BANGOR, Maine (BDN) — Bangor is the epicenter of Maine’s largest ever HIV outbreak. But the ripple effects from the cluster first identified in Penobscot County in October 2023 are being felt across the state.

Health care providers are confident that the outbreak will lead to new cases outside the Bangor area, and some local governments and community organizations are taking proactive steps to get ahead of that spread.

Their efforts reflect an awareness that the outbreak will likely reach beyond Penobscot County and affect the entire state. They also come at a critical time when threats to public health infrastructure at the federal level could jeopardize efforts to contain the outbreak.

“Public health providers in the southern Maine area kind of circled up and we’ve been having conversations around how to prepare for a similar outbreak,” said Katie Rutherford, the executive director of Portland’s Frannie Peabody Center. The organization is dedicated to providing support to people with HIV/AIDS.

Multiple people involved with municipal and nonprofit public health organizations outside of Penobscot County told the Bangor Daily News that these preparations are a necessary step in the face of the outbreak.

“I would be more surprised if we didn’t see any cases,” said Bridget Rauscher, Portland’s public health director. “We don’t know for sure the extent of this outbreak, which I think is kind of important to remember. We only know what we’ve tested, right?”

Rutherford and Rauscher’s organizations have both been ramping up HIV testing efforts in southern Maine.

In April, Portland’s health department announced it was adding a walk-in testing day to its STD clinic, citing the HIV outbreak in Penobscot County.

Maine’s largest city is also encouraging more frequent testing, offering more testing certification trainings, and partnering with homelessness and recovery organizations to administer tests in the community, according to Rauscher.

“We generally will encourage people to test for HIV and hepatitis C every three to six months. We’ve moved that up to every one to three months,” she said.

The Penobscot County outbreak is largely affecting people who are homeless or use drugs. Rauscher said her department is particularly focused on testing residents who share those risk factors or who said they’ve recently come to Portland from Bangor.

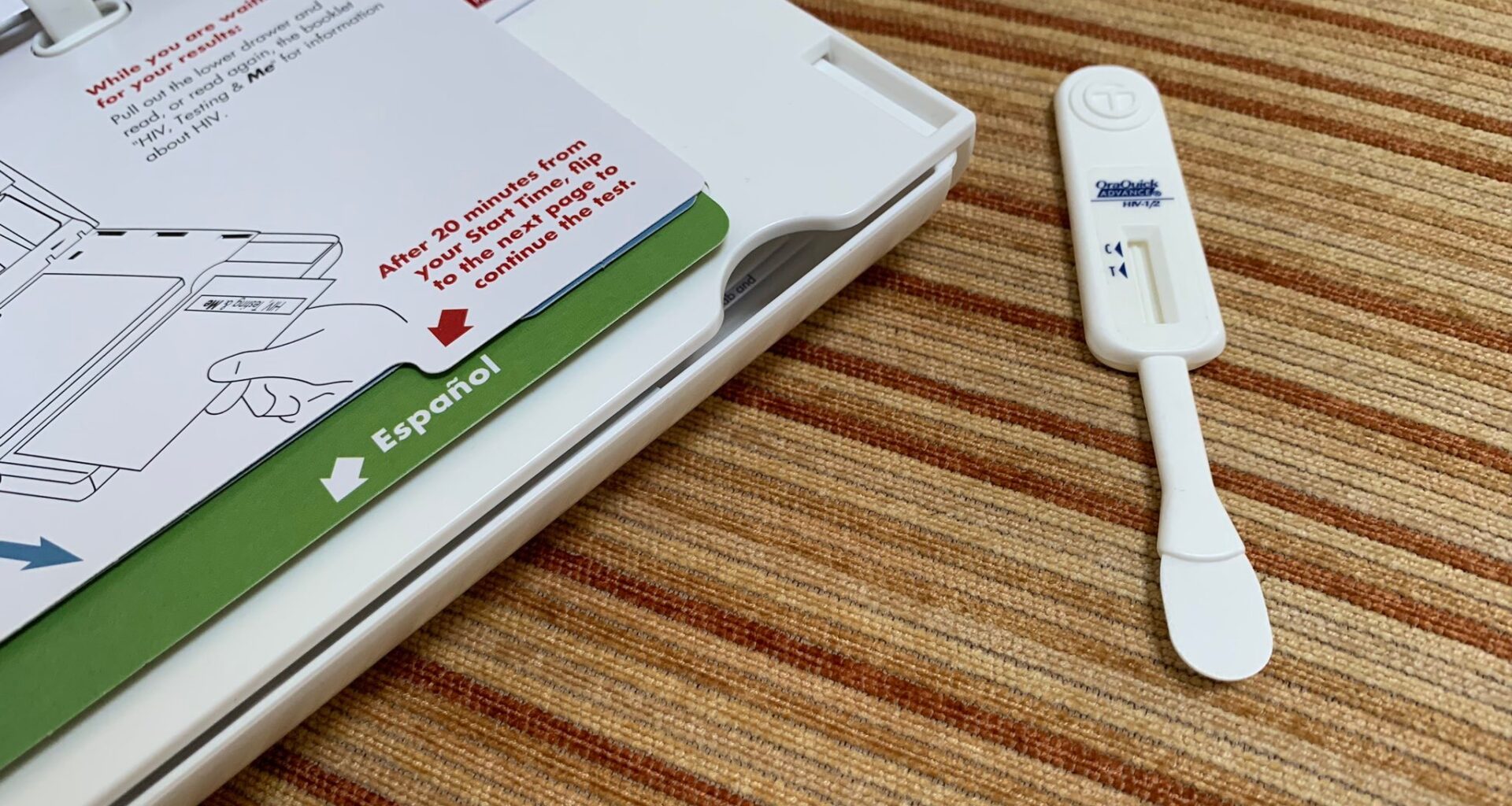

HIV self-test kits have also been crucial for organizations with limited staff, and deploying staff out into the community has helped reach more people with testing.

“They’re very user-friendly self-test kits and it’s just an oral swab. It’s nothing painful or really even uncomfortable in the way that the nasal swabs were with COVID,” Rutherford said. Her organization distributes more than 1,500 tests every year.

Some smaller cities are starting efforts to ramp up testing.

Officials in Augusta are looking into ways the city could provide HIV self-test kits, according to Steve Leach, Augusta’s deputy fire chief and health officer.

“The city itself doesn’t have a big footprint involved in [HIV prevention] right now,” he said, but conversations with people in Penobscot County who are working to mitigate the outbreak prompted him to consider new solutions.

Emergency medical services teams already bring naloxone, the overdose reversal drug often known by the brand name Narcan, when responding to substance use calls, Leach said.

He’s looking into whether the city could also distribute HIV tests this way, which would require approval from the state, or if it would be possible to distribute them through other agencies in the city.

Much of the HIV prevention work in Augusta is done by MaineGeneral, the nonprofit health care system headquartered there. The health system works with harm reduction programs, Maine Family Planning and social service organizations to provide testing, safe sex supplies, clean syringes and connections to treatment, according to Shane Gallagher, MaineGeneral’s director of HIV and harm reduction services.

Last month, the health system announced that it was expanding its federally funded HIV/AIDS medical services to cover nearly all of Maine’s counties. It also operates a syringe service program in Augusta and Waterville.

The organization has been working to increase testing and provide more home test kits, Gallagher reported.

Throughout the state, the Maine Center for Disease Control and Prevention is coordinating with organizations like MaineGeneral to replicate what’s being done in the Bangor area to other cities and towns, according to Anne Sites, Maine CDC’s director of infectious disease prevention.

“One thing we’ve seen in Penobscot County is a really successful initiative to enhance our reach around PrEP,” she said, referring to the medication that reduces the risk of contracting HIV. She noted ongoing conversations with Maine Family Planning about using mobile services to provide PrEP in the Lewiston-Auburn area.

Maine CDC is also encouraging clinical providers across the state to focus on the syndemic of HIV, STDs, hepatitis and substance use disorder — a concept that refers to the way co-occurring epidemics can exacerbate each other — and test simultaneously for HIV and other diseases, Sites said.

Most of the HIV cases identified as part of the Penobscot County outbreak appeared alongside cases of hepatitis C.

Public health organizations have also stressed that syringe services, a type of harm reduction that involves providing people who use drugs with clean needles, are a key part of HIV prevention.

Syringe service programs are proven to reduce HIV and hepatitis C transmission rates by around 50%, according to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Their organizers often provide other services, including testing for HIV.

In 2024, syringe service providers in Maine conducted 526 HIV tests onsite, according to a report from the state’s Department of Health and Human Services. That number is up from 373 in 2023 and 96 in 2022. The most recent report also detailed 4,498 referrals by Maine syringe service providers to outside organizations for testing and care for viral hepatitis, STDs and HIV.

But while Portland’s syringe exchange has been operating for more than 25 years, syringe service programs face resistance in some of Maine’s smaller cities because of concerns about needle waste or misconceptions that they will encourage drug use.

“It is often politicized. But it’s an effective public health strategy,” Rauscher said.

Multiple municipalities in Maine are currently working to limit syringe exchange services. Auburn instituted a six-month moratorium on needle exchange programs in August, while Sanford is considering banning needle distribution altogether, according to an October report by City Manager Steven Buck.

A spokesperson for the city of Auburn did not respond to a request for comment.

Lewiston passed an ordinance last month limiting the city to just one syringe service provider. In response to a question about whether the city of Lewiston is monitoring the outbreak and preparing for it to spread, city spokesperson Angelynne Amores wrote, “Maine CDC measures that — it is not measured locally.”

Any local efforts to combat HIV spread could be overshadowed by proposals at the federal level to eliminate funding for such services.

The House appropriations bill for next year proposed cutting $1.7 billion in funding for HIV programs, including completely eliminating HIV prevention programs and reducing care and treatment funding by 20 percent, according to the HIV and Hepatitis Policy Institute.

The proposed budget was “very bad timing for Maine,” Matt Wellington, the associate director of the Maine Public Health Association, said.

Public health officials in Maine have also struggled to get support from the U.S. CDC amid the Penobscot County outbreak. In October, the federal agency paused a request to send field epidemiologists to help manage the outbreak, partly because of the government shutdown, the Boston Globe reported.

“In a small state like Maine where it’s not normal for us to have HIV outbreaks of this size, we’re just not equipped to handle it by ourselves,” Wellington said.

He and others in Maine’s public health sphere agreed that resources and funding are essential for supporting the people who have been diagnosed with HIV and for preventing new spikes in cases.

“People can live healthy lives with HIV,” Rutherford said, “but I think people also need to understand that if these robust programs were to go away and people don’t have access to their medications, then it might as well be 1981 again.”