, a trait that supports the slow accumulation of organic particles and further enables surface chemistry that may resemble early Earth’s own prebiotic conditions.

All of this points to Titan as a natural lab for studying abiotic organic synthesis under conditions we cannot replicate on Earth—a frozen archive of planetary evolution, rich in carbon-based molecules.

A 72-Minute Transmission That Reshaped Planetary Science

The Huygens mission lasted just over an hour on the surface. But in those 72 minutes, the probe delivered an unprecedented dataset. Surface data from the Surface Science Package, summarized in NASA’s 10-year retrospective, described a soft impact, a slight tilt, and a terrain composed of water-ice pebbles set in a substrate with the consistency of damp sand.

The DISR captured a sequence of images at four altitudes, which were then compiled into a descent mosaic. That single critical frame—taken from 8 km above—remains the most debated. The landscape it captures shows clear channels and flow patterns. Yet without longer-term monitoring or mobility, there was no way to determine whether the features were carved recently or are relics from an earlier, more dynamic epoch.

In fact, later radar studies from Cassini revealed massive methane lakes like Ontario Lacus and Kraken Mare near Titan’s poles. But Huygens’ equatorial location showed no such large bodies nearby, adding complexity to the image’s interpretation. Was the erosion ancient? Was the image capturing a rare equatorial rain event? The science remains unsettled.

Dragonfly: A Flying Laboratory for an Unresolved World

NASA’s upcoming Dragonfly mission—scheduled for launch in 2028 and arrival in the mid-2030s—marks a shift in strategy. Rather than a stationary lander, Dragonfly will be a rotorcraft lander, able to traverse Titan’s surface by hopping between dozens of sites across the moon’s equatorial dune fields.

Dragonfly will carry advanced instruments to analyze Titan’s surface chemistry, especially for signs of complex organics and possible precursors to metabolism. The mission’s science objectives, as outlined on NASA Science’s Dragonfly mission page, include probing the chemical pathways that might lead to life—not just on Titan, but across the galaxy.

The target site, Shangri-La, is rich in hydrocarbon dunes and offers access to ancient terrain believed to preserve some of Titan’s oldest surface materials. In contrast to Huygens’ brief surface encounter, Dragonfly is expected to operate for multiple years, transforming a 90-minute snapshot into a planetary-scale field study.