Study area

We investigate the isolated and compound impacts of multiple flood drivers on the road infrastructure systems of the coastal city of Kozhikode, located in Kerala, India. The study domain encompasses the municipal corporation region of the city, which is part of the Kallai River catchment (Fig. S1). This complex urban area experiences the spatial convergence of flood-inducing factors such as extreme precipitation, riverine overflow, and tidal surges. The region features a highly undulating topography, with the eastern part of Kozhikode characterized by landforms such as beach ridges, sandbars, and backwater marshes. Moving a few kilometers inland, the terrain transitions into slopes and clustered hills interspersed with numerous valleys. The study area experienced an extreme precipitation event in August 2018, resulting in 16 fatalities and about 50,000 houses severely affected by floods37.

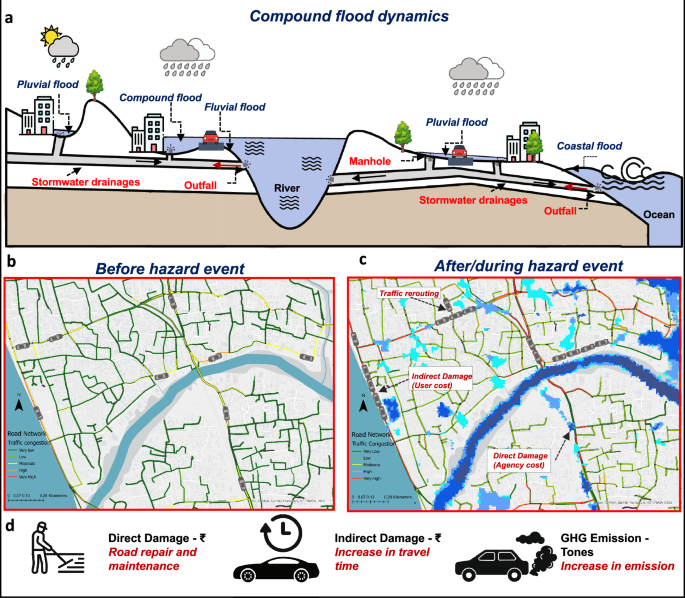

Flood hazard model

Flood hazard estimation was conducted using the MIKE+ software40, which employs an implicit finite difference numerical scheme to solve the full shallow water equations56. The modeling process begins with the solution of the 1D shallow water equations to simulate flow in stormwater drainage and river channel flows. Subsequently, the model extends to solve the full 2D Saint-Venant equations, integrating the 1D and 2D flows for a comprehensive simulation. The governing equations include the continuity equation and two momentum equations, each representing flow dynamics in orthogonal directions.

$$\frac{\partial {\bf{U}}}{\partial t}+\frac{\partial {\bf{F(U)}}}{\partial x}+\frac{\partial {\bf{G(U)}}}{\partial y}={\bf{S(U)}}$$

(1)

where,

$$\begin{array}{l}\qquad{\bf{U}}=\left[\begin{array}{c}h\\ hu\\ hv\end{array}\right],\quad {\bf{F}}({\bf{U}})=\left[\begin{array}{c}hu\\ h{u}^{2}+\frac{1}{2}g{h}^{2}\\ huv\end{array}\right],\\\,\,{\bf{G}}({\bf{U}})=\left[\begin{array}{c}hv\\ huv\\ h{v}^{2}+\frac{1}{2}g{h}^{2}\end{array}\right],\quad {\bf{S}}({\bf{U}})=\left[\begin{array}{c}0\\ -gh\frac{\partial z}{\partial x}+{S}_{x}\\ -gh\frac{\partial z}{\partial y}+{S}_{y}\end{array}\right]\end{array}$$

where U represents the state vector containing the conserved quantities, F(U) and G(U) are the flux vectors in the x and y directions, respectively. S(U) is the source term vector accounting for bed slope and other forces.

To accurately represent the complex topography of Kozhikode city, high-resolution elevation data with a 10-meter spatial resolution from CartoDEM47 provided by the National Remote Sensing Centre (NRSC) was utilized. Additionally, the National Centers for Environmental Information (NCEI) Coastal Elevation Model was employed to capture the ocean bathymetry near the coastal region57. For river bathymetry, Acoustic Doppler Current Profiler (ADCP)58,59 and Real-Time Kinematic Differential Global Positioning System (RTK DGPS) devices were used to measure river depth and velocity across multiple cross-sections (Fig. 2e). The Digital Elevation Model (DEM) was further refined through hydroconditioning processes. Initially, CartoDEM and NCEI Coastal DEM elevations were merged at the coastline. Subsequently, the DEM was hydroconditioned within the river channel by adjusting elevations to align with river bathymetry data collected through in situ measurements (Fig. 2c). The hydrodynamic model was configured to ensure the most accurate and robust simulation outcomes. A triangular irregular network (TIN) mesh was generated to represent the terrain’s topographical properties, with grid sizes ranging from a minimum of 1 m2 to a maximum of 200 m2 within the domain boundary. Furthermore, the Manning roughness coefficient was developed to model flow resistance based on the land use land cover (LULC) map derived from a combination of Sentinel-1 and Sentinel-2 10-meter raster grids. The methodology and accuracy of the LULC classification are detailed in (Note S1 and Fig. 2d). The MIKE+ model was set up to simulate the following hazard models.

The pluvial flood model was configured using precipitation inputs from ERA5-Land reanalysis for a 72-hour extreme rainfall event in 2018 at a spatial resolution of 0.1∘ and an hourly temporal scale60. The 50-year and 100-year design rainfall intensities were derived through flood frequency analysis using the Generalized Extreme Value (GEV) method, as detailed in (Note S2). In the pluvial flood scenario, infrastructure plays a crucial role in managing surface runoff. The model incorporated stormwater drainage data, including 6274 manholes, 6278 pipes, and 66 outfalls, to accurately represent the drainage network’s capacity and flow dynamics (Fig. 2a, b). To simulate the isolated pluvial flood scenario, the river stage during the low-flow period was considered, with no tidal influence at the stormwater drainage outfalls. The flow in stormwater drainage is solved through the 1D-Saint Venant equation (Eq. (2)) and later coupled with 2D-overland flow solved by (Eq. (1)).

$$\begin{array}{l}\qquad\qquad\quad\,\,\frac{\partial A}{\partial t}+\frac{\partial Q}{\partial x}=0\\ \frac{\partial Q}{\partial t}+\frac{\partial }{\partial x}\left(\frac{{Q}^{2}}{A}+gAh\right)=gA({S}_{0}-{S}_{f})\end{array}$$

(2)

where A is the cross-sectional area of the flow, Q is the flow discharge, h depicts flow depth, S0 and Sf are bed and friction slope, respectively.

The fluvial flood scenario was configured by specifying the water source in the river stream. Due to the absence of a gauge station in the Kallai River catchment, the parameter regionalization with the donor catchment approach was employed61 to simulate the hydrological model. The nearby Chaliyar River catchment, which shares similar topography and land-use characteristics, was modeled using the SIMHYD (Simple hydrology model), a conceptual rainfall-runoff model that simulates streamflow based on rainfall, evapotranspiration, and catchment characteristics62,63. The model was configured with precipitation data and GLEAM (Global Land Evaporation Amsterdam Model) potential evapotranspiration data64. The model was calibrated and validated against observed streamflow data from INDIAWRIS (India Water Resources Information System)65, and the validated parameters were transferred to the un-gauged Kallai River catchment to estimate streamflow for the fluvial flood scenario (Fig. S2). A detailed explanation of the hydrological model is provided in (Note S1). The simulated streamflow was used as a boundary condition for the hydrodynamic model. The hydrological model was applied across the upstream catchment area of the Kallai river to capture runoff generation, while the hydrodynamic model encompassed the river channel and adjacent floodplains within the urban extent of the Kozhikode Municipal Corporation to simulate inundation dynamics. The 50-year and 100-year flow rates were estimated based on flood frequency analysis using the GEV method, as detailed in (Note S2). In situ, river cross-sections were incorporated for 1D river channel flow to simulate the isolated fluvial flood scenario, which was then coupled with 2D overland flow (Fig. 2e). Flow contributions from stormwater drainage outfalls and tidal levels were not accounted for in this scenario.

The coastal flood scenario was developed using hourly tide level data from in-situ tidal sensors provided by the Indian National Centre for Ocean Information Services (INCOIS)66. The 50-year and 100-year tide levels were estimated using the peak-over-threshold method, as detailed in (Note S2). This scenario incorporates tide fluctuations through shallow water equations for an area extending a few kilometers from the coast. However, it does not account for additional coastal flood drivers such as wave transformation, runup, and overtopping27. The tide levels were incorporated into the hydrodynamic model as a 2D boundary condition, while the influence of stormwater drainage outfalls and upstream river inflows was excluded to create an isolated coastal flood scenario.

Each hazard scenario (pluvial, fluvial, and coastal) was fully integrated into the hydrodynamic model. The stormwater drainage outlets were connected to the river channel to couple the pluvial and fluvial floods, while outlets discharging into the ocean were linked to tide levels to account for coastal-pluvial flood interactions. Additionally, the downstream section of the river channel was coupled with the coastal boundary through tide levels, ensuring dynamic interaction between each hazard driver. The baseline, 50-year, and 100-year precipitation intensity, streamflow, and tide levels were used to generate the corresponding return period boundary conditions for compound flooding scenarios.

The hydrodynamic model representative of the compound flood scenario was validated using two complementary approaches. First, the 72-hour event from August 14 to August 17, 2018, was simulated by incorporating streamflow, precipitation, and tide levels to create a baseline scenario. The simulated flood depths showed an 80% match with observed depths at 104 points provided for Kozhikode Corporation by the Kozhikode corporation by the Kerala State Disaster Management Authority (KSDMA)67,68. Second, the model’s flood inundation extent was validated using Sentinel-1-derived water body extents to ensure consistency with observed flood inundation patterns. This comparison yielded an overall accuracy of 0.77, an F1 score of 0.783, and a kappa coefficient of 0.419 when compared to satellite-derived flood maps. Here, overall accuracy represents the proportion of correctly classified flood and non-flood grid cells compared to the satellite-derived reference map (Note S3 and Fig. S3).

Direct (agency) cost analysis

The impact of floods on roads was assessed by analyzing both direct and indirect damages. Road network data were sourced from OpenStreetMap (OSM)69, which provided road width classifications based on OSM-defined categories such as highway, primary, secondary, tertiary, and residential roads. Direct economic damages were quantified using a depth-damage function database developed by ref. 70, which estimates flood-related losses on a national scale. These depth-damage functions range from 0 (no damage) to 1 (complete damage), reflecting the proportion of damage relative to flood depth. For this study, the maximum loss value and depth-damage functions specific to India were utilized, with road infrastructure considered as the primary exposure element. The depth-damage function was applied based on the flood inundation depth for each affected area.

Inflation adjustments were made using the Consumer Price Index (CPI) from the World Bank71 to align financial loss estimates with current values, as the original database is based on 2010 price levels. The total direct financial loss, referred to as the agency cost, was calculated by summing the loss values across each raster grid (same as DEM) within the flood domain. This agency cost was computed for all flood inundation scenarios using Eq. (3).

$${{\rm{C}}}_{{\rm{A}}}=\mathop{\sum }_{i = 1}^{n}{D}_{x(i)}\times f\left({d}_{i}\right)\times {A}_{i}$$

(3)

where CA (agency cost) represents the total economic losses due to direct damage to the roads in the study area. The variable n denotes the total number of damaged road elements, x(i) depicts the category of ith damaged road element, Dx(i) is the maximum monetary damage for the i-th road element, di represents the inundation depth of the i-th road element, and f symbolizes the proportion of the element destroyed. Ai is the affected area of ith road element.

Indirect (user) cost analysis

Road networks are also susceptible to indirect damage from floods, resulting in increased traffic congestion and heightened vehicular emissions. Traffic simulation models are commonly employed to evaluate the movement of traffic through a road network, which depends on user behavior, vehicle characteristics, traffic characteristics, etc.23. In this study, the Simulation of Urban MObility (SUMO)41,72 was utilized to model the movement of vehicles in both spatial and temporal dimensions. SUMO is based on a gap-based car following model, in which vehicles dynamically adjust their speed to avoid collisions while still trying to reach their destination. The model is also capable of modeling typical user behavior, such as lane change and calculating data such as travel time and greenhouse gas emission, and air pollutants from each simulated vehicle. The road network data extracted from OpenStreetMap (OSM) was refined using JOSM (Java OpenStreetMap Editor) to ensure accuracy in street dimensions, permissible road speeds, and traffic control regulations. Road capacities were estimated from OSM road classifications, with representative values assigned to each class: trunk roads (four lanes, 80 km/h), primary roads (two lanes, 60 km/h), secondary roads (two lanes, 50 km/h), tertiary roads (two lanes, 40 km/h), and residential roads (single lane, 30 km/h). These values were derived from standard urban traffic engineering references and adjusted for Indian urban conditions where local data were unavailable73,74,75. For this study, it was assumed that all vehicles on the road were passenger cars.

Establishing baseline traffic conditions can be achieved in two ways: by using field traffic count data or through travel demand modeling. Since traffic count data were unavailable for the study area, as the local municipality does not collect this information, we developed a travel demand model instead. This model consists of trip generation, where we created origin-destination-based traffic demand models to map commuting patterns. Traffic Assignment Zones (TAZs) were delineated based on various land-use classifications within the study area, including residential, commercial, and other categories. Trip generation for each TAZ was estimated using guidelines from the ITE Trip Generation Manual48, which provides detailed trip generation curves for estimating trip generation accounting for both peak and non-peak hour traffic. Since a local trip-generation manual is not available for Indian cities, trips were estimated using the ITE Trip Generation Manual in conjunction with local land-use characteristics. The resulting OD matrix included primarily home-based trips (work, school, recreation) along with a smaller share of pass-by trips, thereby covering all trip purposes defined in the Manual. Once trip generation was completed, trips were distributed among the TAZs using the gravity model (Eq. (4)).

$${T}_{ij}=\frac{{O}_{i}\cdot {D}_{j}}{{C}_{ij}^{\beta }}$$

(4)

where Tij represents the number of trips between origin i and destination j, Oi is the trip production at origin i, and Dj is trip attraction at destination j. the term Cij denotes the travel cost, typically based on the distance between origin i and destination j. The parameter β captures the sensitivity of trips to travel distance.

The gravity model generates the Origin-Destination (OD) matrix, which is subsequently utilized by the Dynamic User Equilibrium (DUE) model within SUMO to assign routes to individual vehicles based on real-time conditions and driver behavior. Unlike static assignment, where routes are predetermined, DUE dynamically adjusts vehicle paths in response to evolving traffic conditions76. This model considers factors such as congestion, travel time, and road capacity to continuously refine vehicle routes during the simulation, leading to more realistic representations of driver behavior. The process iterates until an equilibrium state is reached, where no vehicle can significantly reduce its travel time. Finally, the traffic simulation is executed using the routes established by the DUE model. The travel time loss and air quality impacts due to transportation were assessed, and a baseline scenario for the traffic model was generated for 72 hours, matching the duration of the flood event. To convert travel time losses into monetary terms, we multiply the time loss observed in the model by the value of travel time in Kozhikode, as characterized by income groups and trip distances77. This calculation yields the user cost associated with traffic congestion. To quantify vehicular emissions, we used HBEFA v4.2 (Handbook of Emission Factors for Road Transport) to calculate fuel consumption and emissions per vehicle based on vehicle movement. HBEFA provides emission factors for various vehicle categories under different traffic conditions78.

In the absence of real-time traffic counts, conventional methods for traffic model validation were not feasible. As an alternative, the traffic model was validated using Google Traffic Maps by visually comparing simulated traffic with typical observed congestion conditions at various locations. Additionally, 2500 stratified random sampling points were generated across the road network in the study area, and traffic speeds at these points were compared with corresponding speeds from Google Maps. The validation yielded an overall accuracy of 0.85, with a weighted F1 score of 0.854 and a kappa coefficient of 0.339, demonstrating a high level of agreement between the simulated and observed traffic conditions (Note S4 and Fig. S6).

The flood hazard data was dynamically integrated with the traffic model to accurately simulate traffic behavior during flooding events. Hourly flood propagation data were extracted from the flood hazard model for both isolated and compound flood events and then incorporated into the traffic model through rerouters, which reassign vehicles to different routes whenever a road becomes unavailable. The microsimulation assumes the same Origin-Destination (OD) matrix as the baseline scenario, without considering demand reduction during flooding. This approach isolates the impact of road network disruptions on travel delays and user costs, under the assumption that trip-making behavior remains constant during flooding events. Since OpenStreetMap (OSM) does not provide elevation data for the road network, we assigned ground surface elevation from the Digital Elevation Model (DEM) to the roads. For sections identified as bridges or overpasses, manual elevation corrections were applied to account for their elevated structure, thereby mitigating biases associated with incorrect flood detection. After that, road closures were implemented when the flood depth on the street exceeded 0.3 m, the permissible threshold for safe travel of vehicles14,43. Vehicles were dynamically rerouted based on the spatio-temporal closure of routes due to flood propagation, with rerouted vehicles taking alternative paths to reach their destinations. The travel time loss and emission measures were compared with the baseline traffic scenario to measure the indirect damage (user cost). In the microsimulation model, total trip-making demand was held constant across all scenarios, with trips canceled only when either the origin or the destination zone was directly inundated. Consequently, these trips were excluded from travel time and user cost calculations, reflecting the practical impossibility of initiating trips under inundated conditions. The user cost for each ward was calculated based on the proportion of each trip’s travel time occurring within the ward, rather than being solely associated with the trip’s origin or destination.

Expected annual cost analysis

The expected annual cost (EAC) for isolated events-coastal, fluvial, and pluvial floods-was calculated by multiplying the damage associated with each event by their respective occurrence probabilities for baseline, 50-year, and 100-year return periods (Eq. (5)).

For compound flood events, we estimated the EAC by first determining the joint probability distribution of extreme rainfall, tidal surges, and river discharge using a trivariate Gumble copula79,80,81 (Eq. (6)). This copula effectively captures the dependencies between the three variables, providing a robust framework for joint probability estimation.

$$\begin{array}{lll}{P}_{{\text{baseline}}(i)} & \times & {C}_{{\text{baseline}}(i)}\\{\text{EAC}}_{(i)}= &+&{P}_{{50{\text{yr}}}(i)}\times {C}_{{50{\text{yr}}}(i)}\quad i\in \{{\text{Coastal}},\, {\text{Fluvial}}, {\text{Pluvial}}\}\\ &+&{P}_{{100{\text{yr}}}(i)}\times {C}_{{100{\text{yr}}}(i)}\end{array}$$

(5)

Where EAC(i) represents the expected annual cost for coastal (C), fluvial (F), and pluvial (P) flooding events. The variable Pbaseline(i) represents the probability of a baseline flood event occurring, while Cbaseline(i) corresponds to the cost associated with the baseline flood event for the specific type of flood event i, where i is Coastal, Fluvial, or Pluvial. Similarly, P50yr(i) and C50yr(i) represent the probability and associated cost for a 50-year flood event, and P100yr(i) and C100yr(i) are the probability and associated cost for a 100-year flood event.

The Gumbel copula for the three types of flooding can be expressed as:

$$\begin{array}{rcl}{C}_{\theta }({u}_{{\rm{coastal}}},{u}_{{\rm{fluvial}}},{u}_{{\rm{pluvial}}})&=&\left[{\left(-\ln ({u}_{{\rm{coastal}}})\right)}^{\theta }+{\left(-\ln ({u}_{{\rm{fluvial}}})\right)}^{\theta }\right.\\ &&{\left.+{\left(-\ln ({u}_{{\rm{pluvial}}})\right)}^{\theta }\right]}^{\frac{1}{\theta }}\end{array}$$

(6)

Where The uniform random variables ucoastal, ufluvial, upluvial represent the marginal distributions of the coastal, fluvial, and pluvial floods, respectively. The parameter θ is known as the dependence parameter of the Gumbel copula, and it indicates the strength of upper-tail dependence between these flooding events. A higher value of θ signifies a stronger dependence between extreme flood events in coastal, fluvial, and pluvial areas. The copula function Cθ(ucoastal, ufluvial, upluvial) is used to capture the joint dependence structure among the coastal, fluvial, and pluvial flood events, thus modeling their combined risks.

The resultant probabilities for the baseline, 50-year, and 100-year scenarios were multiplied by the corresponding compound flood damages to estimate the Expected Annual Cost (EAC) for the compound flood event (Eq. (5). This EAC takes into account the dependence between the three flooding types, namely coastal, fluvial, and pluvial floods.

The EAC is further categorized into direct damage (agency cost) and indirect damage (user cost) for all scenarios, including both isolated and compound events. These damages are quantified in monetary terms. Additionally, the EAC related to vehicular emissions is expressed in tonnes. The GHG emissions are further broken down into specific components, including CO2, CO, PMx, and NOx, providing a detailed assessment of the environmental impact associated with flood events.