As Gary Ellis lay dying in August 2023, no one at the facility caring for him called his son.

Instead, staffers called Ellis’ court-appointed state guardian, who had recently taken charge of all decisions related to the 69-year-old man’s care. Not until it was too late did Gary Brown learn his father had been at death’s door, Brown told the Tribune.

“When I went there the nurse was like, ‘We’ve been trying to call someone all night but nobody answered the phone,’” Brown said. “All I got was ‘I’m sorry.’ ‘I’m sorry’ didn’t do nothing to help me or my dad.”

The scenario was exactly what Brown feared when he learned, to his surprise, that Northwestern Memorial Hospital had moved to appoint a guardian for his father. The family said Northwestern had been treating the retired CTA bus driver for months, except for a brief stint at a rehabilitation facility, after he suffered a fall in April 2023.

Ellis’ family told the Tribune that by mid-May the hospital began pressuring them to approve a transfer to a nursing facility, saying his insurance coverage had stopped. Brown said he was still trying to navigate his best option when a judge signed off on the temporary guardianship petition, taking away Brown’s ability to decide anything on his father’s behalf.

Putting someone under guardianship has profound consequences, often stripping the individual of the right to make personal, medical and financial decisions for the rest of their lives. Courts, government officials and advocates for adults with disabilities say it should be an option of last resort, used only when people cannot make their own decisions and no less restrictive solution is available.

Gary Brown holds a memorial card honoring his father, Gary Ellis, who died under guardianship after a hospitalization. (Eileen T. Meslar/Chicago Tribune)

Gary Brown holds a memorial card honoring his father, Gary Ellis, who died under guardianship after a hospitalization. (Eileen T. Meslar/Chicago Tribune)

Yet Chicago-area hospitals recently initiated hundreds of guardianship petitions in just 18 months, a Tribune investigation has found, sometimes to the dismay of family members or friends who did not want people they loved to be placed under someone else’s control.

In many cases, guardianship eased the way for hospitals to discharge patients to subpar nursing homes, sometimes bypassing family members who disagreed with the hospital’s choice or were slow to make other arrangements.

Many relatives or friends wound up battling on their loved ones’ behalf long after the hospital had solved one of its immediate problems — a patient it wanted to discharge.

Some hospitals moved for guardianship over the objections of patients who later successfully fought to regain their freedom, or in cases where the patient’s rapid subsequent improvement raised questions about the need for such drastic measures.

Coming next: The business of private guardianships.

In cases where patients have little money, hospitals often seek to place them with the publicly funded Office of State Guardian at the hospitals’ expense. But if the patient does have assets, the Tribune found, the hospitals and their hired lawyers almost always recommend a certain private care management organization as guardian. That opens a pipeline to the patient’s life savings, which can be rapidly drained to pay for the care they receive as well as fees charged by the private guardian and the lawyers working on the case.

The consequences of guardianship can be so severe and long-lasting that some hospitals, even those that serve many low-income patients, told the Tribune they try hard to avoid it.

Yet two of the area’s largest and most prestigious medical institutions, the University of Chicago Medical Center and Northwestern Memorial Hospital, had by far the most guardianship cases during the period examined, even in comparison to other big hospitals.

The Tribune identified 369 hospital-initiated adult guardianship petitions filed from January 2023 through June 2024 after combing through thousands of pages of court records in Cook, DuPage, Kane, Lake, McHenry and Will counties. Of these, 68 came from University of Chicago Medical Center and 35 from Northwestern Memorial. By contrast, Rush University Medical Center had six, John H. Stroger Jr. Hospital had five and Loyola University Medical Center had none.

The University of Chicago Medical Center filed 68 guardianship petitions in 18 months, the most by any hospital in the six-county Chicago area. (Eileen T. Meslar/Chicago Tribune)

The University of Chicago Medical Center filed 68 guardianship petitions in 18 months, the most by any hospital in the six-county Chicago area. (Eileen T. Meslar/Chicago Tribune)

The University of Chicago Medical Center and Northwestern both did not grant interviews and would not comment on individual cases, sending written general statements instead.

Northwestern called guardianship a “compassionate solution” and a “vital safeguard for individuals who are unable to make decisions for themselves and who lack family, friends or legal representatives acting in the patients’ best interest to advocate on their behalf.” The guardianship process “plays a critical role in protecting vulnerable patients,” said the statement from University of Chicago Medical Center, and the number of guardianship petitions it files “reflects the medical complexity and vulnerability of the patients we serve.”

Each hospital said guardianship is sought in only a fraction of cases — or, for Northwestern, “0.000175%” of the more than 200,000 patients the 11-hospital system discharged in a recent 12-month period.

For Ellis, his ordeal began when he injured his leg after falling on a fire hydrant, according to Brown. His father chose Northwestern Memorial for his treatment, believing it had the best care to offer in the area, Brown said. The injury, plus heart problems, resulted in Ellis moving back and forth between Northwestern and a nursing care facility.

Northwestern Memorial Hospital filed the second-largest number of guardianship petitions. A spokesperson called it a “compassionate solution” for some patients. (Eileen T. Meslar/Chicago Tribune)

Northwestern Memorial Hospital filed the second-largest number of guardianship petitions. A spokesperson called it a “compassionate solution” for some patients. (Eileen T. Meslar/Chicago Tribune)

Brown said he tried to go to the hospital every day after work, and before the guardianship he said he answered the phone at any time of the day or night when health care workers needed permission to perform procedures for his dad.

After learning of the guardianship petition, Brown sent an anguished, handwritten motion to the judge, pleading to be appointed guardian before the next court date at the end of August 2023. He had been in the process of visiting nursing homes but “didn’t move fast enough” for the hospital, the motion states.

“I don’t want my father passing in guardianship of the state when he has a whole family that loves him,” Brown wrote. “I honestly don’t know how they could say this when he’s had visitors almost every day literally!”

Two weeks later, his father died under guardianship of the state, in a long-term acute care hospital, with none of the people who loved him there to bear witness.

‘They weren’t listening’

In the best-case scenario, a hospital files a guardianship petition because there is no other viable option. Hospitals have a responsibility to discharge their patients safely, and some people who cannot function on their own do not have anyone close who is willing and able to take charge.

But the Tribune found multiple instances where patients had people who said they were willing to step in — or even held power of attorney — but the hospital filed a petition nominating someone else.

For example, when the University of Chicago Medical Center filed a guardianship petition for one patient in 2023 because of her cognitive impairment, the petition stated she had no close family members who were entitled to be notified regarding the guardianship.

But the patient did have a family, including her brother, William Donaldson, who told the Tribune he had been visiting her at the hospital. He said he was disappointed to find that his sister, 76, had been placed under guardianship and discharged to a nursing home.

“They kicked her out of the hospital without telling me,” Donaldson told the Tribune. “I had been going back and forth to the hospital to see her. I called the hospital looking for her and she was gone.”

Donaldson has since gained guardianship of his sister after four months in court with the help of an attorney. Of the situation, he said simply: “It is a nightmare.”

In some cases, as with Gary Brown, a hospital’s decision on guardianship had irrevocable consequences. Families saw the time run out on their loved one’s life before they could regain control.

Kenya Lawrence said she and other family wanted to take her grandmother, Earsline Rose, home with them to the Milwaukee area. Instead, Rose died in a South Side nursing home. (Eileen T. Meslar/Chicago Tribune)

Kenya Lawrence said she and other family wanted to take her grandmother, Earsline Rose, home with them to the Milwaukee area. Instead, Rose died in a South Side nursing home. (Eileen T. Meslar/Chicago Tribune)

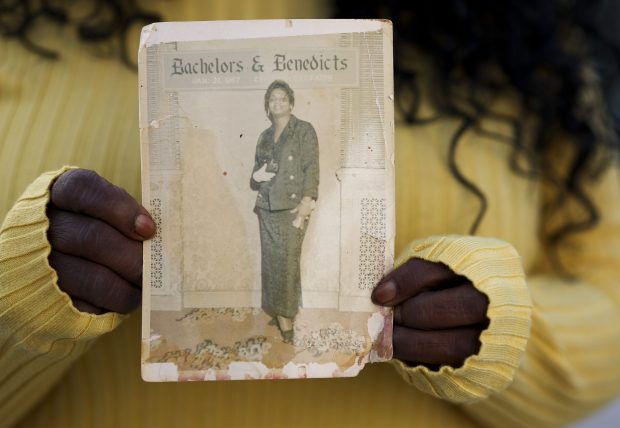

Kenya Lawrence, a granddaughter of the late Earsline Rose, told the Tribune she became aware of the University of Chicago Medical Center’s temporary guardianship petition only after Rose’s family found the paperwork in her hospital room.

Lawrence said she and her siblings showed up at a 2023 court hearing on the petition for Rose, who was 90 years old, and tried unsuccessfully to make the case that the family should be in charge.

“She had no business in the system; she has relatives,” Lawrence said. “I fought tooth and nail; I fought very hard. They weren’t listening to that.”

Rose’s grandchildren had hoped to take the nonagenarian home with them to the Milwaukee area and care for her in her final days. Instead, she was discharged to a poorly rated nursing home in Chicago’s South Shore neighborhood, many miles away. She died there in July 2023, four days after Lawrence formally petitioned a judge to take over as her grandmother’s guardian, records show.

For Rose’s family, the process felt “shady,” frustrating and cruel.

“Everybody’s going to get old,” Lawrence said, “and you’re going to wish that doesn’t happen to you.”

“She had no business in the system; she has relatives,” Kenya Lawrence said of her grandmother, Earsline Rose, shown in an old publication. (Eileen T. Meslar/Chicago Tribune)

“She had no business in the system; she has relatives,” Kenya Lawrence said of her grandmother, Earsline Rose, shown in an old publication. (Eileen T. Meslar/Chicago Tribune)

Though the University of Chicago Medical Center would not comment on individual cases, it contended in its written statement that “the medical center pursues guardianship … only after exhaustive efforts are made to locate family or close friends.”

Joyce Anderson told the Tribune it came as a surprise when Chicago’s St. Mary of Nazareth Hospital filed a petition naming a private organization as the recommended guardian for her 81-year-old aunt, Betty Robertson, instead of anyone who knew her.

It happened, Anderson said, while she was still working on finding an acceptable facility where her aunt could live after discharge. As she made calls and visited nursing homes, various family members continued visiting the elderly woman at the hospital.

Once guardianship was in place, the hospital sent Robertson to a nursing home that Anderson did not find to be acceptable for someone she loved. Robertson has since died.

“They did not care, that’s the best way for me to put it,” Anderson said of the hospital. “I understand financially, I understand about all of that, but you should have just given us more of a chance to try to find some place.”

Ascension, which owned the hospital at the time, did not answer Tribune questions. Court records show that a nurse had acknowledged that relatives regularly visited the patient but said the family was “nonresponsive” regarding medical decisions.

Derrell Collier said he spent hours at his mother’s bedside after she went into cardiac arrest outside a grocery store at age 69 in early 2023 — mainly at Loyola University Medical Center and then at Kindred Chicago Lakeshore, a long-term acute care hospital that has since closed.

Derrell Collier washes the hands of his mother in October at a Chicago nursing home. A hospital had previously tried to place her under guardianship. (Eileen T. Meslar/Chicago Tribune)

Derrell Collier washes the hands of his mother in October at a Chicago nursing home. A hospital had previously tried to place her under guardianship. (Eileen T. Meslar/Chicago Tribune)

After several months, Collier said, Kindred told him his mother’s insurance would soon cease to cover her stay and the hospital wanted to discharge her. Collier was opposed, and while he was still navigating how to get his mother’s care covered, Kindred’s administration grew impatient and sought the appointment of a public guardian in the fall of 2023, writing in a petition that her “family refuses to participate and consent to discharge planning.”

Collier, who had his mother’s power of attorney for health care, said he showed up for court to argue that he and his brother were very much involved, present and able to act on the wishes his mother had expressed before she fell ill. The hospital withdrew the guardianship petition after Collier found another placement for his mother.

“When you show up every day it’s difficult for them to do certain things, it’s hard to go in front of a judge and say he doesn’t care,” Collier said. “They took me there because of the money. … They were trying to take charge and stick her in any-old-nursing-facility any-old-where.”

A spokesperson for ScionHealth, which operated Kindred Chicago Lakeshore, declined to comment on specific patients. In a written statement, the health system said the “safety, dignity and well-being of our patients are always our highest priorities.”

Nearly a third of patients in the hospital guardianship cases reviewed by the Tribune went to nursing homes that, during the year the guardianship was initiated, had an average one-star rating from the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, the lowest possible. A similar percentage of patients were discharged to nursing homes that were flagged for patient abuse for the majority of the year in which they were placed under guardianship.

“They were trying to take charge and stick her in any-old-nursing-facility any-old-where,” Derrell Collier said of the now-closed hospital that wanted to discharge his mother against his wishes. (Eileen T. Meslar/Chicago Tribune)

“They were trying to take charge and stick her in any-old-nursing-facility any-old-where,” Derrell Collier said of the now-closed hospital that wanted to discharge his mother against his wishes. (Eileen T. Meslar/Chicago Tribune)

In one case, the University of Chicago Medical Center nominated the mother of a 53-year-old patient as guardian in October 2023, only to renege after the mother objected to the poorly reviewed nursing home the hospital had selected for discharge, RYZE on the Avenue.

In the months before the hospital filed its petition, federal regulators had fined that nursing home more than $80,000 after finding the facility had failed to protect residents from physical abuse from other residents, failed to properly care for wounds and left an incontinent patient in soiled clothing for more than two hours.

The hospital nominated a different guardian, and the patient was discharged to the nursing home. She died months later. RYZE did not respond to the Tribune’s requests for comment.

Jim Berchtold, a Nevada attorney and the recent director of Justice in Aging’s guardianship policy program, said that when hospitals are the ones arranging for discharge, the focus is on getting the person out the door.

“They don’t care what level of care they’re receiving, they can say, ‘It was a safe discharge, we’re in the clear,’” said Berchtold, who developed a program to provide legal counsel for adults facing guardianship in his home state of Nevada. They may think: “‘Hopefully … the guardian will step in and transfer them someplace better.’ (They’re) pushing it off to the next person.”

Choosing the ‘nuclear option’

Once a guardianship is in place, it takes time, money and effort to make the case for freedom.

Brian Sivley, a 36-year-old man with physical disabilities, wound up under guardianship after he suffered a fall, was treated at Northwestern Memorial Hospital and didn’t like the hospital’s plan to discharge him to a nursing home. A hospital doctor determined Sivley had an “inability to appreciate the risks of returning home.”

Sivley had lived in a nursing home before, but he’d recently succeeded in living on his own with the help of government services. He wanted to keep his hard-won autonomy.

Northwestern officials filed a petition for temporary guardianship anyway. It would take a year before Sivley, with legal help from the disability advocacy organization Equip for Equality, was able to resume making his own health and living decisions.

The hospital withdrew its petition for a longer-term guardianship arrangement earlier this year after Sivley signed documents giving his power of attorney for health care to a former teacher he had stayed in touch with over the years.

“I don’t know why they took the nuclear option,” Sivley’s attorney, Jin-Ho Chung, said of the hospital. “Like the doctor that we retained said, one might agree or disagree with Mr. Sivley’s choices; that doesn’t mean that he needs a legal guardian.”

“From our experience, it seems that it’s more difficult for individuals to terminate a guardianship than to have one appointed,” said Cristina Headley, another attorney with Equip for Equality who works on the organization’s adult guardianship initiatives.

In a written statement, Sivley told the Tribune he “felt really mad” about the forced guardianship.

“I knew that there were ways I could get rehab at my apartment and it would be covered by my insurance because of prior experiences,” Sivley wrote. “It hurt even more because I had just moved into my first apartment.”

Anita Raymond, a licensed independent social worker who has written about the so-called hospital-to-guardianship pipeline, said hospitals may err in relying on the court’s checks and balances to catch questionable petitions.

“Hospitals may think, ‘We don’t know what else to do. If we’re wrong the court-appointed attorney will fight the petition,’” Raymond said, referring to the guardian ad litem who helps assess what decision is in the person’s best interest. “And then the judge ultimately decides whether to appoint the guardian or not. People presume, ‘It’s OK if I do this even if I’m wrong.’”

But health professionals and other advocates say these judges often don’t have much more information to go on than the medical evaluations coming from the hospital itself, which has a vested interest in the outcome.

Cook County Circuit Judge Daniel Malone, who presides over the probate division, said in an interview that the judges make decisions based on the information in front of them. The standard for finding someone to be disabled — clear and convincing evidence — is high, he said.

“We’re taking people’s rights away from them,” Malone said. “It’s not something any judge here wants to do lightly.”

The medical evaluations provided to the court also are sometimes conducted early in the person’s stay, when they may be at their worst, advocates said.

Andre Daniels, left, brings food to his father, Frank Daniels, at a La Grange Park nursing home this month. Andre Daniels is now his father’s guardian after a fight in court. (Eileen T. Meslar/Chicago Tribune)

Andre Daniels, left, brings food to his father, Frank Daniels, at a La Grange Park nursing home this month. Andre Daniels is now his father’s guardian after a fight in court. (Eileen T. Meslar/Chicago Tribune)

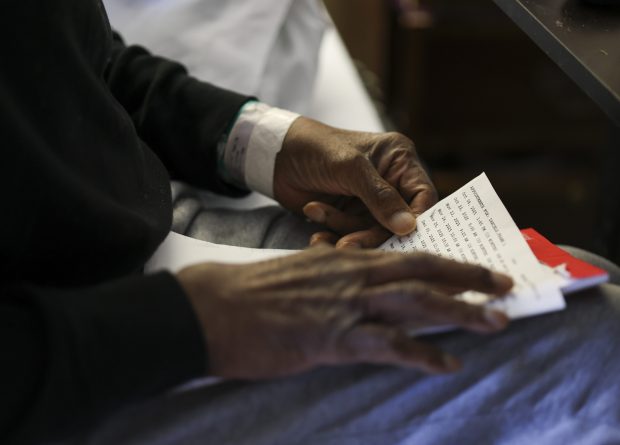

Andre Daniels, whose father was placed under temporary guardianship at age 76 in February 2024, said he is bothered by the fact that Frank Daniels was assessed at the beginning of his hospitalization and his ability to make decisions was not meaningfully reevaluated afterward.

“He’s very perceptive, he’s very aware, he still writes everything down,” Daniels said of his father. “How did he get to the stage where he was deemed incapable (when) he is basically capable?”

The younger Daniels said he had been estranged from his father, a trained welder who served in Vietnam as a Marine, before learning about the situation from his brother in October 2024. He then worked with an attorney to take over as guardian earlier this year.

Much of what the elder Daniels has to his name was the result of fighting and advocating for himself, according to his son. In the late 1980s, Daniels won a racial discrimination lawsuit, along with a substantial financial settlement, after complaining about unequal treatment for Black welders in the white-dominated Chicago Pipefitters Local 597 union. His fight had lasting effects, with a federal judge later mandating oversight of the union’s practices.

He is now in a nursing home but wants to return to the multifamily home he owns and lived in with two of his daughters before being treated at University of Chicago Medical Center, Daniels said. He said they are now working toward that goal together.

Frank Daniels, shown holding a list of appointments, is “very perceptive, he’s very aware,” his son said. “How did he get to the stage where he was deemed incapable (when) he is basically capable?” (Eileen T. Meslar/Chicago Tribune)

Frank Daniels, shown holding a list of appointments, is “very perceptive, he’s very aware,” his son said. “How did he get to the stage where he was deemed incapable (when) he is basically capable?” (Eileen T. Meslar/Chicago Tribune)

The Tribune’s review found Black patients were overrepresented in hospital guardianship petitions in diverse Cook County, raising questions of implicit bias in both health systems and the courts related to those patients and their families. While the patient’s race was not always available in court records, at least 39% of the patients were identified as Black, compared with about 22% of the county’s population.

“There are hundreds of decision points, even before the case is filed, about that person, about their capacity, about their behaviors, about the decisions they are making,” said Berchtold, formerly of Justice in Aging. “The people making those decisions are almost inevitably white individuals who know nothing about this person or where that person is coming from.”

Dr. Kahli Zietlow, a geriatrician and clinical associate professor at the University of Michigan who is studying guardianship outcomes, said physicians who see patients in a hospital setting may have no history with the patient, don’t know firsthand how well the person might function at home and may not completely understand the implications of their evaluations.

“Physicians don’t necessarily realize when we write a letter (finding someone incapacitated) … that it can mean forever,” she said.

The Tribune found one case where a man is still under guardianship more than a year after the state guardian itself filed a petition with the court requesting to release him.

Gottlieb Memorial Hospital, which is part of Loyola Medicine, initiated the petition in 2022 for the man in his early 60s because complications related to alcoholism had left him unable to comprehend or communicate much, court records show. He spent about 45 days in the hospital.

But after his discharge to a nursing home, the former patient improved greatly and repeatedly voiced his objection to being under guardianship and living at the facility. A 2024 petition from the state guardian to revoke the guardianship stated “he is completely independent and does not have any major medical issues and does not display any sign of confusion.”

That petition is still pending after the last doctor to evaluate the man requested a second opinion and the second doctor got cold feet about doing the evaluation, telling the man’s guardian she feared the consequences to her license if the man “were to commit a crime.” This month, the guardian reported to the court that another doctor requested additional sessions with the man before issuing a report.

Loyola Medicine said it could not share information about an individual patient but said it is the health system’s policy to ask for court intervention “only after we have exhausted other available options.”

“It’s a tough system,” said Peter Lichtenberg, a national expert in financial capacity assessment and the financial exploitation of older adults. “If somebody who really shouldn’t have lost their rights but doesn’t have the wherewithal to have the legal advocate to get them on their road … it can be a real nightmare.”

Alternatives to guardianship

Stroger is Cook County’s flagship public hospital and aims to “care for everyone” regardless of immigration status or the ability to pay. Around half of the patients in recent years have been Medicaid recipients — meaning many belong to lower-income households.

Yet despite the complications of caring for this population, the hospital brought just five guardianship petitions during the 18-month period the Tribune examined. Two of the cases involved a pair of siblings in their 40s with serious disabilities who had been at Stroger for nearly two years.

Cook County Health’s chief legal officer, Ellie Bane, said in a statement that Stroger strives to preserve patient autonomy and that the hospital works to find alternatives such as powers of attorney or surrogate decision-makers for health care.

“A guardianship for health care decisions is a significant legal decision that requires court approval and can be overly restrictive, and even permanent,” Bane wrote. “Pursuing guardianship when other options exist extends beyond our primary role as a health care provider.”

With his son’s help, Frank Daniels hopes to leave nursing care and return to the multifamily home he owns and lived in with his two daughters. (Eileen T. Meslar/Chicago Tribune)

With his son’s help, Frank Daniels hopes to leave nursing care and return to the multifamily home he owns and lived in with his two daughters. (Eileen T. Meslar/Chicago Tribune)

At St. Bernard Hospital and Health Care Center, a smaller community hospital in Chicago’s Englewood neighborhood, those who oversee case management told the Tribune that even in cases where patients are difficult to discharge, they seek to work with family members or other decision-makers whenever possible. St. Bernard filed just one petition for guardianship between January 2023 and June 2024.

Vivian Moore, who works in the hospital’s wellness management department, said the hospital starts discharge planning the day patients are admitted. She said the hospital does its own investigations to find family members, including researching prior visits and searching for missing persons reports.

“If the patient doesn’t have a preference or is not able to vocalize a preference we want to take into consideration the preference of the family,” Moore said. And when patients disagree with what the hospital thinks is best, St. Bernard also tries to honor that, she said. “We still want to equip them with those options and resources, but we respect their final decision.”

St. Anthony Hospital in Little Village filed just two guardianship petitions in the 18 months the Tribune reviewed. David Evers, the hospital’s assistant general counsel, called it “a last resort … in part because we have a lot of great alternatives under Illinois law that are not permanent, that are less invasive, that give families more input.”

“It does cost you a lot of money and effort to get a guardian appointed, so if there is a family member that wants to be a guardian and is engaged with us, we’re absolutely going to help them do it because it’s in both of our interests,” Evers said.

An Illinois law aimed at reducing guardianship does require health providers to seek out potential surrogate decision-makers for the patient, but that requirement extends only to spouses, parents and children. Contacting adult grandchildren, siblings and close friends is optional.

In four Michigan counties, the Michigan Elder Justice Initiative is operating a pilot program aimed at offering courts and community organizations alternate tools to help solve problems without fully stripping away adults’ rights.

Alison Hirschel, an attorney with the advocacy organization, said that in one county they saw a 42% reduction in guardianship filings in the program’s first year.

“There are lots of reasons that hospitals and nursing homes petition for guardianship that aren’t really about the interests and best needs of the patient,” Hirschel said.

One key component of the Michigan program is educating petitioners about options that are less restrictive than full guardianships.

Derrell Collier washes the feet of his mother during a recent visit to her nursing home. “She took care of everyone in the family,” he said. “I think it’s only right. It’s her turn.” (Eileen T. Meslar/Chicago Tribune)

Derrell Collier washes the feet of his mother during a recent visit to her nursing home. “She took care of everyone in the family,” he said. “I think it’s only right. It’s her turn.” (Eileen T. Meslar/Chicago Tribune)

In Illinois, one such option is limited guardianship, which is specifically tailored to the things a person needs assistance with.

But in the Tribune’s 18-month review, just seven of the hospital-initiated guardianships, or roughly 2%, were limited in nature, allowing the person some control over their life. In at least one situation, the guardian ad litem’s recommendation for a limited guardianship was disregarded.

In that case, a former University of Chicago mathematics professor was hospitalized at the university’s medical campus in fall 2023 after his advanced dementia resulted in a friend and colleague bringing him to the hospital.

After meeting the former professor, the guardian ad litem wrote to the judge that he “uses his intelligence to mask possible dementia and cognitive deficits” but “I do not think the respondent is totally unable to make personal or financial decisions.”

The man consistently objected to needing guardianship but agreed he could use some help managing his financial affairs. Nonetheless, a full guardianship was put into place.

“There really is supposed to be a preference for limited guardianships,” Hirschel said. “One of the reasons that rarely happens or doesn’t happen nearly as often as it should (is) the judges don’t have enough information about what the person can do or can’t do. The judge doesn’t have the information to draft a narrowly tailored order. And also for judges who are really busy, it’s just faster.”

Malone, who presides over Cook County’s probate division, acknowledged to the Tribune that limited guardianships are in the minority. In making those decisions, Malone said, judges have to rely heavily on the reports they receive.

“It’s the doctors that make that decision as to whether the person’s totally disabled or partially disabled,” he said. “The other thing we rely heavily upon is (guardians ad litem); they’re the eyes and ears of the court.”

Other best practices experts cited to improve the guardianship process include bolstering training for physicians who conduct these assessments and doing the assessments in home settings whenever possible.

Gary Brown sits on a South Michigan Avenue bench where his father, Gary Ellis, a former CTA bus driver, liked to sit and watch activity near a bus stop. Brown said his feelings are still raw after his father died under guardianship without loved ones nearby. (Eileen T. Meslar/Chicago Tribune)

Gary Brown sits on a South Michigan Avenue bench where his father, Gary Ellis, a former CTA bus driver, liked to sit and watch activity near a bus stop. Brown said his feelings are still raw after his father died under guardianship without loved ones nearby. (Eileen T. Meslar/Chicago Tribune)

Dr. John Halphen, a clinical professor of geriatric medicine at UTHealth Houston, has worked for about two decades with a state-funded program that connects physicians trained in capacity assessments with adult protective services, which now covers the entire state of Texas.

The physicians he works with “don’t have a dog in the fight,” Halphen said; no one involved receives fees or gets paid in a way that is related to the outcome of the assessment.

Obtaining background information about the person is key, Halphen said. His team checks with multiple sources to learn about the adult’s capabilities and uses cognitive screening tests to help assess whether people really understand their circumstances.

“It’s always a balancing act,” said Lichtenberg, the expert on financial assessment. “If you don’t provide protection to people who are incredibly vulnerable, they do get exploited and it’s not pretty.

On the other hand, “if you provide protection when you should be promoting autonomy, it impacts their quality of life and mental health,” he said. “It impacts their physical health too. The stakes are very high for guardianship when it’s a close call.”

‘How can they do that’

For Gary Brown, whose father died under guardianship and without loved ones nearby, feelings remain raw that no one has been held accountable for the way his father’s story ended.

“They really took a lot from me and out of me,” Brown said.

His aunt Sandra Ellis told the Tribune she had been keeping tabs on her brother, including visiting periodically from Georgia, talking to hospital officials and reaching out to confirm her brother’s insurance was still covering his stay.

She said she did not know this was something hospitals could do — ask the state to take control of a person.

“How can they do that and get away with all of that?” Ellis asked. “When he passed away there was not one single family member that he had there with him. And that was so sad.”

Chicago Tribune’s Hope Moses contributed.

ehoerner@chicagotribune.com

cmgutowski@chicagotribune.com

lschencker@chicagotribune.com