The study, led by researchers at Florida State University, explores how electrons behave in two-dimensional materials when subjected to specific quantum conditions. Their findings highlight a phase transition where some electrons become immobile, forming a crystal lattice, while others move freely, creating an exciting “pinball” effect.

The Quest for Electron Crystals

For years, scientists have known that under certain conditions, electrons in 2D materials can form regular, crystal-like structures, known as Wigner crystals. In these phases, electrons typically arrange themselves in a stable pattern, and the material stops conducting electricity.

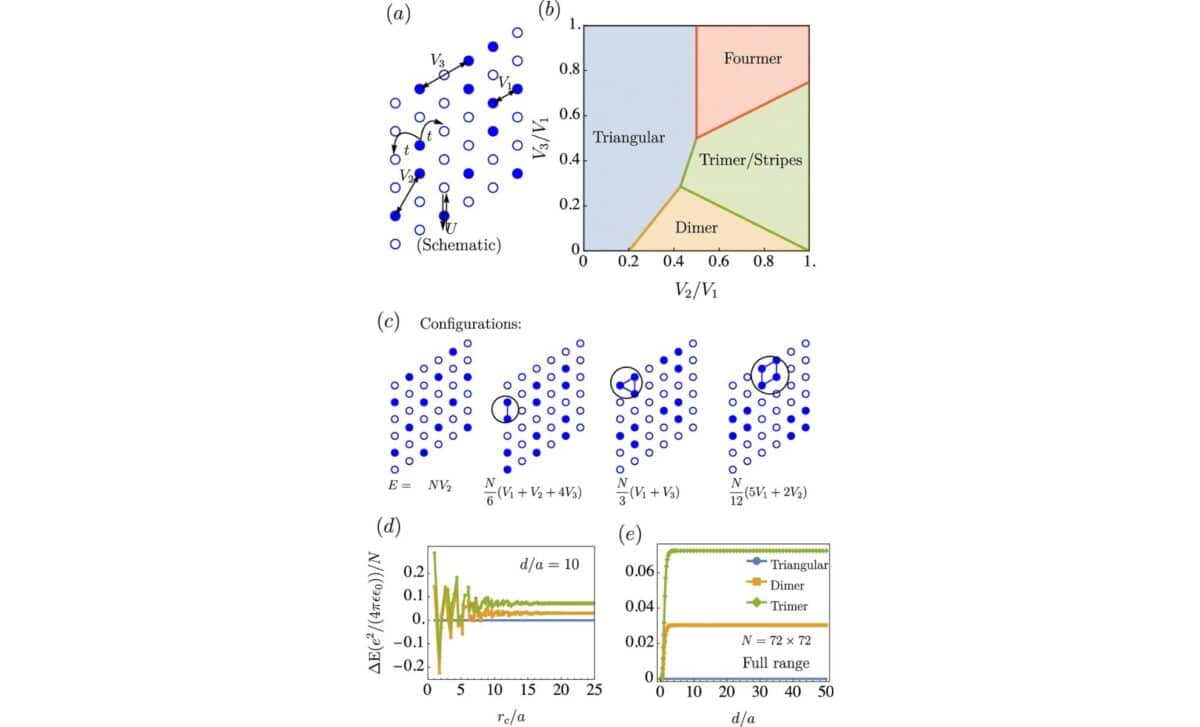

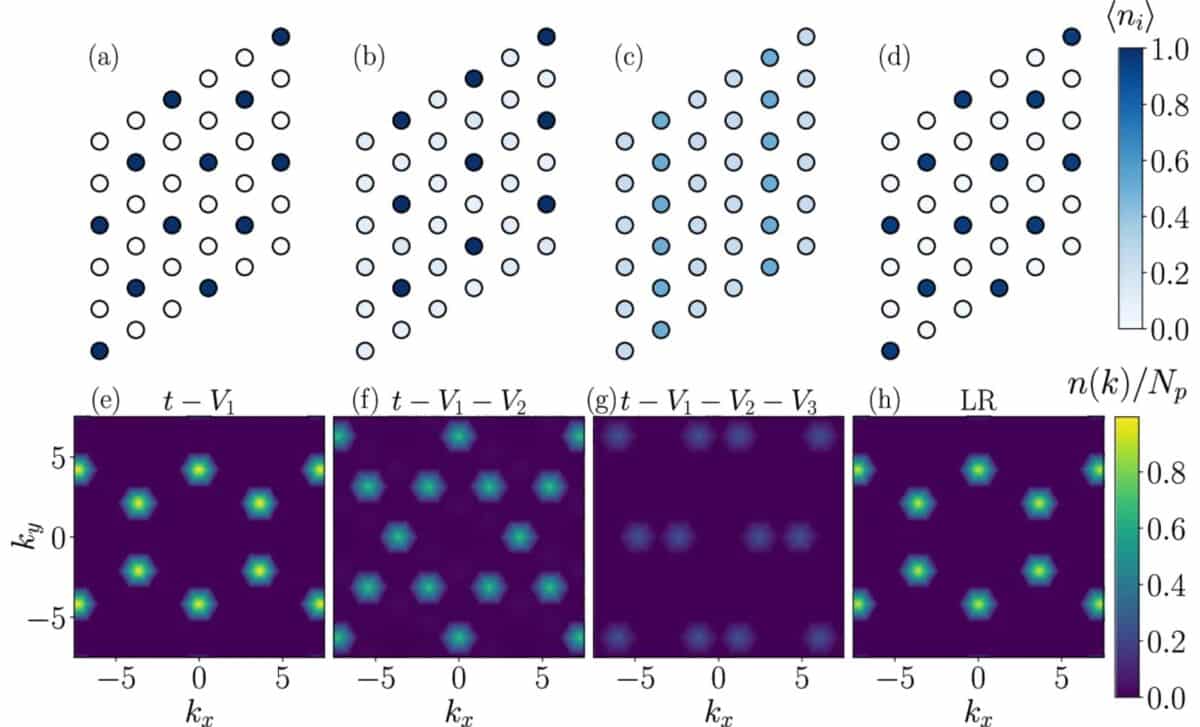

However, these crystalline states are still not fully understood, particularly when other quantum effects come into play. According to the team of researchers, the key to understanding these behaviors lies in tuning specific quantum parameters, what they refer to as “quantum knobs“, that allow electrons to transition between rigid crystal structures and more fluid forms.

The researchers, using advanced computational tools at Florida State University, explored how changes in energy scales affect the formation of these generalized Wigner crystals. Unlike traditional Wigner crystals that only form triangular patterns, these newly discovered structures allow for different geometric shapes, like stripes or honeycombs, to emerge. The findings, published in npj Quantum Materials, provide valuable insights into how quantum materials can be engineered for new applications in technology.

The Pinball Phase: A New State of Matter

In their investigation, the physicists also identified a surprising new state of matter: the “pinball” phase. This state occurs when electrons exhibit both insulating and conducting properties simultaneously. Some electrons remain anchored in the crystal lattice, while others move freely, similar to a pinball ricocheting between fixed posts. This discovery marks the first time such a hybrid behavior has been observed in a material at the electron density studied, offering new opportunities for manipulating electron behavior in quantum systems.

“This pinball phase is a very exciting phase of matter that we observed while researching the generalized Wigner crystal,” said Cyprian Lewandowski, one of the lead authors of the study. According to Lewandowski, the ability to control these competing behaviors, insulating versus conducting, could revolutionize future quantum devices, where electron mobility and confinement are crucial.

Implications for Quantum Technologies

The ability to control the transition between solid and liquid states in materials opens the door to advances in various fields, from quantum computing to superconductivity. As the researchers point out, understanding how and why certain electron states are favored over others could lead to breakthroughs in the development of ultra-efficient electronics and high-performance materials used in medical imaging, energy storage, and even atomic clocks.

The work highlights a broader trend in condensed matter physics: the search for ways to manipulate quantum materials to control their properties with precision. “We’re looking to predict where certain phases of matter exist and how one state can transition to another,” Lewandowski said. These discoveries could help scientists engineer new materials with desired electronic properties, which could eventually find their way into the next generation of quantum technologies.

As scientists continue to explore these quantum states, the potential applications grow clearer. This research could play a pivotal role in developing more efficient quantum computers, where electron behavior is central to the functioning of quantum bits, or qubits. Moreover, by unlocking new methods of controlling electron flow and material states, the findings could pave the way for better superconductors, which could revolutionize energy storage and transfer systems.