In 1971, a 13-year-old boy appeared briefly, silently, in a film that would later be nominated for four Academy Awards. That flicker of screen time, now mostly forgotten, marked the on-camera debut of Daniel Day-Lewis, an actor who would become the only man in history to win the Academy Award for Best Actor three times.

His career was never prolific—less than 35 films over five decades—but it was exacting, even punishing. Performances in My Left Foot, Lincoln, and There Will Be Blood (2007) didn’t just earn praise. They reshaped the art form. He built canoes for The Last of the Mohicans and refused to break character during My Left Foot, remaining in a wheelchair even off-camera. No stunt. No press. Just immersion.

Daniel Day Lewis In There Will Be Blood. © 2007 Paramount HE

Daniel Day Lewis In There Will Be Blood. © 2007 Paramount HE

In 2017, after completing Phantom Thread, Day-Lewis announced his retirement from acting. In a rare interview with WMMagazine, he described feeling “compelled to stop,” explaining that the work no longer gave him the satisfaction it once had.

Seven years later, he’s back. And this time, the performance isn’t just about him.

Anemone and the Fragile Weight of Legacy

Day-Lewis returns in Anemone, a modest British drama released by Focus Features, co-written by him and directed by his son, Ronan Day-Lewis. The film follows a man who sets off into the forests of northern England to reconnect with his estranged brother. Slow, sparse, and deeply introspective, the story unfolds more through tone than action.

The film’s IMDb page lists a runtime of 125 minutes and a modest critical reception: 5.7 out of 10 based on over 4,500 user reviews, alongside a Metascore of 53. Despite visually rich cinematography and a brooding score, reactions have skewed mixed.

Some critics described the pacing as deliberate; others called it aimless. One reviewer praised the “auditory and visual restraint,” while another noted it “collapses under the weight of its own pretensions.”

Sean Bean and Daniel Day-Lewis in Anemone. © 2025 FOCUS FEATURES LLC

Sean Bean and Daniel Day-Lewis in Anemone. © 2025 FOCUS FEATURES LLC

Day-Lewis, unsurprisingly, is the exception. His performance as Ray—a quiet man racked by emotional inheritance—has been called “disarmingly restrained.” He delivers grief, memory, and moral ambiguity not through monologue, but through pauses, gestures, and subtle shifts in expression. It’s the kind of work only a few actors are even capable of attempting.

But the question hovering over Anemone isn’t whether Daniel Day-Lewis is still great. It’s whether his greatness still fits into this era of filmmaking.

Nepotism, Craft, and the Directorial Learning Curve

Ronan Day-Lewis, the director and co-writer, is a former painter, and it shows. The film’s palette is rich. Its compositions are often gorgeous. But critics have pointed to gaps in pacing, narrative cohesion, and emotional payoff.

Several reviewers noted an overreliance on stylized silence and thematic suggestion, without the storytelling clarity to support it. “Just because you’re someone’s son,” one reviewer commented, “doesn’t mean you know where the camera belongs.”

Daniel Day Lewis, Jennifer Lawrence, Anne Hathaway & Christoph Waltz at the 85th Academy Awards at the Dolby Theatre, Los Angeles. Credit: Shutterstock

Daniel Day Lewis, Jennifer Lawrence, Anne Hathaway & Christoph Waltz at the 85th Academy Awards at the Dolby Theatre, Los Angeles. Credit: Shutterstock

The accusations of creative nepotism are hard to ignore, especially when the result feels like a high-profile workshop rather than a fully realized debut. And yet, others argue that for a first feature, Anemone is not without merit. Its use of space and stillness has drawn comparisons to early works by Lynne Ramsay and Andrew Haigh, directors whose quiet films grew more powerful in hindsight.

Still, it’s unclear if the project would have reached the public eye at all without Day-Lewis senior attached—an uncomfortable reality in an industry increasingly scrutinizing who gets to create and why.

Can Greatness Be Preserved in a Slower Cinema?

In his final major role before retirement, Day-Lewis played Reynolds Woodcock in Phantom Thread, a character whose artistic precision became his own undoing. It now reads like prophecy.

His return in Anemone doesn’t feel like a comeback or a curtain call. It feels like an unresolved note—a question rather than a conclusion. Has the film culture changed too much in seven years for this kind of cinema to grow again?

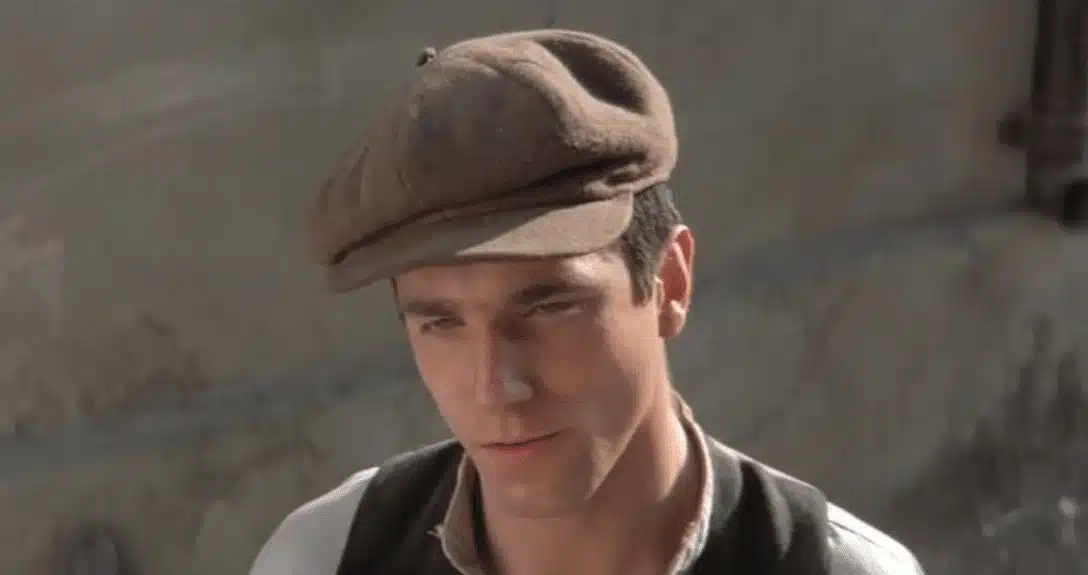

Daniel Day Lewis As Colin in Gandhi (1982).

Daniel Day Lewis As Colin in Gandhi (1982).

The late-2000s prestige film era that Day-Lewis helped define—anchored by performance-first films like There Will Be Blood—has since been eclipsed by streaming-driven, high-volume content cycles. Fewer directors are asking actors to disappear into roles for six months. And fewer actors seem interested in that bargain.

Still, Day-Lewis remains singular: a master craftsman uninterested in volume, attention, or brand. Whether or not Anemone succeeds on conventional terms may miss the point. What it shows is that the art still matters to him—enough to risk returning, not with a studio spectacle, but a quiet collaboration with his son.