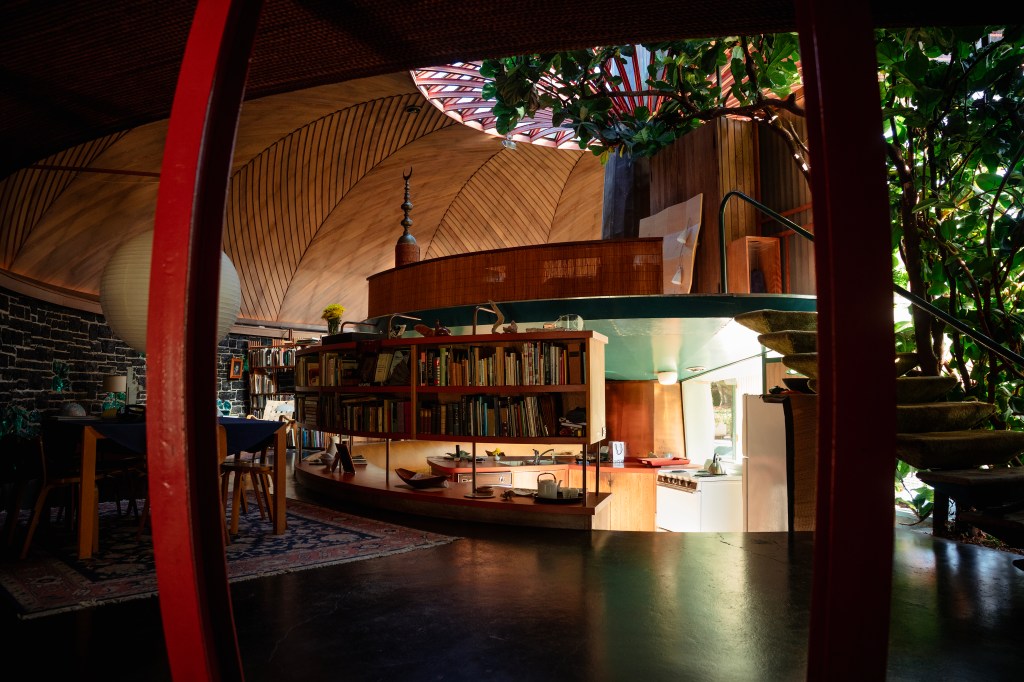

People who saw the strangely shaped house being built in Aurora — its red curved steel ribs, a black coal wall dotted with marbles and glass cullet — had different names for it, Life magazine reported in 1951. Some called it a “birdcage.” “Big apple.” “Dome.” “Hangar.”

Their comments were enough for its owners, Chicago Academy of Fine Arts director Ruth Van Sickle Ford and her husband, Albert, to put a sign outside that read: “We don’t like your house either.”

Nearly eight decades after it was built, the Ford House continues to be one of the best examples of the ingenuity that sprang from the mind of architect Bruce Goff — and the mixed reaction that creative wellspring could elicit.

The Kansas native has been called an “outsider” and a “rebel,” the best architect the public’s never heard of, a master of organic architecture and a prodigious talent whose relentless desire to never copy himself or anyone else is one reason he’s often not mentioned in the same breath as Frank Lloyd Wright, Louis Sullivan or Ludwig Mies van der Rohe.

Goff designed more than 500 buildings in a career that started at 12 and ended with his death 66 years later. Most were set in middle America. The Ford House is one of eight he built in Illinois, including two in Chicago, where pre-World War II, he established a private practice in Rogers Park and taught at Ford’s academy.

Goff’s eclectic designs — at times angular, curvy, futuristic, Seussian — and innovative use of nontraditional embellishments — glass ashtrays, feathers, sequins, coal — mirror the kinds of quirky attractions that have become synonymous with Route 66. (Architectural historian and writer Charles Jencks once dubbed him “the Michelangelo of kitsch,” a description Goff reportedly bristled at.)

And like the famed roadway, which celebrates its centennial next year, Goff is in the midst of a cultural resurgence of sorts.

In 2018, T: The New York Times Style Magazine profiled Goff in an article titled, “The Man Who Made Wildly Imaginative, Gloriously Disobedient Buildings.” Three years later, the city where he got his start in architecture, Tulsa, Oklahoma, played host to the first of what’s become an annual celebration called Goff Fest, co-created by a local filmmaker whose documentary about his life and work is scheduled for a wider release this winter.

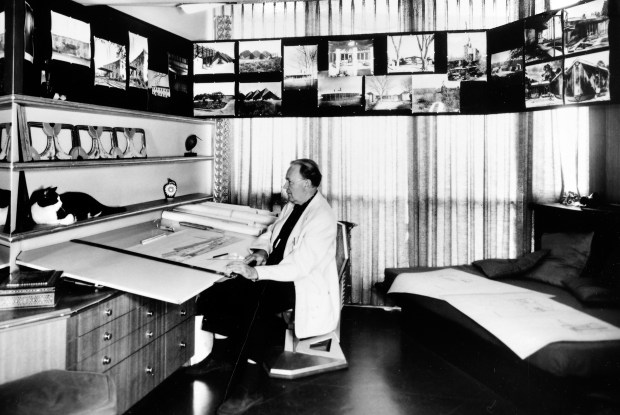

A 1962 photograph shows architect Bruce Goff in his studio with his cat, Chiaroscuro. Goff was daringly inventive and often used unconventional materials in designs. (Art Institute of Chicago)

A 1962 photograph shows architect Bruce Goff in his studio with his cat, Chiaroscuro. Goff was daringly inventive and often used unconventional materials in designs. (Art Institute of Chicago)

Starting in December, the Art Institute of Chicago will hold an exhibition titled “Bruce Goff: Material Worlds,” which will feature more than 200 of his drawings, models and paintings taken from the museum’s extensive Goff collection and archive, donated in 1990, eight years after his death.

One of the show’s goals is to introduce Goff to the broader public, co-curator Alison Fisher said.

“He just really isn’t in the mainstream of most people’s architectural history education, and the people I know who’ve heard of him just had a really enterprising professor who loved him,” she said. “So, I think we’re really excited about trying to bring him more into the canon, because without people like Goff, the profile looks pretty flat for midcentury architecture.”

‘Out in the hinterland’

Goff was born in 1904 in Alton, Kansas, a tiny town in the north-central part of the state. His family eventually settled in Tulsa, where he took inspiration from the natural world and the Native American tribes who lived there.

“When you’re out in the hinterland, as they say, you’re not supposed to have any culture,” he told a British Broadcasting Corporation television crew in 1981, a year before his death. “And there isn’t a whole lot of it around except what’s native to the area.”

He described his entry to architecture as an accident. “I had never heard of the word architecture or the word architect,” he told the BBC. His family saw Goff had artistic talent in the homes, castles and cathedrals the boy drew on scraps of wallpaper or wrapping paper.

One day, he said, his father came home — having “had a little too much to drink” — and told him to put on his hat and coat. They went to East Fourth Street and South Main Street in the heart of Tulsa’s downtown. Goff’s father stopped a stranger and asked, who’s the best architect in town?

Rush, Endacott & Rush, the man answered. Goff and his father walked to the firm’s office, where his dad requested they make him into an architect.

The Guaranty Laundry building on 11th Street, Route 66, in Tulsa, Oklahoma, on June 17 2025, which is now the Page Storage warehouse. It was designed by Bruce Goff in 1928 when he worked with the firm Rush, Endacott & Rush. (E. Jason Wambsgans/Chicago Tribune)

The Guaranty Laundry building on 11th Street, Route 66, in Tulsa, Oklahoma, on June 17 2025, which is now the Page Storage warehouse. It was designed by Bruce Goff in 1928 when he worked with the firm Rush, Endacott & Rush. (E. Jason Wambsgans/Chicago Tribune)

Goff started as an apprentice. Two years later, he was designing homes. His early drawings were compared to Wright, though he was unfamiliar with the famed architect and his work. He would eventually correspond with Wright and another of his heroes, Sullivan, once writing both men to ask whether he should pursue a formal education in architecture.

In response, Sullivan told him he’d spent his life trying to live down the education Goff was considering. Wright’s reply was shorter: “If you want to lose Bruce Goff, go to school.”

He took their advice, opting instead to continue learning on the job.

The restored Adah Robinson House, designed by architect Bruce Goff, in Tulsa, Oklahoma, on June 16, 2025. (E. Jason Wambsgans/Chicago Tribune)

The restored Adah Robinson House, designed by architect Bruce Goff in Tulsa, Oklahoma, on June 16, 2025. (E. Jason Wambsgans/Chicago Tribune)

The restored Adah Robinson House, designed by architect Bruce Goff, in Tulsa, Oklahoma, on June 16, 2025. (E. Jason Wambsgans/Chicago Tribune)

The restored Adah Robinson House, designed by architect Bruce Goff, in Tulsa, Oklahoma, on June 16 2025. (E. Jason Wambsgans/Chicago Tribune)

Show Caption

1 of 4

The restored Adah Robinson House, designed by architect Bruce Goff, in Tulsa, Oklahoma, on June 16, 2025. (E. Jason Wambsgans/Chicago Tribune)

Goff is credited with at least a dozen buildings in Tulsa during the 1920s. In 1925, he designed a home and studio for his high school art teacher, Adah Robinson, steps from Route 66. The studio includes what’s said to be among the first uses of a sunken conversation pit. “I just think Bruce was wildly ahead of the game and just a true master at his craft,” said Justice Quinn, a Tulsa-based interior designer who in recent years helped restore the studio.

Around the same time her studio was being built, Robinson had been asked by friends at the Boston Avenue United Methodist Church in Tulsa to design a new building. She suggested the church hire Rush, Endacott & Rush and its young architect, Goff, to assist with the plans.

Boston Avenue United Methodist Church by Bruce Goff in Tulsa, June 16, 2025. (E. Jason Wambsgans/Chicago Tribune)

Boston Avenue United Methodist Church by Bruce Goff in Tulsa, June 16, 2025. (E. Jason Wambsgans/Chicago Tribune)

Boston Avenue United Methodist Church by Bruce Goff in Tulsa, June 14, 2025. (E. Jason Wambsgans/Chicago Tribune)

Boston Avenue United Methodist Church by Bruce Goff in Tulsa, June 16, 2025. (E. Jason Wambsgans/Chicago Tribune)

Boston Avenue United Methodist Church by Bruce Goff in Tulsa, June 14, 2025. (E. Jason Wambsgans/Chicago Tribune)

Boston Avenue United Methodist Church by Bruce Goff in Tulsa, June 16, 2025. (E. Jason Wambsgans/Chicago Tribune)

Boston Avenue United Methodist Church by Bruce Goff in Tulsa, June 16, 2025. (E. Jason Wambsgans/Chicago Tribune)

Boston Avenue United Methodist Church by Bruce Goff in Tulsa, June 14, 2025. (E. Jason Wambsgans/Chicago Tribune)

Bruce Goff’s drawing of his Boston Avenue Methodist-Episcopal Church in Tulsa, Oklahoma. (Ryerson and Burnham Art and Architecture Archives, Bruce Goff Archive/Art Institute of Chicago)

Show Caption

1 of 9

Boston Avenue United Methodist Church by Bruce Goff in Tulsa, June 16, 2025. (E. Jason Wambsgans/Chicago Tribune)

Part Gothic cathedral, part art deco skyscraper, the church features a striking central tower of vertical windows between columns of Indiana limestone that rises 250 feet to a spire of glass and copper sculpted to evoke hands raised in prayer.

With a semicircle sanctuary inspired by Sullivan’s design for a Methodist church in Iowa, the Tulsa church was hailed by author and critic Sheldon Cheney as “the most provocative American example of different church building.”

Adah Robinson, Bruce Goff’s art teacher, who the Boston Avenue United Methodist Church by Goff in Tulsa credits with the design of the church, on June 14, 2025. Her portrait hangs prominently in its center hall. (E. Jason Wambsgans/Chicago Tribune)

Adah Robinson, Bruce Goff’s art teacher, who the Boston Avenue United Methodist Church by Goff in Tulsa credits with the design of the church, on June 14, 2025. Her portrait hangs prominently in its center hall. (E. Jason Wambsgans/Chicago Tribune)

For Robinson and Goff, it should have been cause for celebration. Instead, it apparently caused a bitter rift between the two over who was responsible for its creation. The church credits Robinson as its designer; her portrait hangs prominently in its center hall. Goff’s close friend and fellow architect Bart Prince says the building is clearly Goff’s.

“He was shocked by it,” Prince said of Goff’s reaction to the controversy. “He felt he was really being cheated.”

Tulsa Club, designed by architect Bruce Goff and built in 1927, on June 16 2025. (E. Jason Wambsgans/Chicago Tribune)

Tulsa Club, designed by architect Bruce Goff and built in 1927, on June 16 2025. (E. Jason Wambsgans/Chicago Tribune)

Tulsa Club, designed by architect Bruce Goff, was built in 1927, on June 16 2025. (E. Jason Wambsgans/Chicago Tribune)

Riverside Studio theater, built in 1928, was designed by Bruce Goff for his piano teacher, Patti Adams Shriner, in Tulsa, Oklahoma. (E. Jason Wambsgans/Chicago Tribune)

Riverside Studio theater in Tulsa, Oklahoma, on June 16, 2025. It was built in 1928 and designed by Bruce Goff for his piano teacher, Patti Adams Shriner. (E. Jason Wambsgans/Chicago Tribune)

Show Caption

1 of 5

Tulsa Club, designed by architect Bruce Goff and built in 1927, on June 16 2025. (E. Jason Wambsgans/Chicago Tribune)

Expand

‘The champion of the everyday’

Flush with oil money, the 1920s were a boom time for Tulsa. Then the stock market crashed, and the country plunged into the Great Depression. Hundreds of thousands of Dust Bowl refugees fled Oklahoma on Route 66, heading west for California and the promise of work on farms so fertile, it was said, that fruit fell from the trees.

Goff, true to form, did not follow the trend. Instead, he moved to Chicago in 1934. He first worked with artist, sculptor and designer Alfonso Ianelli, then at the Libbey-Owens-Ford glass company (he designed their Chicago showroom) and as a teacher at Ruth Ford’s fine arts academy.

The home Bruce Goff designed for Chicago artist Charles Turzak in the Edison Park neighborhood, on Oct. 22, 2025. (E. Jason Wambsgans/Chicago Tribune)

The home Bruce Goff designed for Chicago artist Charles Turzak in the Edison Park neighborhood, on Oct. 22, 2025. (E. Jason Wambsgans/Chicago Tribune)

In 1948 Bruce Goff remodeled an existing wood house from 1889 in the Uptown neighborhood into a home and recording studio for recording engineer Myron Bachman. Shown Oct. 22, 2025. (E. Jason Wambsgans/Chicago Tribune)

In 1948 Bruce Goff remodeled an existing wood house from 1889 in the Uptown neighborhood into a home and recording studio for recording engineer Myron Bachman. Shown Oct. 22, 2025. (E. Jason Wambsgans/Chicago Tribune)

He designed homes in suburban Park Ridge and Glenview and in Chicago’s Edison Park neighborhood. That home, built for artist Charles Turzak, is one of two Goff homes in the city. The other, for recording engineer Myron Bachman, is in Uptown and boasts sheets of corrugated aluminum angled to evoke a prism.

“Goff is really the champion of the everyday,” Fisher said. “A lot of times, architecture is seen as something that’s for the elite.” But Goff, she continued, “just was picking materials that were so commonplace. A lot of things he actually just got at five-and-dime shops, and he built at every single price point. He built houses that are super simple and then things that are extremely luxurious. And so that makes him different. He listened to his clients.”

Goff remained in Chicago until the onset of World War II, when he enlisted in the U.S. Navy’s construction force, the Seabees. He stayed in California briefly after the war and then returned to Oklahoma. In 1947, with only a high school education, he took a faculty job at the University of Oklahoma’s architecture department. A year later, he was named department chair. Quickly, he raised the school’s national and international reputation.

He did the same with his own profile, producing a staggering collection of homes that many consider to be among the best in his career.

The John Frank House on June 14, 2025, near Route 66 in Sapulpa, Oklahoma. It was built in 1955 and designed by architect Bruce Goff for John Frank, founder of Frankoma Pottery. (E. Jason Wambsgans/Chicago Tribune)

The John Frank House on June 14, 2025, near Route 66 in Sapulpa, Oklahoma. It was built in 1955 and designed by architect Bruce Goff for John Frank, founder of Frankoma Pottery. (E. Jason Wambsgans/Chicago Tribune)

The John Frank House on June 14, 2025, near Route 66 in Sapulpa, Oklahoma. It was built in 1955 and designed by architect Bruce Goff for John Frank, founder of Frankoma Pottery. (E. Jason Wambsgans/Chicago Tribune)

The John Frank House on June 14, 2025, near Route 66 in Sapulpa, Oklahoma. It was built in 1955 and designed by architect Bruce Goff for John Frank, founder of Frankoma Pottery. (E. Jason Wambsgans/Chicago Tribune)

The John Frank House on June 14, 2025, near Route 66 in Sapulpa, Oklahoma. It was built in 1955 and designed by architect Bruce Goff for John Frank, founder of Frankoma Pottery. (E. Jason Wambsgans/Chicago Tribune)

Show Caption

1 of 5

The John Frank House on June 14, 2025, near Route 66 in Sapulpa, Oklahoma. It was built in 1955 and designed by architect Bruce Goff for John Frank, founder of Frankoma Pottery. (E. Jason Wambsgans/Chicago Tribune)

Goff’s work caught the attention of the venerable Life magazine. A 1948 story titled “Consternation and Bewilderment in Oklahoma” mentions that a crowd of 14,500 people gathered to look at a home he built in Norman for the Ledbetter family.

Three years later, Life profiled the Ford House in Aurora, and began with the line: “Architect Bruce Goff, one of the few U.S. architects whom Frank Lloyd Wright considers creative, scorns houses that are ‘boxes with little holes.’”

Another Life article in 1955 featured the Goff-designed Bavinger House, also in Norman. Instead of rooms, it featured saucer-like suspended platforms. The roof spirals like a helix around a central mast to which it is connected with cables.

Bruce Goff’s Eugene and Nancy Bavinger House in Norman, Oklahoma, was razed in 2016. (Art Institute of Chicago)

Bruce Goff’s Eugene and Nancy Bavinger House in Norman, Oklahoma, was razed in 2016. (Art Institute of Chicago)

“In architecture now, it’s very easy to copy and paste these easy and cheap buildings, and unfortunately, a lot of the cities in the U.S. are being built into these box-like structures,” said Britni Harris, Goff Fest co-founder and director of the documentary “GOFF.” “And I think that Bruce Goff was not only an architect, he was an artist. He thought about your environment and how that impacts you. I think that he wanted people to grow and be inspired in his buildings.”

The Bavinger House is gone, razed in 2016. Another iconic Goff home, Shin’en Kan in Bartlesville, Oklahoma, was destroyed in a 1996 fire.

A photograph of architect Bruce Goff inside the Ford House, designed by Goff in Aurora and built in 1949–50. (E. Jason Wambsgans/Chicago Tribune)

A photograph of architect Bruce Goff inside the Ford House, designed by Goff in Aurora and built in 1949–50. (E. Jason Wambsgans/Chicago Tribune)

The Ford House, meanwhile, still stands. In 2019, its owner, architect and professor Sidney K. Robinson, received a stewardship award from the nonprofit Landmarks Illinois for his restoration and preservation of the house. Two years later, Robinson shared his thoughts on the home, and Goff, with the nonprofit MAS Context:

“I was one of those doubters having known about Goff’s architecture only through photographs. In the two-dimensional representation, patterns and textures and colors collided. It was just too much, excessive to the point of vulgarity. But now having lived in a Goff house for thirty years—what happened? I have visited a number of Goff buildings and the Ford House is the only one I would want to live in. Walking into this locally notorious house on an August Saturday morning in 1986 instantly overcame my previous doubts. As I have remarked before: like Saul on the road to Damascus, I was changed! What did I see in that flash of discovery? I saw intense sensory stimulation and clear order at the same time. As I have come to understand, this house is simultaneously exciting and calming. That is extraordinary.”

‘All parts of the story’

The six-paragraph story ran on Page 22 of The Tulsa Tribune’s Nov. 29, 1955, edition, under the headline: “Bruce Goff, Ex-Tulsan, Quits OU’s School of Architecture.”

His resignation, the article reads, was due to “poor health,” which made it “impossible to carry on his private practice as an architect and his university work.”

Days later, new details surfaced. He had been charged with a misdemeanor count of contributing to the delinquency of a minor. News reports at the time quote a criminal complaint alleging that Goff, while on campus, “caused a (14-year-old) boy ‘to expose his person in a private place in such a manner as to be offensive to decency’ and ‘did excite vicious and lewd thoughts’ in the boy’s mind.” He initially pleaded not guilty but eventually switched it to guilty and was fined $500.

Goff, who was gay, did not hide his sexuality. But it wasn’t something he widely discussed either.

“He was kind of a quiet, ordinary person,” Prince said. “People have written articles saying he was flamboyant. That just wasn’t true. He would wear a loud shirt occasionally and somehow they think that means flamboyant. He was quiet. He was very conservative.”

A prevailing narrative around his departure from OU is that the allegation against him was likely false, the result of him being a gay man in the 1950s in a deeply conservative state.

Even now, Goff’s personal life can be a thorny subject.

“When you talk about those things, there are some people in the architecture world who are like, what’s private is private, we should only talk about the work,” said Goff Fest co-creator Karl Jones. “And part of it is the closet. Part of it’s determinism — we don’t want to relegate him to being a gay architect. I understand it all. But I just think we can be post-determinist and post-queer and celebrate all parts of the story.”

‘They couldn’t understand it’

In the fall of 1968, Arizona State University asked Goff to speak to architecture students. Several faculty members were upset at the invitation. They vowed not to attend and encouraged students to do the same.

One of those students was 21-year-old Bart Prince.

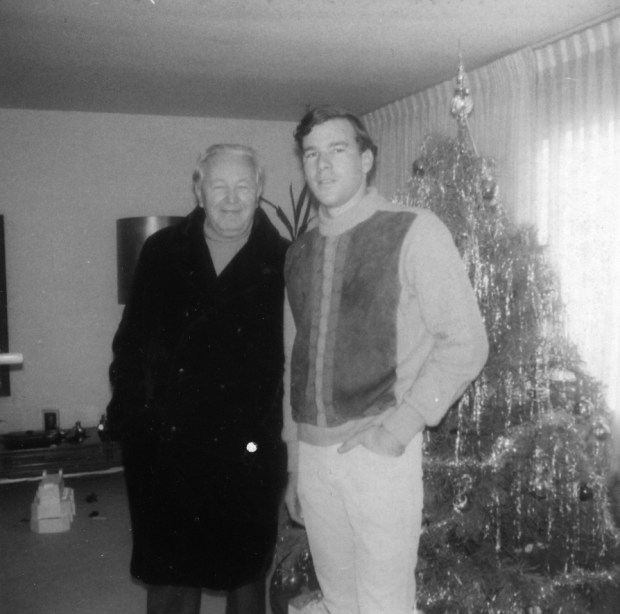

Bruce Goff, left, and Bart Prince at Prince’s parents’ house in Albuquerque, New Mexico, just before Christmas in December 1969. The two architects and friends were heading to Chicago on Route 66 later that day. (Bart Prince photo)

Bruce Goff, left, and Bart Prince at Prince’s parents’ house in Albuquerque, New Mexico, just before Christmas in December 1969. The two architects and friends were heading to Chicago on Route 66 later that day. (Bart Prince photo)

Prince remembered how one instructor took him aside and told him he should skip Goff’s lecture, that it would be nothing the young student would want to see.

“Goff’s work was really controversial anyway, but especially in the schools because a lot of them thought: It isn’t architecture. It isn’t serious,” said Prince, 78. “They couldn’t understand it … to them, Goff’s work was just kind of fantasy. I never quite understood … because to me, it was really beautiful work.”

Architect Bart Prince, a close friend of Bruce Goff, in his studio in Albuquerque, New Mexico, on Oct. 17, 2025. (E. Jason Wambsgans/Chicago Tribune)

Bart Prince residence and studio on Oct. 17, 2025, that he designed in 1984 in Albuquerque, New Mexico. (E. Jason Wambsgans/Chicago Tribune)

Show Caption

1 of 2

Architect Bart Prince, a close friend of Bruce Goff, in his studio in Albuquerque, New Mexico, on Oct. 17, 2025. (E. Jason Wambsgans/Chicago Tribune)

Defiantly undeterred, Prince attended Goff’s speech. By then, the 64-year-old had weathered the scandal of his resignation and criminal case and continued his prolific output of home designs. After OU, he moved to Bartlesville and opened an office in Price Tower, the only skyscraper built by Wright — Goff was originally asked to design the building, Prince said, but being too busy, suggested Wright take the job instead. He then relocated to Kansas City before eventually settling in Tyler, Texas.

Prince and Goff became fast friends. “He was very low key,” Prince said. “His voice was low. He walked like a cat, padding along.”

Prince spoke fondly of Goff’s humor and love of puns, how he discreetly stashed raw fish in his pocket at a sushi restaurant in Japan so as to not offend the staff by refusing to eat it, or how he initially rejected television until his mother got him hooked on it, and then he took to carrying around a TV Guide in his pocket so he wouldn’t miss an episode of “Star Trek.”

Bruce Goff’s Glen Luetta Harder House, Mountain Lake, Minnesota. (Julius Shulman photography archive/Getty Research Institute/Art Institute of Chicago)

Bruce Goff’s Glen Luetta Harder House, Mountain Lake, Minnesota. (Julius Shulman photography archive/Getty Research Institute/Art Institute of Chicago)

The pair’s friendship turned to collaboration. Prince did drawings for a Goff-designed home for the Harder family, turkey farmers in southwestern Minnesota. Built in 1970, the home featured a trio of chimneys made of local boulders and a roof covered in bright-orange outdoor carpeting.

The Bruce Goff-designed Pavilion for Japanese Art at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, on Oct. 10, 2025. (E. Jason Wambsgans/Chicago Tribune)

The Bruce Goff-designed Pavilion for Japanese Art at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, on Oct. 10, 2025. (E. Jason Wambsgans/Chicago Tribune)

“A lot of architects seem to try to get around what their clients want,” Prince said. “They think their clients don’t know. Goff was the other way. He never went to try to get a client, which makes him different than a lot of architects. They had to seek him out. He wanted to know about the site, what they liked, what they didn’t like, and then he worked from there (and) developed a design specifically for them. That was the case in every case. So when he talked about his work, each building represented a client for him.”

Goff died on Aug. 4, 1982, in Tyler. Two posthumous projects he designed, the Los Angeles County Museum of Art’s Pavilion for Japanese Art and the Al Struckus House in LA, were completed by Prince.

Architect Bruce Goff’s grave in Graceland Cemetery in Chicago, Aug. 27, 2025. (E. Jason Wambsgans/Chicago Tribune)

Architect Bruce Goff’s grave in Graceland Cemetery in Chicago, Aug. 27, 2025. (E. Jason Wambsgans/Chicago Tribune)

Show Caption

1 of 2

Architect Bruce Goff’s grave in Graceland Cemetery in Chicago, Aug. 27, 2025. (E. Jason Wambsgans/Chicago Tribune)

His cremains were interred at Chicago’s Graceland Cemetery, the final resting place of architectural giants Louis Sullivan, John Root, Daniel Burnham and Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, whose simple black granite rectangular marker is in the plot adjacent to Goff.

Goff’s headstone, with its rounded pyramid shape and single chunk of glass cullet — salvaged from Shin’en Kan — looks like none of the others.