November 14, 2025• Physics 18, 182

Experiments reveal the surprisingly large amount of entropy—and thus heat—generated by a clock that could be part of a quantum processor.

CreativeHub/stock.adobe.com

Entropy generator. Any timekeeping device, such as an hourglass, generates heat and entropy through an irreversible physical process.

CreativeHub/stock.adobe.com

Entropy generator. Any timekeeping device, such as an hourglass, generates heat and entropy through an irreversible physical process.×

As a clock records the passage of time—for example, by counting the swings of a pendulum—it automatically generates entropy and thus heat. The effect is usually small, but for the quantum-scale clock operations that will be needed in future quantum processors, the link between timekeeping and heat production may be important. Now, using a clock built from two single-electron traps known as quantum dots, researchers have measured the entropy produced by the act of recording a clock’s ticks [1]. They found that this process generates far more entropy and heat than the clock’s quantum operations. The researchers hope that the work will provide clues to building more practical quantum technology.

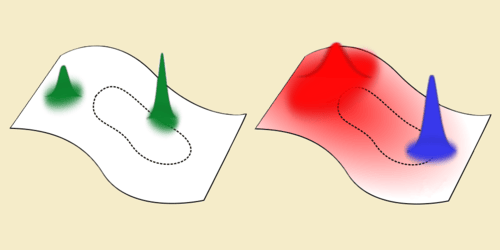

The second law of thermodynamics demands that any clock generates entropy in its timekeeping operation, says Florian Meier, a PhD student at the Technical University of Vienna. This entropy results from a force pushing a system irreversibly in one direction, such as a spring turning clock hands or gravity driving sand grains through a hole. But at the nanoscale, thermal fluctuations are significant, and one can imagine a clock without such a force. For example, an electron could hop from one quantum dot to a neighboring one and then back, and a clock could register a “tick” with each hop. Such hops would be reversible and wouldn’t generate entropy. “This observation seems to be at odds with the principle that clocks always dissipate energy and create entropy,” says Meier.

In an attempt to resolve this paradox, Meier teamed up with Natalia Ares and colleagues at the University of Oxford in the UK to build a so-called quantum clock that would allow them to measure the entropy generation. Meier, Ares, and their colleagues devised a clock based on a quantum-dot pair. Each tick occurs when the clock moves through a complete cycle of three states and returns to the start: state 0, where each dot is unoccupied; state L, where a single electron is on the left dot; and state R, where the electron has hopped across to the right dot. At each step, the system can move forward or backward, but applying appropriate voltages to the dots can shift the probabilities for moving the cycle in either direction.

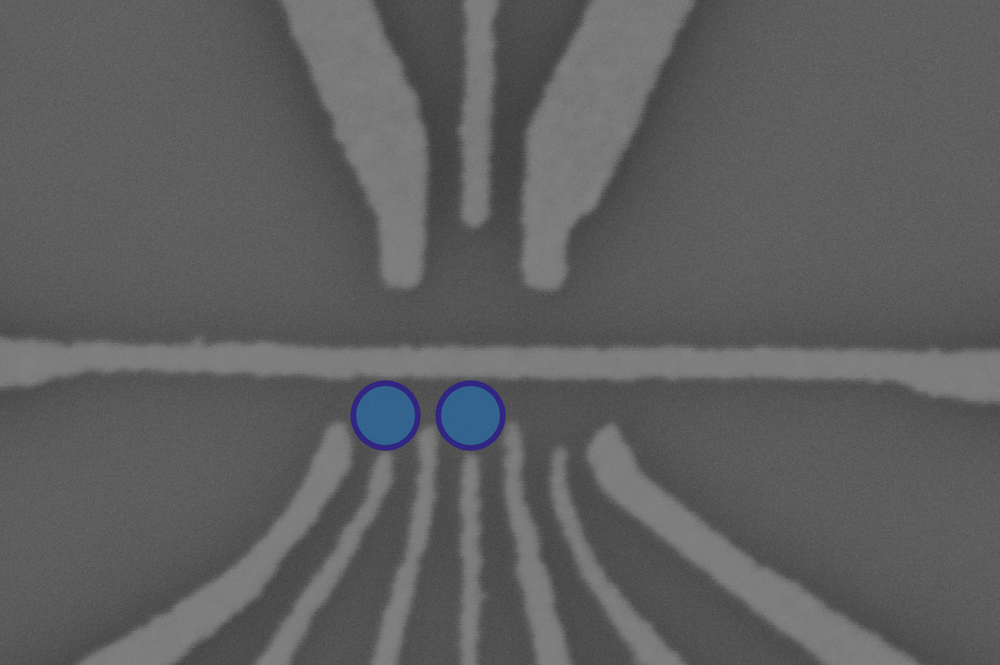

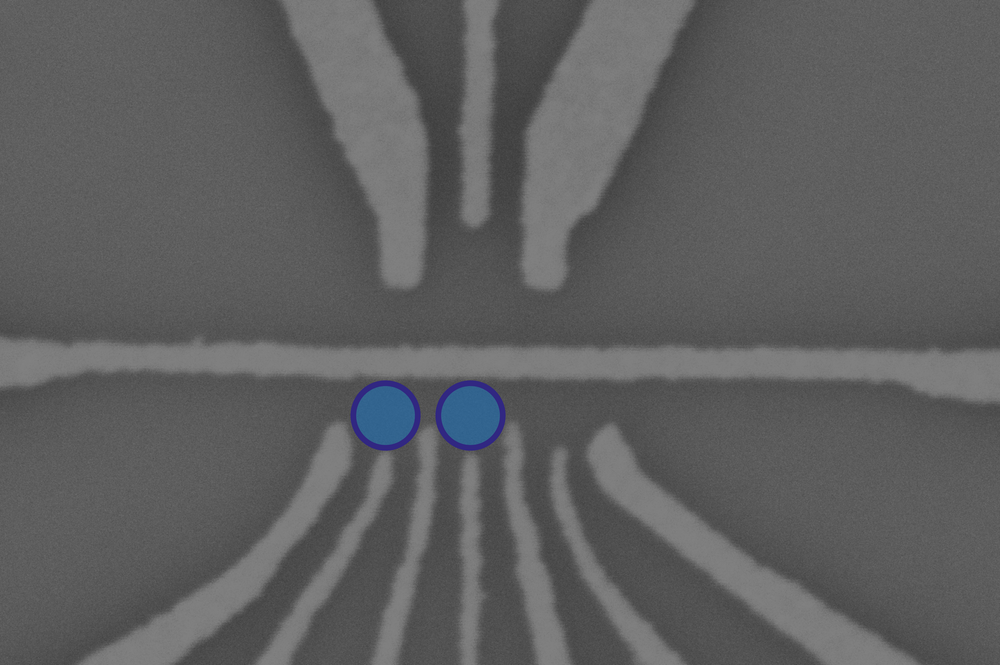

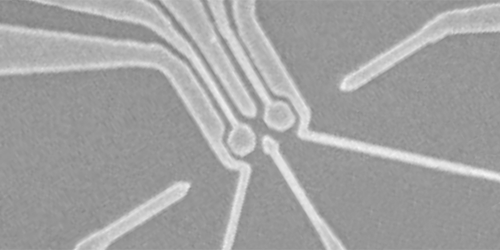

Y. Schell and G. Katsaros/Institute for Science and Technology Austria

Quantum ticking. Each of the two quantum dots (blue) in the quantum clock is a region of semiconductor that can host a single free electron and that can be influenced by voltages applied nearby.

Y. Schell and G. Katsaros/Institute for Science and Technology Austria

Quantum ticking. Each of the two quantum dots (blue) in the quantum clock is a region of semiconductor that can host a single free electron and that can be influenced by voltages applied nearby.×

The team monitored the state of the clock by measuring current flowing to a nearby “charge-sensor” dot in response to a separate applied voltage. Each of the three states produced a different current value, but distinguishing these values required sufficient current. Increasing the applied sensor voltage increased the current and led to a cleaner signal. However, higher current also led to the generation of more heat and entropy. The researchers could precisely control and determine this entropy cost of measuring and recording the clock signal.

A similar trade-off between quality and entropy generation has been observed previously for the regularity of the ticks of a quantum clock but has not been shown for the measurement of a clock signal. And this entropy cost was a billion times larger than the entropy generated by the cycling of the quantum clock, Ares says.

This large entropy generation turned out to be the solution to the apparent paradox. Even if the double-quantum-dot voltage is set to zero—meaning that there is no net forward or reverse cycling of the clock, and the ticking generates no entropy—a useful time signal can still be extracted, the team found. The second law is not violated because entropy is produced in the measurement by the sensor dot.

Ares says that the work highlights a profound challenge facing the development of quantum technology: To harness these delicate machines for computers or sensors, researchers will need ways to monitor their states without producing so much heat in the measurement process. “By establishing that tick extraction generally dominates the entropic cost of timekeeping,” Ares says, “our work may guide future microscopic-clock designs to improve their precision in the most thermodynamically efficient way.”

“Any realistic understanding of the energy costs of running a clock must include the apparatus between the ticker inside it and the classical ticks that come out,” says Edward Laird, an expert in quantum electronic devices at the University of Lancaster in the UK. The value of the current work, he says, is that it studies an elegant model clock in which the ticker and the measuring apparatus are part of different circuits. “The results will be useful for understanding the ultimate running costs of different kinds of clocks, including those used to synchronize [operations on] computer chips.”

–Mark Buchanan

Mark Buchanan is a freelance science writer who splits his time between Abergavenny, UK, and Notre Dame de Courson, France.

ReferencesV. Wadhia et al., “Entropic costs of extracting classical ticks from a quantum clock,” Phys. Rev. Lett. 135, 200407 (2025).More InformationEntropic Costs of Extracting Classical Ticks from a Quantum Clock

Vivek Wadhia, Florian Meier, Federico Fedele, Ralph Silva, Nuriya Nurgalieva, David L. Craig, Daniel Jirovec, Jaime Saez-Mollejo, Andrea Ballabio, Daniel Chrastina, Giovanni Isella, Marcus Huber, Mark T. Mitchison, Paul Erker, and Natalia Ares

Phys. Rev. Lett. 135, 200407 (2025)

Published November 14, 2025

Subject AreasQuantum PhysicsStatistical PhysicsRelated Articles

Quantum InformationQuantum Scars UnmaskedNovember 12, 2025

Quantum InformationQuantum Scars UnmaskedNovember 12, 2025

A new approach finds useful patterns called quantum scars in the complex dynamics of quantum many-body systems. Read More »