No one is more excited than Anna Johnson about the arrival in the Bay Area of the WNBA’s newest expansion team, the Golden State Valkyries. “Oh, I wonder what it’s gonna be like that first day!” she said with a laugh a few months ago, referring to Tuesday’s preseason home opener at San Francisco’s Chase Center. “I’m already fussing at the people about my tickets on my phone.”

But Johnson, 70, who is both a Valkyries season ticket holder and a lifelong Oakland resident, is not just any eager fan. She is the first professional women’s basketball player from the bay, having suited up for the San Francisco Pioneers of the short-lived Women’s Professional Basketball League. This was 1979, long before the dawn of the WNBA in 1996.

Her story is little known, as is that of the Pioneers. Her career and the team itself came to an abrupt close, the franchise shutting down so quickly that, to this day, Johnson and her teammates lament that they never got a chance to say goodbye to their fans. But maybe, they hope, they will receive some recognition amid the hoopla surrounding the Valkyries’ inaugural season.

Johnson, typically humble if not quiet about her achievements, has been energized to do a little more politicking on behalf of her old team’s legacy. When she was purchasing season tickets, the Valkyries sales rep on the phone told Johnson he was new to the WNBA. She told him about the Pioneers, explaining that they were the first women’s pro team in town. The young man seemed genuinely intrigued. So Johnson continued. “We’re the unknown,” she told him. “Let me give you some knowledge.”

Growing up in the 1960s and 1970s in Oakland was a “unique and formative backdrop” for her basketball journey, Johnson said. But the story really begins with her mother, Ruth.

Ruth Johnson was a force. She raised her four children in North and East Oakland in the 1960s, telling them: “To make your mark on life, you have to have an education.” So while Johnson’s older brothers and cousin often left her out of pickup games at Bushrod Park, she became a dedicated student who learned the game while attending Claremont Middle School. These were the final years preceding Title IX, when girls were restricted to playing “rover ball,” with three players from a team on offense and the other three across the court on defense.

Anna Johnson at Oakland Tech’s Hall of Honor ceremony in February. Credit: Maya Goldberg-Safir

Anna Johnson at Oakland Tech’s Hall of Honor ceremony in February. Credit: Maya Goldberg-Safir

“I was one of the few lucky ones who got to cross to the other side,” Johnson said with a smile. “Offense and defense.”

The rules around girls basketball were changing quickly. By the time Johnson was in 8th grade, Claremont’s coach, Lola Smith, had players competing five-on-five. She’d also found a way to hold practices twice a week inside the Mormon Temple, in the foothills of East Oakland. “I don’t know how,” said Johnson, “but Coach had the hookup.” Training was serious work. The girls practiced shooting from trampolines to stabilize their balance. “I thought, this woman is trying to kill me,” Johnson said.

The truth is that her coach made Johnson fall in love with basketball. By high school, she fully committed to the game, becoming a star at Oakland Tech. There, she played under Marva Eickelberger, known as Coach E, a strict disciplinarian. Johnson developed a sweet turnaround jump shot, light and quick, and a knack for tenacious defense.

In 1972, the same year Title IX was signed into law, prohibiting sex discrimination in education programs, Johnson took her skills to Cal State Hayward, but she was hungry for more. “I always wanted to play against different competition, instead of playing against the same person,” said Johnson. “There’s always someone else that’s better than you, playing harder than you. So you go out and play.”

Johnson was relentless about getting out there. She drove around the bay searching for talent, playing in pickup games with women and men at Berkeley Rec Center, Merritt College, “the legendary Mosswood,” Hamilton Park in San Francisco, the gym at San Francisco State University — anywhere she could find a run. “I played everywhere,” she said. At 5-foot-10, Johnson was known for her explosive first step, badgering slower defenders into fouling her on the way to the hoop. “I kept coming at you because you were gonna foul me eventually,” she said. “That’s probably why my back and everything else hurts to this day.”

Beset by a sleepy Bay Area basketball scene and a lack of women mentors, Johnson faced an uphill battle. But Los Angeles was different. “Down there it was basketball,” she recalled. Johnson met a pair of twins playing for San Francisco State who invited her to live at their family’s home in Pasadena for summer basketball. She was elated.

The only problem was that Johnson had no friends or family in LA. “Where you gonna stay? Who you know down there?” her mother Ruth demanded to know. Finally Johnson got the twins’ mother on the phone. “The mom-to-mom talk was what made it happen,” she said. Eventually, Ruth flew south with her daughter for the AAU tryouts. “That’s how I knew my mother loved me,” said Johnson. Both mother and daughter could see the vision of Johnson playing ball at a higher level. What would’ve been unthinkable just a few years earlier was now, in the explosion of opportunities afforded by Title IX, suddenly plausible.

The LA scene was a new world. Johnson competed in AAU and pro-am leagues alongside some of the very best women’s players of her generation: Ann Meyers, Cardte Hicks, Kim Bueltel, Anita Ortega, Musiette McKinney. She won back-to-back AAU national championships with a team called “Anna’s Bananas” (named after the young daughter of their coach), which the New York Times referred to as “a team of California women who look as if they just came in from surfing.” Soon, Johnson earned a partial scholarship to play basketball at Long Beach State — not a lot of scholarships were given out in those early days of Title IX — and in 1978 she completed her degree.

Despite a successful career at Long Beach, Johnson was running out of options to keep playing basketball competitively. She spent her days working at a mental health rehabilitation home in North Oakland. And yet she was determined to continue her career. “I was trying to figure out: Who could I play for?”

“A team of California women who look as if they just came in from surfing,” said New York Times. Credit: Courtesy Anna Johnson

“A team of California women who look as if they just came in from surfing,” said New York Times. Credit: Courtesy Anna Johnson

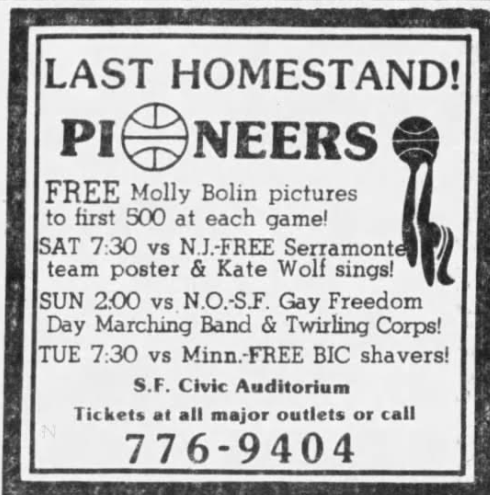

At that moment, San Francisco became the latest city to join the newly formed Women’s Professional Basketball League. The WBL was an upstart league created by an Ohio man named Bill Byrne, a hustling entrepreneur chasing financial promise in the future of women’s sports. The league, which lasted only three seasons between 1978-1981, was a rollercoaster of emotions for players who both achieved the dream of playing in a pro league while also enduring financial instability and at times prejudicial treatment.

Some of Johnson’s former teammates from LA were drafted, but not her, and neither did she get a call from the league. That didn’t stop her. In the fall of 1979, Johnson drove over the Bay Bridge in her Chevy Mazda hatchback for the first tryout hosted by the Pioneers.

At the tryout, Johnson recognized many of the players from the local basketball scene. But as the group kept scrimmaging, the number of women present kept dwindling. Johnson was determined to make her mark, who cared if her shot was off that day. She attacked the ball, getting even more physical, playing up her ferocious defensive style. “My defense was what kind of reeled them in,” she recalled.

It worked. Johnson was selected as a walk-on for the 1979-80 roster, besting at least 35 other women trying out for just two spots. She was the only member of the Pioneers born and raised in the Bay Area.

For their first home game at San Francisco Civic Auditorium, the Pioneers lined up as their star center, Hicks, sang the national anthem.

Then, under the bright lights, their names were called out one-by-one. As Johnson’s name was announced, she waved proudly in her blue and yellow Pioneers uniform, rocking an afro that made her seem at least an inch taller. Johnson’s friends and family from Oakland were scattered around the arena, hollering and cheering. “My P.E. teacher, a couple coaches, friends, neighborhood kids — they all came out,” she said. That night, Johnson signed autographs with her teammates, blown away by the thousands of spectators.

Johnson’s time on the Pioneers may have been short lived that season, but even from the bench she embodied the mentality of “don’t get ready, stay ready.” She was constantly studying opponents’ moves, analyzing the game, and impacting play any time she got the opportunity. Her teammates also remember Johnson as essential. “When I think of Anna, I think of one of the leaders of the Pioneers game,” said Hicks. “She was a strong presence.”

Johnson became something of a local guide, too. She’d send players down to Fisherman’s Wharf for chowder. She took her best friend “Moose” McKinney to get Mrs. Fields cookies. “We met Debbi Fields!” McKinney said, still swooning. The whole team got along superbly, trading off between barbecues together and brutal four-hour practices. One underappreciated aspect of women’s professional basketball is that play can get rough when the roster spots are scarce. “It was like, I wasn’t going to help you up,” Johnson said. McKinney agreed “We were professional athletes,” she said. “So you better be serious.”

Credit: Courtesy Molly Kazmer

Credit: Courtesy Molly Kazmer

Over two seasons, the Pioneers went 32-40, making it to the semifinals against the New York Stars in 1980, around the time that Johnson got cut from the team. McKinney would call her friend up, telling her, “You need to be here!” But whatever sisterhood had developed among the Pioneers, their time together would soon be cut short.

The WBL had struggled financially since its inception. At the end of the 1981 season, owner Marshall Geller gathered the Pioneers for a final dinner. There, he announced that this was the last time they’d ever be together in one room. The team was folding. Soon, the league followed. Players scattered with the WBL’s shuttering, unable to say farewell even to their loyal fans. Many of the players, like Johnson, Hicks, and McKinney, still mourn that fact to this day.

Like many others in the WBL, Johnson reached both the pinnacle of her playing career in the league and its conclusion. While nearly all of her Pioneers teammates left the Bay Area, Johnson made the conscious decision to stay in Oakland. She would do for others what Coach Smith had done for her. She vowed to “pay it forward” by reinvesting her knowledge of the game in the next generations.

On February 7, the atmosphere inside Oakland Tech’s gymnasium was electric. It was the school’s annual hall of fame ceremony, and girls varsity head coach Leroy Hurt had to quiet the crowd when he took the microphone. “All right,” he said. “Please welcome a young lady named Anna Johnson!”

Johnson strode to center court, at ease, while the crowded room burst into applause. The septuagenarian still carries herself with the energy of a former athlete, someone who wakes up at the crack of dawn to work out regularly. On this night, Johnson would become the newest member of Oakland Tech’s Hall of Honor. Perhaps more importantly, her history with the school was being joined to the present-day success of Tech, a powerhouse in the girls high school basketball scene in part thanks to the work of Johnson herself.

By the time the WBL collapsed in 1981, Johnson was working as a coach. Soon, she took over the team at Tech, where she led the program between 1982-88. Her goal was to fundamentally change the girls basketball program.

As a head coach, Johnson shaped the program in her image. Tech’s primary weapon was its quickness and tough-as-hell defense. She introduced a full-court press and delighted audiences with the fast pace. “I was trying to bring it up and make it more innovative so people would come and watch,” Johnson said. “Did they watch? Yes. Did they like the game? Yes.”

The team’s overall record improved, while at the same time, Johnson challenged her players personally. “We practice on all our weaknesses,” she told them. She emphasized intentionality, camaraderie, and the importance of channeling anger into productive energy. Johnson could see the bigger picture for her players, and for the future of women’s basketball.

“Coach Johnson, this is her house. I want everybody to know that she laid the foundation. … This is the house that she built.”

“She opened another door,” said former player Yolanda Shavies, remembering how Johnson took Tech’s players to travel across the state for competitive tournaments. “Because she played, she knew this world.”

Johnson recruited boys as practice players. “You know the story, ‘There’s no crying in baseball’? It was like, ‘There’s no crying in basketball!’ You just get out there, suck it up and play.”

It’s no accident that two of those boys were future girls basketball head coaches, Leroy Hurt and his predecessor, Pico Wilburn. In Oakland Tech’s modern era, Hurt and Wilburn combined have led the Bulldogs to five state championships since 2004. As teenagers, both men looked up to Johnson. “I talked to her more than I talked to my own coach,” Wilburn said matter-of-factly. “She brings something out of basketball that no one else does.”

Johnson has been a coach to many beyond the kids at Oakland Tech. After she left the program, she continued coaching girls basketball across the East Bay while juggling a job in management at FedEx. She formed her own AAU team between 2004-2007, which she named after her greatest strength, XTremeD. But it was Tech where she left the biggest mark.

At the hall of fame ceremony in February, Hurt beamed to the crowd, as Johnson stood at center court. “Listen,” he said. “Without Coach Johnson, there would be no Leroy Hurt. Without Coach Johnson, there would be no Coach Pico.”

Hurt pointed to Johnson. “Coach Johnson, this is her house,” he said. The crowd was silent, focused on Johnson. He continued: “I want everybody to know that she laid the foundation. … This is the house that she built.” The crowd roared in agreement.

On a sunny day this past winter, Johnson set out for a walk wearing a purple and black Valkyries sweatshirt. She was in one of her favorite places: the Emeryville Marina. The jutting walkway, set alongside craggy rocks and the sparkling waters of the bay, are also where Johnson’s father took her fishing as a young kid. And it’s where she and her mother Ruth loved to go together. “She never used a wheelchair in her life,” Johnson said. “Never used a walker in her life. Never used a cane in her life. She always walked.”

When Anna, right, was inducted into the Women’s Basketball Hall of Fame, her mother, Ruth, left, was lovingly brusque: “It’s about damn time.” Credit: Courtesy Anna Johnson

When Anna, right, was inducted into the Women’s Basketball Hall of Fame, her mother, Ruth, left, was lovingly brusque: “It’s about damn time.” Credit: Courtesy Anna Johnson

For the last six years, Johnson set aside nearly everything to take care of her mother, who was still walking over a mile at the marina well into her 90s. In fact, Johnson retired early from her job at FedEx in 2020 to protect her mom from COVID-19. After that, they spent nearly all their time together. Mother and daughter delighted one another with their dry sense of humor, ate breakfast every day, went on long walks by the bay, reflecting on Johnson’s remarkable time as a basketball player. Ruth knew better than anyone what her daughter had given the sport. When Johnson was inducted into the Women’s Basketball Hall of Fame alongside about 100 other former WBL players, Ruth’s response was lovingly brusque: “It’s about damn time.” And now, near the end of her life, mom had one more vision for her daughter’s career: that one day, she would tell her story. “Just make sure you get it right,” Ruth told her.

In November of 2024, Ruth Johnson passed away at the age of 98. Johnson goes to the marina to feel her mother’s spirit. “It gives me peace and it relaxes me,” she said. And it’s here in Emeryville that Johnson also feels a sense of purpose, inspired by her mom. Now more than ever is the time to tell her own story. “It is kind of like therapy to be able to talk about it at this point,” Johnson reflected, watching the sun flickering across the water. Perhaps that’s why she first spoke up when talking to the Valkyries sales rep.

These days, Johnson is in close touch with former Pioneers teammates like McKinney and Hicks. They call each other up to fantasize about the potential of a reunion. “You better be ready,” McKinney recently told Johnson. And Johnson, who plans to attend every Valkyries home game this season, certainly will be ready. All the Pioneers want, she said, is a simple thank you. Done the right way, of course: by honoring the entire team, together, at the same time.

But Johnson is elated to be a ride-or-die Valkyries supporter. “I was a player, and now I’m a fan,” she said, pushing the pace as she rounded the corner toward her mother’s favorite bench at the edge of the marina. From here she’d look out at San Francisco, where the Johnson family first lived after migrating from the South in the 1950s. Standing there, by the water, Johnson smiled. “It’s nice to know that women’s basketball was here before,” she said. “And now that it’s back, let’s keep it here. Let’s not falter again. … We wanna move forward, we wanna keep on pushing.”

Maya Goldberg-Safir splits her time between Chicago and Oakland, where she was born and raised. She is the creator of Rough Notes, a newsletter chronicling women’s basketball from the court, the road, and the heart.

“*” indicates required fields