Nunavik hunters are being asked to delay the fall beluga harvest, as the number of whales in one beluga population is estimated to be at a record low.

Fisheries and Oceans Canada’s (DFO) survey estimate for the Belcher Islands-Eastern Hudson Bay beluga population in 2024 was 2,200 animals – the lowest estimate on record.

The Nunavik Marine Region Wildlife Board’s (NMRWB) 2021-2026 management plan has an objective to ensure there’s at least a 50 per cent chance the Belcher Islands-Eastern Hudson Bay stock can be maintained at 3,400 after five years.

However, DFO says that the survey estimates used in 2021 to set that objective are now outdated, and the 2024 survey results are more accurate. The new data suggest the population has declined around two-and-a-half to three per cent each year since 2015, and more since 2021. DFO no longer believes the 3,400 target can be met, and that the population could become quasi-extinct by 2037.

The NMRWB is now encouraging hunters to shift the harvest to later in November. Executive director Tommy Palliser said Eastern Hudson Bay belugas generally migrate earlier in the fall, whereas the Western Hudson Bay population – which has seen healthy numbers since 1987 – migrates later.

Delaying the harvest, he said, would mean more Western Hudson Bay belugas are caught, as opposed to the Eastern Hudson Bay Beluga.

“It is our responsibility and duty to make sure that the hunters and the Inuit understand this and look at it as a potential opportunity to meet their community needs in terms of harvest, but also help in the conservation efforts of the Eastern Hudson Bay beluga,” he said.

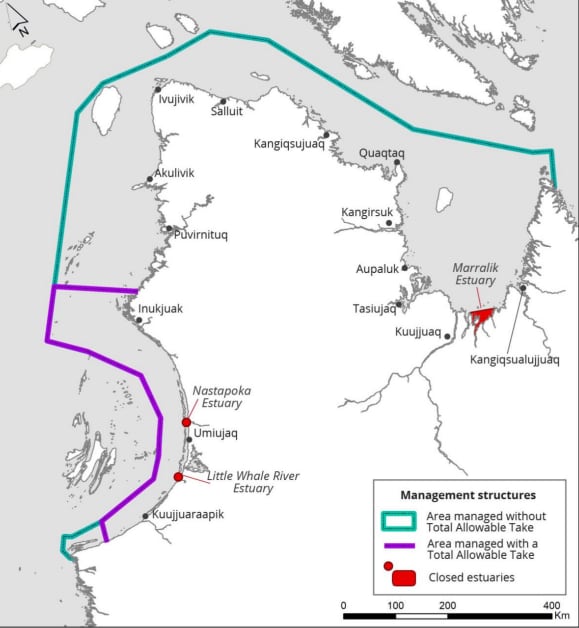

He also worries about safety with the quota system. There is a total allowable take (TAT) of 20 belugas in the Eastern Hudson Bay Arc region, which is in the waters closest to the villages of Inukjuaq, Kuujjuarapik and Umiujaq.

A map which outlines the area with a total allowable take of belugas in the Nunavik Marine Region. (Department of Fisheries and Oceans Canada)

A map which outlines the area with a total allowable take of belugas in the Nunavik Marine Region. (Department of Fisheries and Oceans Canada)

But in a document outlining reasons to reconsider the boundary of the TAT, NMRWB states the quota system can put hunters at risk. Over the past three decades, NMRWB said there were two fatalities among hunters from Inukjuak who travelled beyond the boundary for harvest.

“Under the current TAT system hunters must make long-distance hunting trips which are dangerous and costly, leading to meat spoilage and wastage while trying to transport harvested beluga meat home,” the document reads.

Quotas were a ‘game changer’

Umiujaq’s Peter Tookalook still remembers when the Eastern Hudson Bay belugas began to gradually disappear from the area – especially in the nearby Nastapoka River.

“The belugas were, in the early ’80s in the Nastapoka River, about 300 to 1,000 per pod every time we went there. But gradually, during the late ’80s, they were disappearing since the over-hunt,” he said.

Nowadays, he said he sees roughly a dozen in the Nastapoka River, which alongside the Little Whale River, has been closed for harvest since 2001.

DFO’s survey report states that “commercial harvests in the 19th Century initiated the depletion of beluga in eastern Hudson Bay. Subsequent subsistence harvests may have limited recovery.”

That triggered the quotas, which Tookalook called a “game changer,” and a necessary one. He recalled the difference it made at harvest time.

“We had to rush, we had to make sure that we were part of the family that gets our beluga yearly,” he said.

“If we don’t put any quotas, [other hunters] will get one to 300 belugas on their own, for sure.”

But not everyone agreed with the quota system.

Tommy Palliser, of the NMRWB, said the sort of finger-pointing he saw when it was first introduced goes against the Inuit way of doing things.

“This quota system put Inuit against DFO, and then Inuit against Inuit, which was sometimes very ugly to watch,” he said.

Tommy Palliser of the Nunavik Marine Region Wildlife Board said there are conflicting views between Inuit elders and DFO’s research, about how how belugas behave. (Sarah Leavitt/CBC)

Tommy Palliser of the Nunavik Marine Region Wildlife Board said there are conflicting views between Inuit elders and DFO’s research, about how how belugas behave. (Sarah Leavitt/CBC)

Palliser says that’s why he’s striving for an Inuit-led solution.

“We continue to work on these issues that Inuit can lead and not have so much of a top-down approach to management, which involves quotas, but more of a bottom-up approach.”

Industrial impacts unclear

As the head of the wildlife board, Palliser finds it challenging to balance DFO’s research with Inuit knowledge. For example, belugas are known by Inuit to roam over vast areas, rather than stay in one part of the ocean.

“They go wherever their food sources are. Whereas DFO’s [approach] is more of a rigid look on… where it’s specifically,” he said.

He also takes issue with what he views as a lack of research on the industrial impacts on Eastern Hudson Bay beluga habitat. Palliser said he and others in Inukjuak have watched nearby river levels go down, and he wonders if that’s related to climate change, or to Hydro-Québec’s operations upstream. He hasn’t seen any DFO research on this.

“When we used to go to the Nastapoka River, we used to be able to see the mist of the river miles away and a big cloud just over it, but now we don’t see that, and we have to be really close,” he said.

Peter Tookalook of Umiujaq said he has seen beluga numbers in the Nastapoka River plummet since the 1980s. (Bartley Kives/CBC)

Peter Tookalook of Umiujaq said he has seen beluga numbers in the Nastapoka River plummet since the 1980s. (Bartley Kives/CBC)

“As a biologist, I would be embarrassed, to be honest. I mean, if you’re understanding the beluga so much and you don’t study their habitat and the impacts to it, then it’s a biased system… it’s conveniently pointing the finger at Inuit which I don’t think is right in any way.”

But DFO biologist Caroline Sauvé said surveys in the area only began in the 1980s, after the La Grande hydroelectric project was built. That means they don’t have data to do before-and-after comparisons of the impact it could have on belugas.

She said DFO’s research also does account for the potential impacts the loss of sea ice could have on belugas, such as making them more vulnerable to killer whales, but there aren’t specific numbers on that yet.

“There is currently not sufficient information on the predation levels of the killer whales on the beluga to actually estimate what this predation would contribute to the stock mortality. So it’s really hard to quantify,” she said.

However, DFO said that’s something it’s open to exploring.

“DFO is open to working with co-management partners and community members on research projects to improve our understanding of the impacts of a changing environment on Eastern Hudson Bay beluga,” the department said in a statement.

The NMRWB is now asking to extend its beluga management plan by a year, to end on Jan. 31, 2027. Palliser said that’s so they can gather more up-to-date information and relay that to Nunavimmiut.

Extending the plan requires the DFO minister’s approval. The department said it cannot provide comment on those discussions until a final decision has been made.