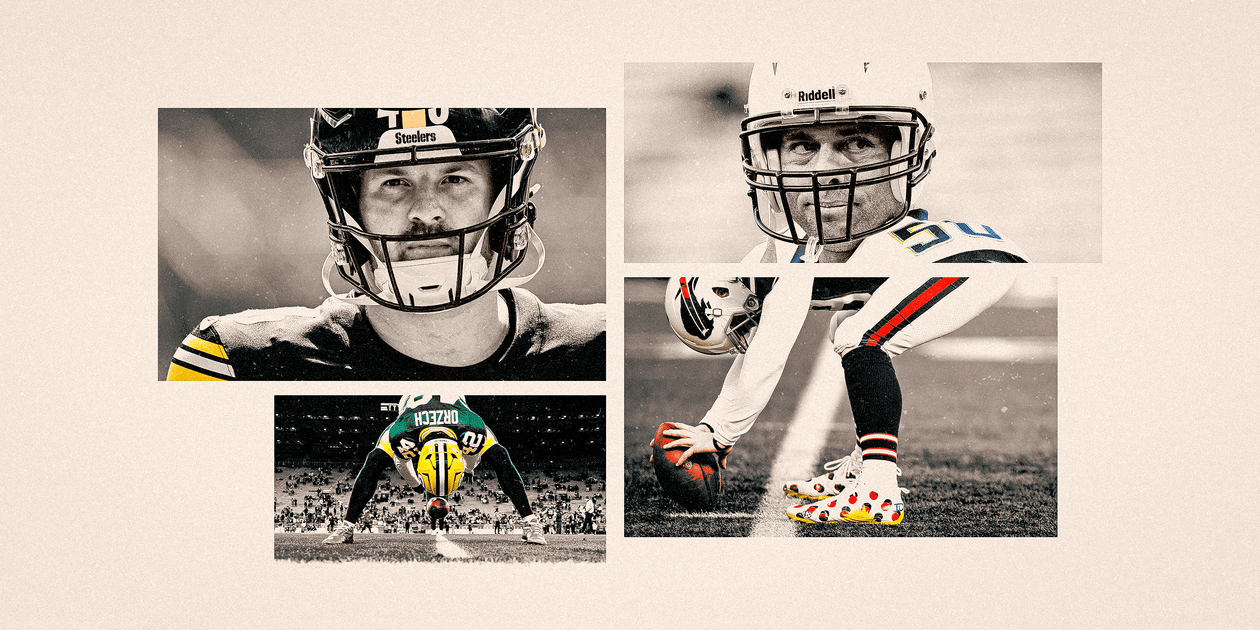

Behold the long snapper, the last happy man in football, in his place.

Across the Pittsburgh Steelers’ locker room, a future Hall of Fame quarterback stands somewhere inside an eyewall of cameras and recorders and expectant gazes, talking about a game against his former team. Over here, on this side of the space, at a corner stall next to the showers, Christian Kuntz has thoughts on a bad loss for Chartiers Valley High School football.

It’s two straight, actually. But Kuntz reminds anyone who cares to listen that the point is to get healthy and primed for the state playoffs. He already bought a spaghetti dinner for the lads at his alma mater in the South Hills. He’s gotta figure out the next nice thing to do. Speaking of food, though, you got DiAnoia’s in the Strip District for real good Italian. Or Alla Famiglia, up on Warrington Avenue. Fire spot. Used to park cars there, Kuntz notes. There’s also Napa Prime for steak. Umi, in Shadyside? Great sushi. Should still be perfect for a date night once it replaces Mr. Shu, the executive chef who just retired, and reopens.

“Expensive, but these guys can afford it,” Kuntz says, nodding in the direction of, well, everyone. “I got recommendations for days.”

He could go on, yes. They all know he could go on.

“The Prince of Pittsburgh,” linebacker Nick Herbig chirps.

It’s a stinger; Kuntz, born in suburban Scott Township and still not far away at age 31, allegedly has referred to himself as such. Linebacker Cole Holcomb wonders if highlights from Kuntz’s playing days at Duquesne, where he set the school’s career sacks record, are on Hudl. A few minutes later, a passing teammate spies Kuntz, of all people, holding court while Aaron Rodgers, of all people, does the same. The juxtaposition is not overlooked.

“Best long snapper ever! The G.O.A.T. long snapper!”

Kuntz smiles. “See the s— I gotta deal with?” he says.

So go the glory days in an upside-down world, a plane of existence inhabited by no one else in the NFL.

To be a professional long snapper is to have your worth measured by maybe a half-dozen plays every week. A pass-fail exam each time for a brotherhood of perfectionists. But the job is also a quest. Do it well enough, and there is stability and longevity in a game not noted for either. There is general health, or better odds for it. There are multimillion-dollar contracts that buy a lot of freedom when you’re done. So maybe you get a beer named after you, or maybe you close a Tony Robbins seminar at midnight, or maybe you just drop your kid at school and hit golf balls in paradise.

At a position more or less immune to the bloodthirst of the sport — to the idea of earning a living by inflicting pain — a snapping career can be a rapture. Thirty-two lightning bolts waiting for a bottle. “We’re always working to be better so we can stay and hang out with the cool kids,” says Tennessee Titans snapper Morgan Cox, now in his 16th season. “The joke has always been that we’re all the same guy, basically. We’re just fired up to be out here.”

Show up, work hard. Sling a ball through your legs. Lastly — in the not-so-refined words of the Prince of Pittsburgh — don’t be an a–hole.

And, lo, the gates swing open to football nirvana.

“I tell people,” says Kuntz, who traded hunting quarterbacks for spinning footballs, “my life’s not real.”

In the 32-year history of the NFL Special Teams Player of the Week award, only one long snapper has won. Cole Kmet of the Chicago Bears took home the honors after a win over the Jacksonville Jaguars in October of 2024, which was remarkable for a couple of reasons: Kmet also caught two touchdown passes in the game, and he is not actually a long snapper. He’s a 6-foot-6, 257-pound tight end with 274 career catches in that role. But regular snapper Scott Daly hurt his knee in the first quarter of that midseason game in London. Kmet filled in. A moment in NFL history followed.

The Bears created a reflective collage to commemorate the award and presented it to Kmet. He thinks it’s somewhere in his basement.

“That was an awesome job by Cole,” Daly says, laughing at his Halas Hall locker stall, “but I think he also ruined it for long snappers after that.”

Beyond the self-deprecation — seems it was a collectively transcendent moment when EA Sports put long snappers into its “Madden 26” video game — lies the truth that the job matters. The most common margin of victory in NFL regular-season games for the past quarter century? Three points. A reliable kicking operation, especially given the increasingly superpowered legs of the kickers themselves, is a weapon. A faulty one opens black holes.

So these men take the trade seriously. “I don’t know if people understand how much of an art snapping is, and how much detail goes into it,” Buffalo Bills snapper Reid Ferguson says. They work by the fraction of an inch. Aim small, miss small, and hit your spot, is how a college coach long ago explained it to former Bears snapper Patrick Mannelly, who put his name on an award annually given to the nation’s best college player at the position. On field goal attempts, the laces must hit the holder’s hands such that he simply puts the ball down before the kick. What looks like a fine effort might turn a snapper salty for a week. And never mind the catastrophe of an actual bad snap.

“It’s like you’re a professional dart thrower and you’ve got seven plays a game,” says Clint Gresham, the snapper for the Seattle Seahawks’ Super Bowl XLVIII winners. “And if one of them is not perfect, then you’re kind of a failure.”

Thanks to a rule change in 2006, teams cannot set rushers up directly over the long snapper. It’s better, but only incrementally so: The metahumans to block are now less than a foot to the right and left. Imagine hunching over, throwing a ball perfectly and then contending with, say, former No. 1 overall pick and All-Pro linebacker Mario Williams in the A-gap. “I felt like he slapped me in the head twice before I even realized the play was happening,” says Cox, a five-time Pro Bowler.

“Everyone watches us Monday through Saturday and goes, ‘That looks like an easy job,’” says J.J. Jansen, who holds the Carolina Panthers career record for most games played, at 271 and counting. “Because Monday through Saturday, it is. But on Sunday at 4:15 p.m., when you gotta hit a game-winning field goal, everyone’s on the sideline praying.”

Still, the line at the door keeps getting longer.

That a line exists, at all, isn’t new. The list of participants at long snapping guru Chris Rubio’s camps who then went on to play in college dates back two decades. What’s wild is the current starting point. San Francisco 49ers snapper Jon Weeks first attended the Rubio camp in 2004, out of high school. By the time he was a senior at Baylor, revisiting as a counselor, morning sessions began with attendees in sixth grade. Ferguson remembers coaching a fourth-grader at the camp. And that fourth-grader, Quentin Skinner, went on to snap at LSU and Troy.

“It’s something that opens doors,” Weeks says. “Parents have realized, at least at the college level, you don’t have to be this 6-foot-3 monster to get your school paid for and play football.”

The depth of training is certainly an evolution from a Duke assistant coach telling Mannelly to hone the craft by hitting a goal post, stripped of padding, 10 times in a row after practice. This is more like building bent-over androids. “I’m addicted to snapping,” says Chris Stoll, who won the Mannelly Award in 2022 and signed a three-year contract with the Seahawks out of Penn State. “We can get so much better by just moving your thumb position or, like, keeping your weight on your insteps more.”

The math is daunting: hundreds of college spots bottlenecking into 32 NFL jobs. It doesn’t stop anyone from trying to squeeze through, given what’s on the other side.

A long snapper’s value, in short, is not being a problem. In one interpretation, that is tending to business and being a good dude. Maybe shoot a Notes file to newcomers with restaurant recommendations, like Ferguson does. Or be a walking Zillow like Kuntz, when guys ask about good neighborhoods to live in. Maybe provide a sounding board for men going through men stuff, like former Philadelphia Eagles snapper Jon Dorenbos. “I would help problem-solve,” Dorenbos says now. “I was a locker room guy, and I got with a coach (Andy Reid) who valued that.”

Disaster prevention and peace of mind, though, are mostly what the money is for. Scoring in the NFL in 2025 is tied for the second-highest rate ever. Every point is immense. Thus, per Over the Cap, 15 long snappers are signed for more than $1 million guaranteed. “You don’t realize how important they are until you don’t got one,” says longtime Steelers special teams coach Danny Smith. It’s not avant-garde personnel management; multiyear contracts for snappers date back decades. The outlay is minimal in a sport featuring 23 players with more than $100 million in guarantees. But it’s a reasonable price for one less thing to worry about.

“If I was the (coach) at the podium, it’s something I would never want to be thinking about,” Packers kicker Brandon McManus says. “When you feel like you have someone and you’re comfortable and can turn a blind eye to it, it’s a great feeling.”

This golden ratio of trust and money, both hard-earned, creates enviable stability. “Most NFL players and most athletes in general have access to a ton of money, a ton of fame,“ Jansen says, “but they’re sort of nomads.” An NFL long snapper career, on average, lasts 7.5 years. The rate for all other positions is less than half that. How refreshing, in a game where tenure can be a punch line, to establish roots. To make a plan. Jansen has lived in three houses in one city while buying a small stake in the AHL Charlotte Checkers. Ferguson, who signed a four-year, $6.5 million extension in March, has invested in a restaurant and a soccer franchise in Buffalo. No, it is not the $250 million in guarantees Josh Allen received to quarterback the Bills, but any apples-to-apples comparison sort of misses the point.

At 31, the team’s most anonymous player already has steady footing for decades. “Whenever it does end, we’ve provided ourselves enough financial security to where I don’t immediately have to look for a job to support the family,” Ferguson says. “Honestly, it’s the best.”

Even when NFL realities upend everything, it might not matter. When Cox lost his job with the Ravens in 2021, he landed with the franchise 200 miles from his hometown of Collierville, Tenn., where he planned to settle down anyway. “‘Dream’ doesn’t even feel like it does it justice,” he says.

That’s the ticket. Sheer accrual of tree rings, anywhere. It begets freedom. Mannelly snapped for 16 seasons, does some radio and collaborated on a beer. Jon Dorenbos lasted 14 seasons, finished third on “America’s Got Talent” while playing for the Eagles and parlayed football, his personal story and sorcery with a deck of cards into a career that whips him around the globe. Gresham wrote a book titled “Becoming” that built some momentum on Amazon … before Michelle Obama released a memoir with the same title.

Do the job well, you do what you want after. Or not much at all. “I’d say that’s a pretty good option, right?” says Josh Harris, who logged a decade with the Atlanta Falcons and then signed a four-year, $5.6 million deal with the Los Angeles Chargers. “If you’re able to play long enough and you’re smart enough with what you earn along the way, that’s definitely something that you could do on the back end of it. Hey, I love to play golf. So I see a lot of golf in my future.”

Of course there’s a crowd gathering for that. But no one is in a hurry to make room. The Minnesota Vikings’ Andrew DePaola is 38, and over the last three seasons he’s twice been a first-team All-Pro while becoming the first long snapper to make three straight Pro Bowls. Jansen overhauled his workouts at 34 — “I did more explosive movements in the last five years than I did my whole life,” he says — and began velocity training. He then beat out a Mannelly Award winner, Alabama’s Thomas Fletcher, the Panthers drafted to replace him. Jon Weeks, also a spry 39, started hot-needle treatments because, as he puts it, he’s “gonna do it till they tell me I can’t do it anymore.”

Everyone wants in on the party. Cool. Those inside understand the trick is not getting kicked out.

“Thirty-two jobs in the world,” Christian Kuntz says. “People think it’s impossible to get in. It’s damn near impossible to stay in.”

There always will be a Scott Daly. Three-year starter at Notre Dame, perfect on 253 snaps as a junior and a senior, and no way in. He does not play in the NFL for four seasons. Two springtime professional leagues fold while he’s in them. He gives himself one calendar year. If there’s no call, it’s on to financial advising. Eleven months later, the Detroit Lions call. He takes the job from a 17-year veteran. He loses it to a rookie three years hence. He joins the Bears’ practice squad in preseason 2024, and the starter hurts his back two weeks later.

Daly now has 21 straight starts for the franchise he grew up on in Chicago’s northern suburbs. The Bears blocked a field-goal attempt to win a Week 4 game against the Las Vegas Raiders after Daly scouted a tell in the other snapper’s delivery. No, he won’t dare buy a house yet. “It’s surreal,” Daly says. “To be able to come back here was part of my journey that I didn’t think was possible.”

There always will be a Rick Lovato, too. First player from Old Dominion to appear in the NFL. Bounces between three teams before landing with the Eagles in 2016, replacing Dorenbos, who broke his wrist on the play that tied the franchise’s record for consecutive appearances. Wins two Super Bowls. But he’s cut after that second title. “That’s the life of a snapper,” he says. When Josh Harris hits the injured list this preseason, the Chargers bring Lovato aboard. He sublets a house in Redondo Beach. He knows he’s not replacing Harris. He’s only trying to show he can still be the guy, for someone.

“I may not be able to decide when I can hang it up,” Lovato says in early October. “But maybe I can.”

Eleven minutes after the trade deadline passes on Nov. 4, the Chargers make an announcement. They’ve placed Rick Lovato, 33, on the reserved/retired list.

Harris is healthy. There can only be one. Sometimes the end of the quest is a drive off the cliff.

And, sometimes, it’s heaven in a burger and beer on a San Diego afternoon.

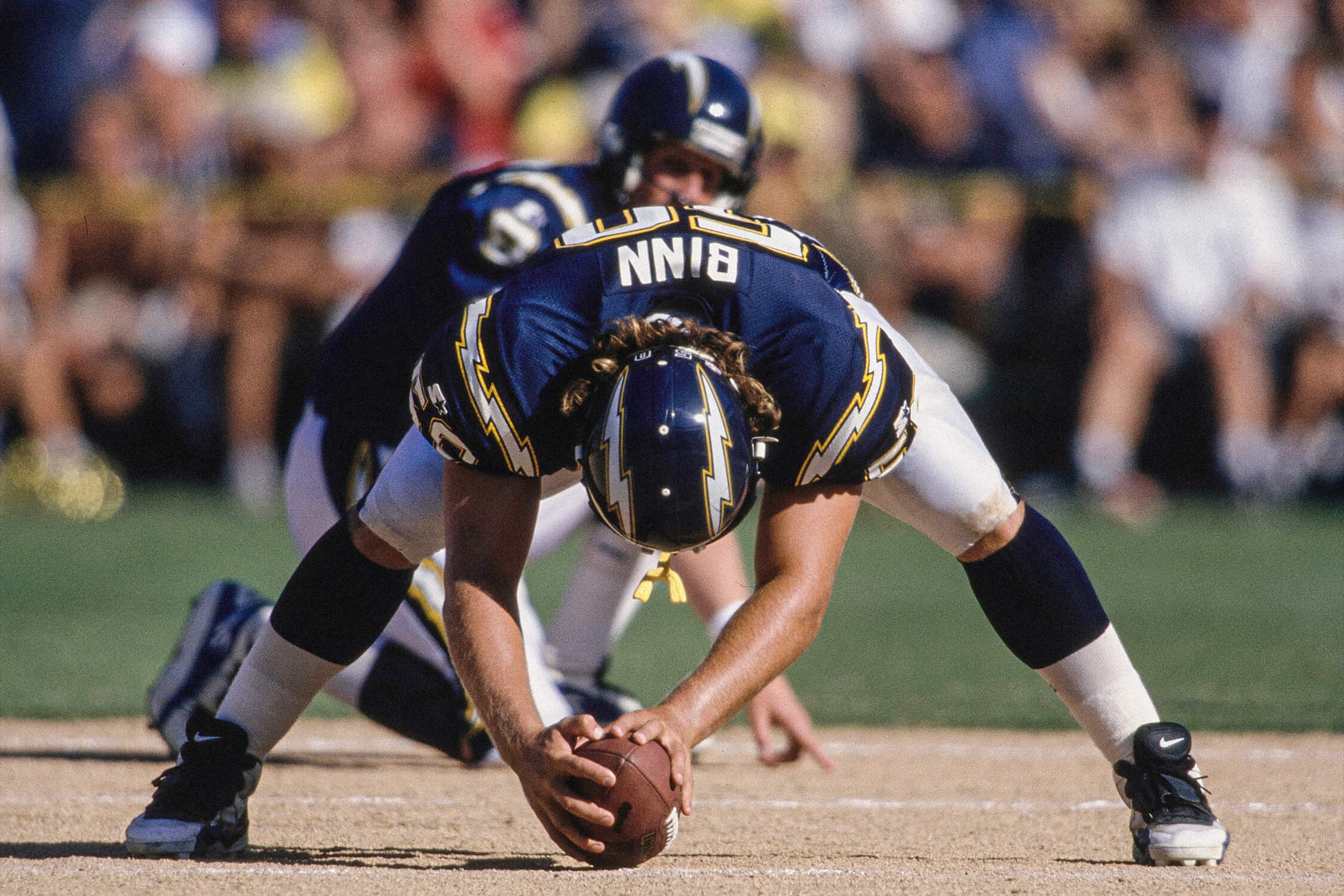

“Oh, yeah,” Morgan Cox says. “We all knew who David Binn was, I can tell you that.”

Rocky’s Crown Pub opened its doors in 1977, and it’s as if the rest of the world filled in while it stayed right there.

Multiple flat-screen televisions and a natty Russian River Brewing IPA on draft somewhat betray the bit. Otherwise, memorabilia on wood-paneled walls ranges from a faded Junior Seau Celebrity Golf Classic poster to a surfboard to musty photos of arcane ex-NFL players inside the door off Ingraham Street. Behind the bar hangs a menu: a hamburger (in two sizes) and a cheeseburger (also in two sizes), plus fries. Thus ends the menu. Food comes in red plastic baskets. Only lately did Rocky’s start taking credit cards.

Around 1 p.m. on a Tuesday in Pacific Beach, the place hops. In walks a rangy guy who looks like he belongs, both here and to an era. Longish hair escaping beneath the back of his trucker hat, peppery scruff on his cheeks and chin, wearing a black Chevy Camaro T-shirt and shorts.

This is Dave Binn — Chargers long snapper for 17 years, husband and father of two, patron saint — fresh from the driving range and a workout.

“Binn Man!”

The greeting comes from Kris Dielman, a Chargers teammate once upon a time. They both live nearby — Binn has been in the same house since 1998, up on the south slope of Mount Soledad — and their kids go to the same high school. Hard to tell if it’s coincidence they’re both at Rocky’s for weekday lunch or if that’s an even-money bet. After a handshake and small talk, Binn orders a cheeseburger and a Blind Pig IPA and leads the way to a high-top table on the patio.

Sun’s out. Temperatures in the 70s. No reason to wonder what another life might be like.

“I mean, I had ideas,” Binn says. “I did a big trip in Costa Rica. I was like, ‘Dude, we could live off the land here, could open a little bar at the beach.’ There’s f—— mangoes hanging out on the trees. Surfing. You could get an acre on the beach for like 50 grand back then. That was a thought.”

He never played quarterback at San Mateo (Calif.) High School like he hoped. He got the long snapper job as a freshman, and it eventually got him a preferred walk-on spot at the University of California. In his second-ever college game, Binn snapped an extra point against Miami (Fla.), picked his head up and got blasted by Russell Maryland. By midseason, though, he was handling punt snaps, too. He discovered he’d been put on scholarship when he collected books for spring semester and asked the woman at the window for athletes if his name was on one of the cards in her box. After some shuffling, she replied: Here you are!

“I just rolled from there,” Binn says.

When NFL scouts and coaches passed through, Binn introduced himself. Asked if they might need a snapper. The offensive line coach for the Chargers gave him a look, which precipitated a return visit from the special teams coach. “He had me do 10 or 15 punt snaps,” Binn recalls, “and every one was dead in the nuts, like perfect.” Around 9 a.m. on the day after the 1994 NFL Draft, a roommate told him the Chargers were calling. Guy named Bobby Beathard. Binn didn’t know who that was. Plus, he was still sleeping. Binn told his buddy to take a message.

Apparently, the Hall of Fame general manager took no umbrage, because Beathard handed Binn a deal for the rookie minimum of $108,000. He threw in a $2,000 signing bonus. Which was awesome, since Binn was still a college senior about $1,500 in the red. “So that’s how I got down here,” he says. “That’s how it started.”

The rest is a symphony.

He vaguely recalls a movie playing on the bus ride up to Los Angeles to play the Raiders at the Coliseum — maybe “Shaft,” maybe “Dolemite” — but definitely remembers thinking it was an absolute trip that he’d made an NFL team. Same with listening to Stan Brock, a big old tackle near the end of his rope, talk about guys smoking cigarettes in the locker room in the early 1980s. And trying to tackle ciphers like returners Devin Hester and Brian Mitchell. “For me,” Binn says, “that was fun.” And going out after a big win and seeing half the team at The Tavern or The Beachcomber. And standing on the field before Super Bowl XXIX, talking with a couple former Cal teammates, wondering how in the world they got here, and one of them calling out to the 49ers’ quarterback to come say hello. This is how Dave Binn met Steve Young.

Binn settled into that house in Pacific Beach. He started earning real money on the back end, even getting half a million dollars up front on a five-year contract. Wound up as the Chargers’ career-leader in games played with 256 appearances.

Somewhere in there, he got invited to a charity golf tournament in Canada and flew out on a 737 with Cheech Marin and Bruce Greenwood, among others. Binn and a buddy were headed to their rooms to freshen up for the afterparty when they saw a couple women walking toward the elevator. They held the door. “You guys hockey players?” Pamela Anderson asked them after stepping inside. After explaining that he played football and continuing the conversation at the festivities that night, Dave Binn dated the star of “Baywatch” for a couple years. (His wife, Jennifer, it’s worth noting, still busts his chops about it.)

“All because I threw a ball between my legs,” he says, on the other side of disbelief. Now he lives by the ocean and decides to take the dogs for a run, or not.

Valhalla in real life.

Dave Binn takes a bite of his cheeseburger.

“It’s a good gig,” he says. “But I never looked at it that way. I think that’s probably why I had the run I did. I thought I was going to get cut every year. Or even week to week. You walk by the general manager’s office, and there’s this big whiteboard. There’s kind of the depth chart of the guys on the team. And then the names on the side. There’s like two or three snappers there that are good. But they’re not on a team. And I know those names.”

The only way up is to understand how far it is down, and how fast the bottom hits.

A forever blessing and affliction for his kind. Even the ones already enjoying the breeze.

“From the outside looking in, it was kind of a pipe dream, right?” Matt Orzech says in a room off Lambeau Field’s auditorium, outfitted in a Green Bay Packers hoodie and sweatpants, outlier and archetype all at once.

After moving from suburban Milwaukee to southern California for high school, Orzech went to Division II Azusa Pacific University to play tight end and pitch. He became a long snapper because the starter got hurt and the football coach figured Orzech knew how to throw something over and over again. He went to a predraft showcase with no idea how good or bad he was. By chance, Orzech’s first NFL stop was Baltimore, where a veteran named Morgan Cox assured him he had the goods. So he kept chasing.

Green Bay is his sixth stop. It could be the last. In a league gravitating to athletic snappers for blocking purposes, Orzech is a 6-foot-3, 245-pound former collegiate position player with the best grip strength on the roster. “He’s like a bear,” Packers punter Daniel Whelan says. “Probably helps having three kids. Dad strength.”

In August, Orzech became the NFL’s third-highest paid long snapper. Three-year, $4.8 million contract, with a $300,000 signing bonus. “It’s nuts,” he admits. But it’s his. And, here, it can last, depending on your definition of perfection. “That was kind of the narrative I was told — that you could do (long snapping) for a really long time,” Orzech says. “And if you do it well and are good at it, you can last as long as you want.”

There are more famous, more well-compensated players. But they often live football lives under clouds, with hastened expiration dates. The long snapper, and his version of happiness, endures. It’s worth the pursuit. That’s why more and more pursue it. And why the fortunate few hang on as long as they can.

Orzech did not splurge after signing his new deal. There’s always the chance the next rung on the ladder is greased. But Destiny Orzech strung up balloons and ordered a cake. Her instructions were simple: The cake was meant to commemorate Year 7 for her husband in the NFL.

They opened the box, and the universe winked back.

You’re 7!, the cake read.

It was fine. Cake is cake. The next time Orzech will celebrate is when he reaches a decade in the NFL, and life is all icing then. Nothing is ever guaranteed. But he can see it from here.