Colorado lawmakers are facing their second budget cycle in a row in which they’re forecast to have about $1 billion less than they need to continue current levels of state programs and services.

And the legislature was recently warned that they face a third billion-dollar shortfall in 2027 if nothing changes.

The primary culprit? Medicaid, the health insurance program that covers roughly 1.2 million low-income Coloradans. The state’s price tag of administering the program has risen dramatically in recent years, far outpacing the voter-imposed cap on government growth and spending.

The Colorado Sun dug into the data to learn just how much of a burden Medicaid has become on the state budget and why, as well as what is being proposed to address the issue.

(To understand who Medicaid covers and how they qualify, see this explainer from earlier in the year.)

TABOR

In order to understand why the rising cost of providing Medicaid services in Colorado is such a problem, you first have to understand the Taxpayer’s Bill of Rights.

TABOR is the constitutional amendment approved by voters in 1992 that requires voter approval for all tax increases and caps government growth and spending each year based on increases in inflation and population.

Because of TABOR, the legislature can’t simply vote to raise taxes to account for the increased cost of providing Medicaid. And it can’t even use all of the money the state collects from existing taxes to cover the rising cost of Medicaid. Anything collected in excess of the TABOR cap must be refunded to taxpayers.

That means when the annual increase in the cost of providing Medicaid in Colorado exceeds the increase in the TABOR cap, the legislature really only has two options: pare back Medicaid offerings or cut other state programs and services.

How much the cost of administering Medicaid has increased

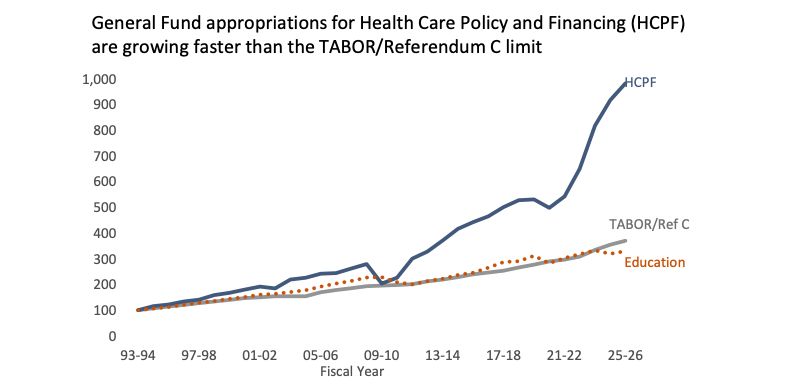

Now that you’ve got an understanding of TABOR, you can compare it with how Medicaid costs have increased in Colorado.

Medicaid is jointly funded by the state and federal governments. Costs are generally split 50/50, but in some cases the federal government pays a larger share.

With some exceptions, Colorado pays its share out of the state’s general fund, the unrestricted pot of money that can be used for any number of other government programs. Medicaid costs account for about 36% of the total state budget, which includes all the federal funding the state receives. It’s about 31% of just the general fund budget, and that is where it runs into TABOR.

Since the 2018-19 fiscal year, the TABOR cap has increased by 39%.

The cost of providing Medicaid over that period has increased much faster — about 86%, or $2.6 billion.

Annual increases in Medicaid costs have generally exceeded increases in the TABOR cap since the cap was implemented in the 1993-94 fiscal year. The increase in Medicaid spending relative to the TABOR cap increase started to balloon in the 2011-12 fiscal year and became even more pronounced starting in fiscal year 2021-22. That’s when the governor’s office says the gap started to become unmanageable.

So the problem has been compounding for more than a decade.

This chart from nonpartisan staff for the legislature’s Joint Budget Committee provides a better picture of how the percentage increase in Medicaid spending in Colorado compares with growth in the TABOR cap:

“Since FY 2018-19, General Fund appropriations for Medicaid have grown far faster than inflation. Appropriations to most departments have roughly kept pace with inflation,” JBC staff told the committee in a recent report.

Here are some more detailed figures showing the increased cost of Medicaid in Colorado:

The Medicaid cost of covering specialty drugs, like gene therapy medications, has increased 82% since the state’s 2018-19 fiscal year. High-cost drugs represent just 1.5% of the drugs dispensed to Medicaid patients in Colorado, but they represent about 50% of the state’s Medicaid prescription drug spending.

The cost of Medicaid coverage for behavioral health services has increased by 115% since 2018-19.

The cost of providing Medicaid coverage for pediatric behavioral therapies for kids with autism and other developmental disorders increased by 306% between the 2018-19 and 2023-24 fiscal years.

Long-term care services for Medicaid recipients increased in cost 44% to $4.1 billion from $2.9 billion between the 2020-21 and 2023-24 fiscal years.

“In the last 40 years, no commercial or Medicaid health plan has consistently controlled its trends at or below inflation,” Kim Bimestefer, who leads the Colorado Department of Health Care Policy and Financing, which administers Medicaid, said in a presentation to providers.

Making matters worse: Medicaid spending has been surpassing expectations. Last fiscal year, the state spent $69 million more on Medicaid than it expected, eating into the budget’s reserves.

Why Medicaid costs have increased so much

Medicaid costs have grown for a number of reasons, some outside the state’s control and some the result of decisions by lawmakers.

First, the cost of medical care is increasing generally. The accounting firm PwC estimates that inflation for private health insurance companies will be roughly 8% next year, in line with higher inflation trends following the COVID pandemic.

Second, the amount of care people use — what health care finance analysts call “utilization” — is increasing as well. Bimestefer said the trend took off after the pandemic as people went back to the doctor for care they had postponed during the shutdown.

Third, while the number of people covered by Medicaid has plummeted since the end of the pandemic, some of those who remain covered have a big impact on the budget. This is especially true of people who are disabled and people ages 65 and older who are in long-term care. (Medicare does not pay for nursing home care, but Medicaid does for those unable to afford it.)

A bed inside the St. Anthony Summit Medical Hospital, March 15, 2024, in Frisco. (Hugh Carey, The Colorado Sun)

A bed inside the St. Anthony Summit Medical Hospital, March 15, 2024, in Frisco. (Hugh Carey, The Colorado Sun)

At one point during last year’s budget-writing process, legislative budget staff projected that the number of people 65 and older covered by Medicaid during the current fiscal year would increase by 4,000 — up about 5%. That increase was expected to add $121 million to the budget. A 6%, or 6,000-person, increase in the number of people with disabilities was expected to add $305 million.

“We had this precipitous drop in adults and children,” Eric Kurtz, a chief legislative budget and policy analyst with the legislature’s Joint Budget Committee explained during one committee hearing. “But it just didn’t decrease our expenses enough to offset the increase for the elderly and people with disabilities.”

Overall, people who are disabled and people who are older made up 9% of the state’s Medicaid enrollment in the 2023-24 fiscal year but accounted for 50% of the program’s overall spending — and 70% of its general fund spending.

A similar dynamic is at work with high-cost specialty drugs that have come to market in recent years, including treatments for cancer, HIV, cystic fibrosis, hepatitis and autoimmune conditions. Specialty drugs account for about 2% of Colorado Medicaid’s overall prescriptions but are 50% of the program’s pharmaceutical spending, Tom Leahey, the program’s pharmacy director, said on a webinar earlier this year.

How lawmakers have added to Medicaid’s budget

Decisions at the state Capitol have also had an impact on Medicaid’s expanding budget, though. In recent years, lawmakers have voted to increase the payment rates for Medicaid providers and to expand services that are covered.

Some of those payment increases are what Bimestefer referred to as “systemic investments” in areas where support had long been lacking. She mentioned behavioral and mental health care, in particular.

Other increases sought to financially stabilize Medicaid providers given that Medicaid often doesn’t pay the full amount of what it costs to provide a service. As recently as 2019, Medicaid in Colorado paid only 63 cents on the dollar for care, according to a state report. That rate is now up to 79 cents on the dollar.

Coverage expansions have also added to Medicaid spending.

In the last five years, dozens of bills have increased Medicaid benefits. Those bills typically had price tags in the hundreds of thousands to tens of millions of dollars. But the annual amount spent for them grows larger over time as inflation, utilization and enrollment increase.

Here are some of the most notable changes:

A bill in 2021 allowed people who gave birth while covered by Medicaid to remain enrolled for the following 12 months. It was expected to add about $19 million to the Medicaid budget, including $8 million in general fund spending. The bill was sponsored by Democrats.

A bill in 2022 extended Medicaid coverage to children and pregnant women who would be eligible for Medicaid except for their immigration status. The program took effect in 2025. It is expected to cost about $96 million in the current fiscal year — $53 million to cover the kids and $43 million for the pregnant women. But the federal government will pick up 65% of the costs for the latter group. Some of the cost may also offset money that would have otherwise been spent out of a nationwide program called Emergency Medicaid. The bill was sponsored by Democrats and then-Sen. Kevin Priola, who was a Republican at the time but later switched his affiliation to become a Democrat.

A bill in 2023 directed Colorado’s Medicaid program to seek federal approval to pay for services provided by community health workers. It was expected to increase spending by $12 million, including $3.7 million out of the general fund, by the current fiscal year. The bill had bipartisan sponsorship.

Another bill in 2023 that removed the requirement for Medicaid recipients to pay a copay for prescriptions and outpatient services. It was expected to cost about $7.3 million per year, including $1.4 million out of the general fund. The bill had bipartisan sponsorship.

A bill in 2024 that expanded treatment programs for substance use disorders. It was expected to cost $7.3 million in the current fiscal year, including $2.6 million of general fund money. It had bipartisan sponsorship.

Another bill in 2024 that expanded programs for youth currently or at risk of being placed in treatment programs outside of their homes. It was expected to cost $34 million in the current fiscal year, with $23.5 million of that coming from the general fund. It had bipartisan sponsorship.

The voting board in the Colorado House of Representatives at the state Capitol on May 3, 2025. (Jesse Paul, The Colorado Sun)

The voting board in the Colorado House of Representatives at the state Capitol on May 3, 2025. (Jesse Paul, The Colorado Sun)

There’s also one other significant way that state lawmakers have added to the Medicaid budget, but it doesn’t have the impact you might expect.

The Affordable Care Act, also known as Obamacare, allowed states to expand Medicaid eligibility to people earning up to 138% of the federal poverty level. Colorado opted in during the 2014-15 fiscal year. While that had a big effect on Colorado’s uninsured rate — dropping to 6.5% from 15.8% — it “came at a cost,” Bimestefer said.

At first, the cost of the expansion was fully covered by the federal government. Colorado is now on the hook for 10% of the cost. About 370,000 people are covered by the expansion, and total spending on that group now accounts for about 23% of the program’s overall budget.

But none of that money comes from the state’s general fund. Colorado pays its share of the costs using the hospital provider fee, a complicated mechanism used by many states to draw down extra Medicaid dollars to benefit hospitals or fund coverage expansions. In Colorado, the system does both, providing about $500 million a year to hospitals while also paying for Medicaid expansion.

The One Big Beautiful Bill Act

The One Big Beautiful Bill Act, the federal tax and spending bill passed by Republicans in Congress this year and signed by President Donald Trump, will also have an effect on Medicaid spending in Colorado.

Most notably, it will impose work requirements and more frequent eligibility checks on those covered by the Medicaid expansion starting in 2027. Analysis by the Urban Institute has estimated this provision could cause about 100,000 people in Colorado to lose Medicaid coverage.

This would reduce overall Medicaid spending in Colorado. But, because the federal government pays 90% of the cost of the expansion, this provision would mostly save federal dollars. It would not save money in the state general fund.

The Department of Health Care Policy and Financing believes it will cost the state $57 million in administrative costs the first year the work requirements are imposed to process and monitor eligibility.

Another provision of the bill would gradually limit the amount of money Colorado could collect through the hospital provider fee system, shrinking the dollars available for the state to pay its share of the Medicaid expansion. The Colorado Hospital Association estimates that the state will see a $10.4 billion reduction in provider fee money over the next five years as a result of the provision.

The bill also makes a number of other significant changes. It shrinks the number of legal immigrants who are eligible for Medicaid, and it reduces how much the federal government pays for its share of Emergency Medicaid, which reimburses hospitals for emergency care they are legally required to provide to people who would be eligible for Medicaid but for their immigration status.

The bill cuts funding for specially targeted payment rates known as state-directed payments, and the bill also reduces the window for retroactive Medicaid coverage.

The health care nonprofit KFF estimates that, all told, Colorado will see about $12 billion less in federal funding between now and 2034. Bimestefer said the state is working to absorb the bill’s impacts without cutting anyone off from Medicaid.

“To be clear, we are going to do everything we can to keep eligible Coloradans enrolled,” she said.

Why the governor is taking it on — and what he’s proposing

If the state were to keep Medicaid services the same next fiscal year, which begins July 1, the cost would exceed the annual increase in the TABOR cap by about $12 million.

To account for those costs, the legislature would be forced to make cuts in other areas to produce a balanced budget, a requirement under state law. And there wouldn’t be any money left to cover the increased cost of providing other government programs and services across billions of dollars in state spending.

The legislature’s Joint Budget Committee is just starting out its budget-writing process and hasn’t made any decisions about how to handle the increasing costs of providing Medicaid. But Gov. Jared Polis, entering his last year leading the state and signaling a readiness to tap his remaining political capital, has already submitted his 2026-27 budget proposal to the JBC, and it includes Medicaid cuts.

Polis’ plan calls for increasing Medicaid spending next fiscal year by nearly $300 million. That’s less than half of the $631 million increase in projected costs if the state kept its Medicaid offerings the same.

Gov. Jared Polis, flanked by Lt. Gov. Dianne Primavera and Mark Ferrandino, who leads the Governor’s Office of State Planning and Budgeting, presents his 2026-27 budget proposal during a news conference on Friday, Oct. 31, 2025, at the governor’s mansion in downtown Denver. (Jesse Paul, The Colorado Sun)

Gov. Jared Polis, flanked by Lt. Gov. Dianne Primavera and Mark Ferrandino, who leads the Governor’s Office of State Planning and Budgeting, presents his 2026-27 budget proposal during a news conference on Friday, Oct. 31, 2025, at the governor’s mansion in downtown Denver. (Jesse Paul, The Colorado Sun)

The program could hold down expenses by capping some reimbursement rates for providers and limiting how much recipients can receive in dental benefits, the governor’s office said. Other Medicaid cost-saving proposals from the governor include limiting home caregiver hours and reducing pay for health workers who supervise people with autism.

In the long term, Polis wants the legislature to tie increases in Medicaid spending to the TABOR formula. That way Medicaid spending couldn’t outpace the annual TABOR cap growth.

The governor’s office and Bimestefer believe the state can accomplish that with efforts to get people off Medicaid through socioeconomic initiatives, like increasing educational offerings and job training.

Medicaid advocates and state lawmakers are chafing at the governor’s proposal.

“Do not balance the budget on the backs of disabled children and their families,” Rebecca Urbano Powell, executive director of Seven Dimensions Behavioral Health and president of the Colorado Association for Behavior Analysis, said at a recent rally at the state Capitol.

Rebecca Urbano Powell, executive director of Seven Dimensions Behavioral Health and president of the Colorado Association for Behavior Analysis, speaks at a rally criticizing Gov. Jared Polis’ proposed Medicaid cuts at the Colorado Capitol in Denver on Tuesday, Nov. 18, 2025. (Jesse Paul, The Colorado Sun)

Rebecca Urbano Powell, executive director of Seven Dimensions Behavioral Health and president of the Colorado Association for Behavior Analysis, speaks at a rally criticizing Gov. Jared Polis’ proposed Medicaid cuts at the Colorado Capitol in Denver on Tuesday, Nov. 18, 2025. (Jesse Paul, The Colorado Sun)

Some Democrats in the legislature want to raise more tax revenue or tap dollars in excess of the TABOR cap to help address the increasing cost of Medicaid. Both proposals would require voter approval, and voters have historically been unwilling to increase their taxes and forgo the refunds they are entitled to when the TABOR cap is exceeded.

Republicans in the legislature, meanwhile, are pushing for cuts to state agencies. They want those dollars redirected toward Medicaid spending. But cuts to other state programs and services, which are already being requested by the governor’s office, likely can’t make up for all of the increased Medicaid spending, especially since it’s only expected to grow in future years.

Type of Story: News

Based on facts, either observed and verified directly by the reporter, or reported and verified from knowledgeable sources.