The legendary pitcher Leroy “Satchel” Paige once remarked, “Don’t look back. Something might be gaining on you.” It’s one of the great bons mots on the subject of aging, and particularly fitting coming from a man who threw his last professional pitches at the age of 59. Much like sports, music tends to be a young person’s game, and especially so since the earliest years of the rock ’n’ roll era, when artists like Chuck Berry, the Coasters, and Eddie Cochran found pay dirt by mining a hitherto underexplored topic in American song: teenage angst. In the mid-1950s, the idea that the cutting edge of pop would come to be dominated by relatively young people writing songs for and about people even younger was a revolutionary notion, one that in the next decade would come to be taken for granted. “I hope I die before I get old,” the Who’s Roger Daltrey sang back in 1965, coining a slogan for a genre—though, 60 years and many millions of dollars later, he’s likely glad his wish failed to come true. Even as septuagenarians and octogenarians like Bruce Springsteen and the Rolling Stones, respectively, continue to tour to ever-more-astounding box-office receipts, they’re doing so largely on the back of music they made 40, 50, even 60 years ago. Rock has always had a lot more to say about being (and staying) young than it ever has about growing old.

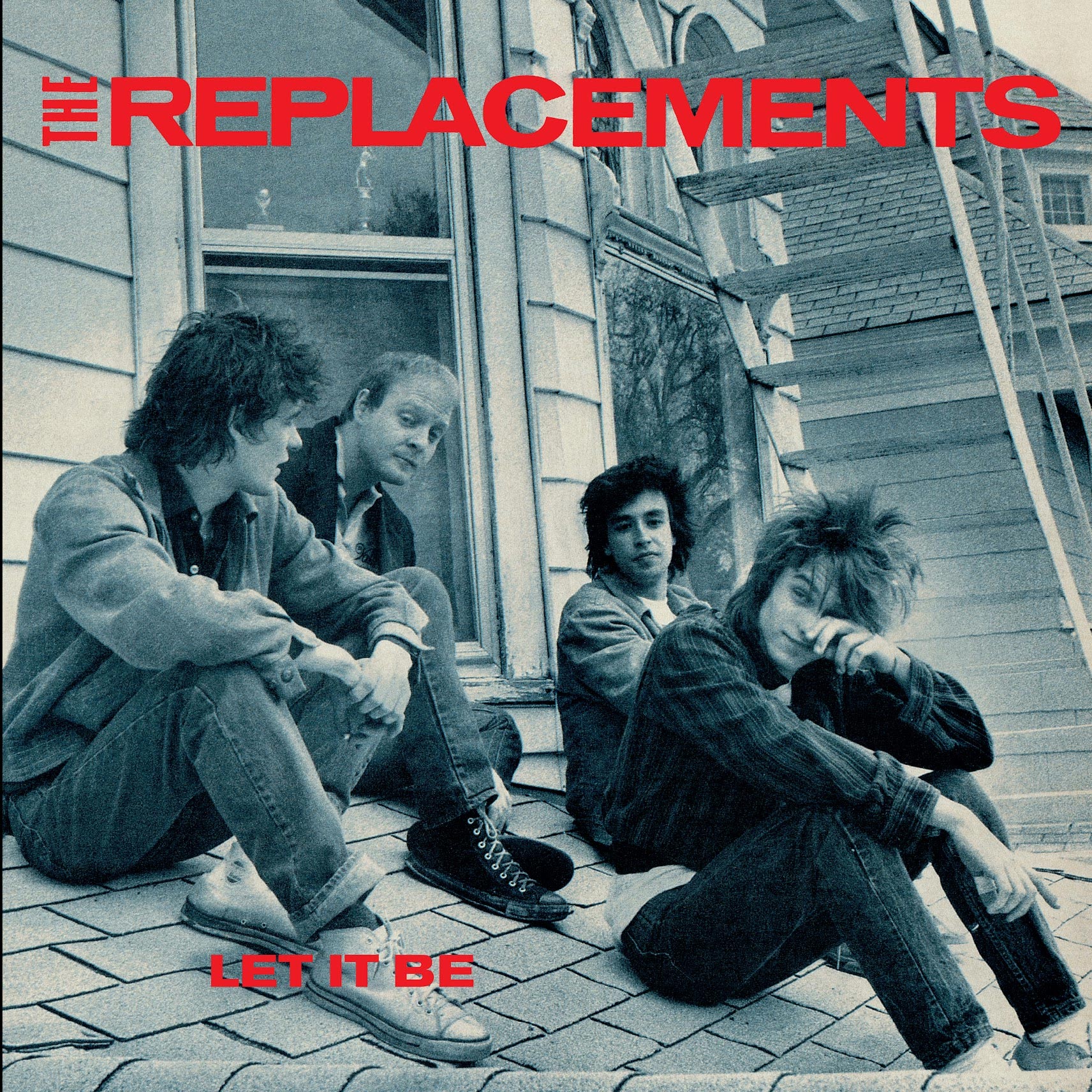

It’s no small achievement, then, that the Replacements’ 1984 masterpiece Let It Be might be the greatest rock ’n’ roll album ever made about growing up, if not exactly getting old. (Three of the band’s four members—rhythm guitarist and singer-songwriter Paul Westerberg, lead guitarist Bob Stinson, and drummer Chris Mars—were still in their early 20s when they began recording it; the fourth, bassist Tommy Stinson, was only 16.) Let It Be, which receives a lovely, deluxe-edition reissue from Rhino this week, was the band’s fourth official release, after 1981’s Sorry Ma, Forgot to Take Out the Trash, the 1982 EP Stink, and 1983’s Hootenanny. But it’s where the legend of one of rock’s most star-crossed bands takes root, an album that drew rapturous critical acclaim—a four-star review from Rolling Stone and a fourth-place showing in the Village Voice’s Pazz & Jop year-end critics’ poll, above such era-defining blockbusters as Van Halen’s 1984 and Cyndi Lauper’s She’s So Unusual—while failing to even sniff the Billboard Top 200.

It is one of popular music’s most breathtaking quantum leaps forward.

The new edition of Let It Be includes a remastered version of the original album, a sizable helping of previously unreleased demos and alternate takes, and a previously bootlegged 28-song live performance from Chicago in March 1984. There’s nothing here that’s quite as revelatory as the brand-new mix of 1985’s Tim that accompanied that album’s deluxe reissue back in 2023, but that’s OK. The live set is spirited and thrilling, even if the recording quality leaves something to be desired; the alternate takes and outtakes are interesting marginalia, although I doubt that anyone who’s ever heard Let It Be has spent much time wondering whether the best takes from those sessions made it onto the album. The set also includes an expansive essay by the wonderful critic and musician Elizabeth Nelson, and another, shorter missive from Peter Jesperson, the band’s former manager and co-producer, and the co-founder of Twin/Tone Records, the famed Minneapolis indie label that first released Let It Be 41 years ago.

Slate receives a commission when you purchase items using the links on this page.

Thank you for your support.

Over the years, many fans and critics have pointed to the previous year’s Hootenanny as a crucial predecessor to Let It Be, in terms of the Replacements starting to take themselves and their audience a bit more seriously than they had on their earlier, furiously impetuous hardcore and hardcore-adjacent releases. There’s certainly something to this: Hootenanny highlights like “Color Me Impressed” and “Within Your Reach” found the boys ascending to new levels of focus and control, both musically and lyrically.

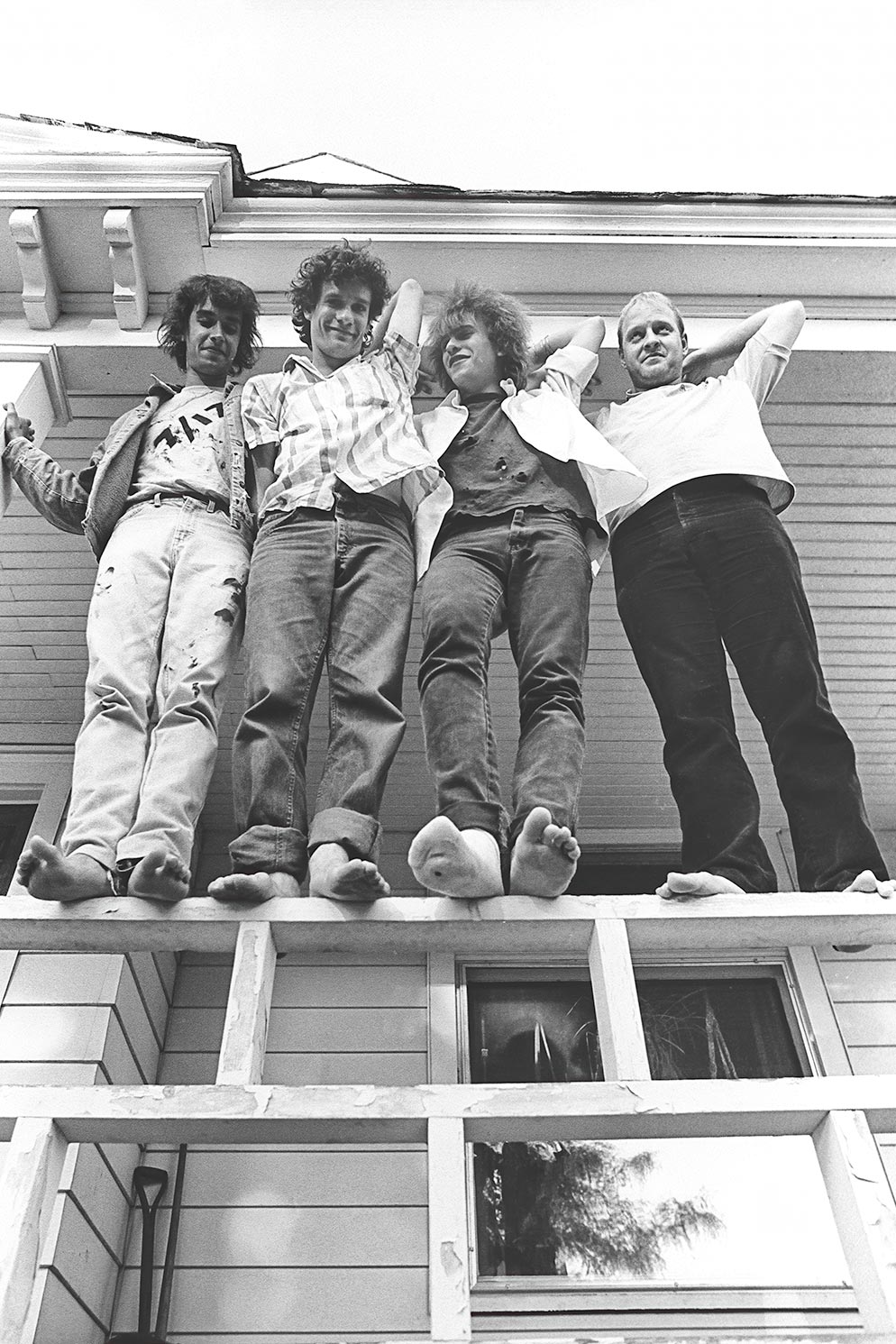

Greg Helgeson

But this assessment also tends to overly benefit from hindsight. The truth is that there’s relatively little on Hootenanny, or anywhere else in the band’s prior oeuvre, that suggests that Westerberg and his ’Mats mates had a work like Let It Be in them. It is one of popular music’s most breathtaking quantum leaps forward. Let It Be is an album about life and art becoming realer, more meaningful but also more complicated, and the strange feelings this evolution provokes. In his notes for the box set, Jesperson recalls Westerberg shuttling demo tapes of incredible song after incredible song to his manager and mentor in the dead of night, demanding that Jesperson hold them because Westerberg was worried that if he kept them in his own house, he’d have second thoughts and erase them—the seriousness and sincerity of what he was writing was genuinely freaking him out.

Let It Be’s most famous track may be its opener, “I Will Dare,” which also served as the album’s only single. “How young are you? How old am I?/ Let’s count the rings around my eyes,” sings Westerberg; this killer opening line also serves as a sort of mission statement for everything to come. The ambivalence and insecurity that haunt that nether region between adolescence and adulthood are the defining theme of Let It Be, explored most often through the lens of relationships. “Everything you dream of is right in front of you/ And everything is a lie,” sings Westerberg on “Unsatisfied.” “Sixteen Blue,” a spiritual inheritor of Big Star’s classic “Thirteen,” finds Westerberg imparting rueful wisdom to an unnamed teenage subject: “Your age is the hardest age/ Everything just drags and drags,” he rasps on the song’s refrain, a perfect crystallization of how teenaged-ness is not just fleeting but, paradoxically, interminable. The album’s closer, “Answering Machine,” might be the finest song ever written about a quintessentially postadolescent pastime: the lovelorn drunk dial.

Then there’s “Androgynous,” Westerberg’s ode to gender fluidity, which was the most astonishing recording the ’Mats had made to date. Its austere arrangement of little more than a vocal and a slyly propulsive piano can’t help but recall another stunner by a fellow Minnesotan, Prince’s “How Come U Don’t Call Me Anymore?,” released as the B-side to “1999” just two years earlier. “Androgynous” is an entirely beautiful song, both righteous and elusive, full of piercing insight and lump-in-your-throat imagery that’s wry and aphoristic enough to be about anyone and everyone. As Nelson writes, the song’s power “is less about doctrinaire proclamations and more about the way it renders and romanticizes the outsider.” It’s one of the great works of unadorned humanism in the rock canon.

None of which is to say that Let It Be lacks humor—far from it. Look no further than its title, a joke that’s as funny today as it was 41 years ago. “Tommy Gets His Tonsils Out” is the greatest punk song ever written about ENT doctors; “Gary’s Got a Boner” is basically a premeditated thumb-in-the-eye to every critic who’d go on to praise the band’s newfound maturity. One of my favorite tracks on the album is “Seen Your Video,” the first three-quarters of which is a wordless and unexpectedly gorgeous instrumental before the song reveals itself as a diatribe against MTV and all the bands who embraced it (“Seen your video/ Your phony rock ’n’ roll/ We don’t want to know”), a hobbyhorse the ’Mats would continue to flog in hysterical fashion on their next album as well. (In keeping with the anxiety-of-adulthood theme, Jesperson notes that the song was originally titled “Adult”—“You look like an adult/ You act like an adult/ Who taught you that?”)

If Let It Be is the sound of a rock band dragging itself kicking and screaming into maturity, then from today’s vantage point, the LP’s broader historical context makes this quality resonate in unexpected ways. In the 21st century, much ink has been spilled over rock’s gradual decline, at least in terms of its onetime centrality to the popular-music firmament. 1984 was one of those great hinge years in popular-music history, like 1967 or 1977 before it. Rock, widely understood since the late 1960s as music made mostly by white men, was still a massive cultural force—Born in the U.S.A. came out that year, after all—but you didn’t have to squint to see some cracks in the genre’s monolith. 1984 was the year Whitney Houston debuted and Madonna released “Like a Virgin,” while Michael Jackson’s record-breaking Thriller and Prince’s Purple Rain soundtrack dominated the Billboard album charts, holding the No. 1 spot for a jaw-dropping 37 weeks between them. And of course a burgeoning musical form was continuing to ascend out of New York City: In 1984, Run-D.M.C. released its self-titled debut, to critical acclaim and surprisingly robust sales; a 16-year-old who called himself LL Cool J released his first single; and T La Rock & Jazzy Jay’s “It’s Yours” became the inaugural release of a small label called Def Jam. Forty-plus years after its release, Let It Be still sounds like a great rock album, and one that seems to intuit that something might be gaining on it.

Get the best of movies, TV, books, music, and more.