Like many parents, Andrew David keeps a close eye on what programs his 6-year-old son is consuming, often watching shows on YouTube, Netflix, or Disney+ with him or sitting nearby and listening in. But when he looks over and sees the PBS Kids logo, he feels he can stand down.

“It is one thing that we don’t have to worry about,” said David, 42, a history lecturer at Boston University who lives in Waltham. “It’s going to be fine, and more often than not, he’s going to like it.”

David is among the generations of adults who themselves were weaned on “Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood,” “Reading Rainbow,” and other PBS classics at a time when public broadcasting’s main competition was largely Bugs Bunny and other famous cartoon characters. He’s not alone in his confidence of the public broadcaster: A YouGov survey earlier this year found that 88 percent of parents agreed that PBS is a trusted source for kids’ shows and games.

Fred Rogers and David Newell, as Speedy Delivery’s Mr. McFeely, stood on the front porch set while filming an episode of “Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood.”Lynn Johnson

Fred Rogers and David Newell, as Speedy Delivery’s Mr. McFeely, stood on the front porch set while filming an episode of “Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood.”Lynn Johnson

But the Trump administration’s war on public broadcasting for alleged political bias has come down hard on children’s programming.

At the same time parents and families are faced with an ever-expanding menu of commercial programming, amateur video, and AI slop, PBS is under some of the greatest pressures of its half-century existence. After PBS Kids lost nearly $30 million for children’s programming due to federal funding cuts, public media executives say they’re straining to cover the costs of developing and distributing children’s programming that can break through the noise.

“I worry that PBS will have fewer opportunities to hold the attention of kids and families,” said Shelley Pasnik, senior vice president of external affairs at the nonprofit Education Development Center. “Attention fragmentation is something that is not unique to this moment, but it will be exacerbated by the loss of funding.”

PBS Kids has cut 30 percent of its staff this year, while GBH has laid off an undisclosed number of employees working on children’s programming. Other local stations across the country have also let go of staff, and some have announced plans to close entirely.

Additionally, PBS Kids might have to cut back on some gaming and accessibility features, said Sara DeWitt, senior vice president and general manager of PBS Kids. She added that one of the first big features that will likely go will be the ability for viewers to download PBS Kids games and play them offline, due to the costs associated with maintaining that feature.

While PBS is still producing new shows — it launched the Al Roker-created “Weather Hunters” in September and will soon air a new series, “Phoebe and Jay” — the organization cautioned that it is soon facing a programming cliff.

“We don’t have a much longer pipeline, because the things that were in development are having to stop,” DeWitt said. “We usually launch one to two new shows a year, and right now, we’re looking at about half that for the future.”

Henry David, 6, put his feet up while watching one of his favorite PBS Kids shows, “Weather Hunters,” on Dec. 4.Ken McGagh for The Boston Globe

Henry David, 6, put his feet up while watching one of his favorite PBS Kids shows, “Weather Hunters,” on Dec. 4.Ken McGagh for The Boston Globe

That stands in stark contrast to the bounty of commercial programming on streaming services and broadcast television, not to mention the increase of AI-generated content on social media.

Meryl Alper, an associate professor at Northeastern University who studies children’s media, has worked with both public and private organizations that create kids’ content. She said that while both entities can create educational content, public media has been unique because research- and evidence-backed educational programming is the focus from the start, not profit. That’s not the same with commercial programs.

“If it doesn’t sell toys, it’s not going to get another season,” she said.

For decades, public children’s programming has primarily been supported by donations, sponsorship, and taxpayer funding — mainly from the Corporation for Public Broadcasting and the Department of Education’s Ready to Learn grants. And, in an age of ad-ridden streaming sites and paywalled streaming services, PBS has remained free to watch.

The Ready to Learn awards provided funding for children’s programming that focused on delivering educational content to preschool and early elementary students, particularly those from low-income families. Among the PBS shows that were funded by the grants was “Skillsville,” an animated series where three friends learn life skills by trying out careers in a video game, which was a favorite of Andrew David’s son.

But in May, the Department of Education terminated the grants. That meant that “Skillsville,” which had premiered just two months before, had to halt production and cut staff, according to reports at the time. And President Trump rescinded funding for CPB in July.

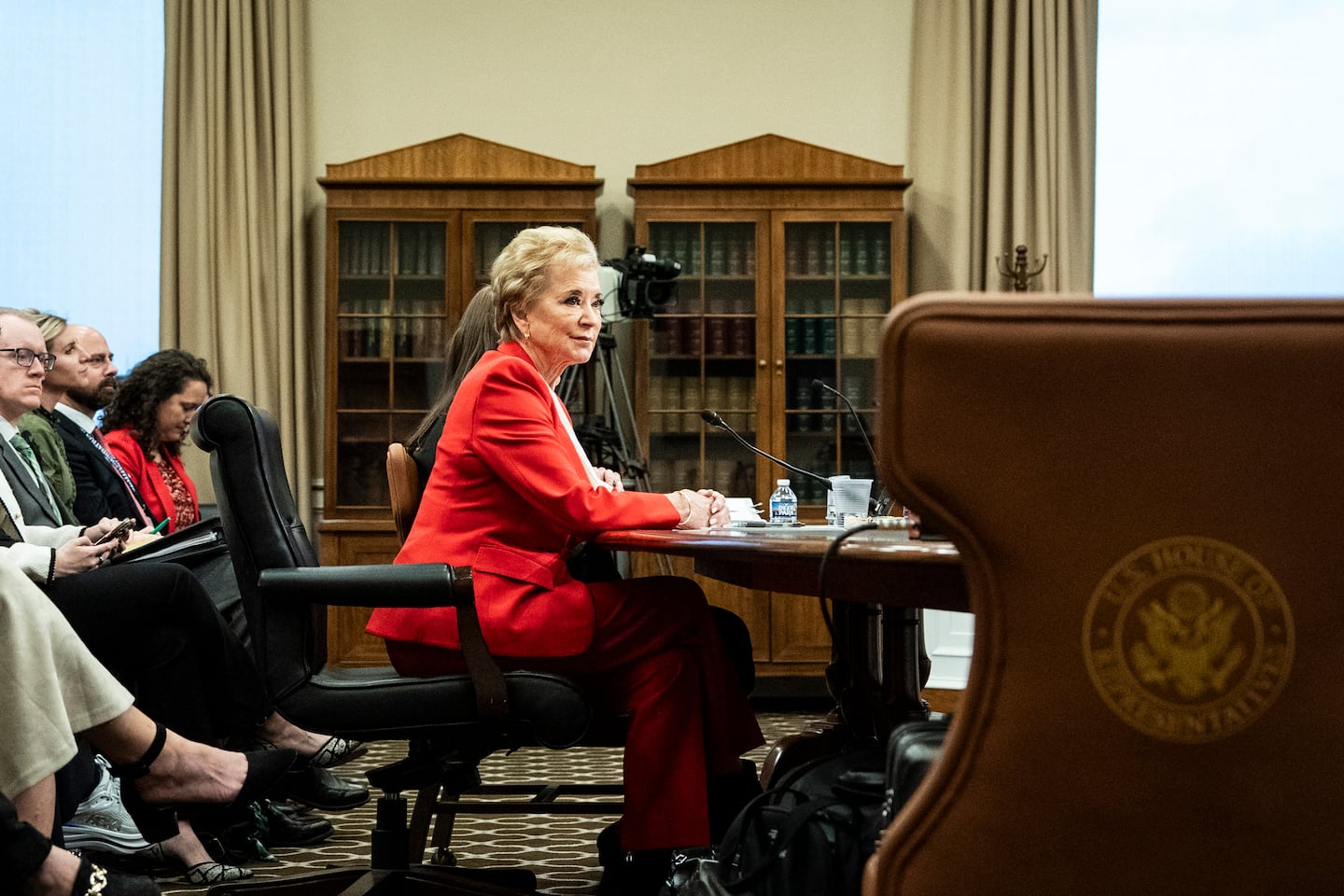

Education Secretary Linda McMahon testified at a House Appropriations Committee hearing on Capitol Hill in Washington on May 21.HAIYUN JIANG/NYT

Education Secretary Linda McMahon testified at a House Appropriations Committee hearing on Capitol Hill in Washington on May 21.HAIYUN JIANG/NYT

“Watching all these shows, seeing the Corporation for Public Broadcasting, you’re watching revenue streams that made these things happen — it’s like watching tombstones on the screen,“ David said.

Only a small team is left at CPB before it shuts down next month. And with Trump also gutting the Department of Education, the role in overseeing Ready to Learn has been transferred to the Department of Labor.

When asked about the future of Ready to Learn, a Department of Education spokesperson referred to a statement the agency previously issued when the government canceled the grants that asserted the program was funding “racial justice educational programming” and was “not aligned with Administration priorities.”

Researchers who have worked with PBS, GBH, and other public media organizations said PBS Kids programming is distinguished by its research throughout development of its programs. That can often take anywhere from two to five years, said Seeta Pai, vice president of children’s media and education at GBH.

It’s an elaborate process: organizing researchers and staff to create a curriculum, creating characters and ensuring their personalities and plot lines are tied to the learning plan, finding a cast, reviewing scripts with both educators and the creative team, developing the program alongside games and educational resources, and testing content with kids along the way.

“We program with intent and with education and affirmation of children in mind, in contrast to a lot of what else is out there and what kids can access, and now with AI slop just further increasing the vast wasteland,” Pai said.

Ready to Learn-funded studies have found that programs such as GBH’s “Molly of Denali” helped strengthen literacy skills and PBS Kids’ “The Cat in the Hat Knows a Lot About That!” taught key science and engineering skills.

“The Ready to Learn program was the single largest investment in research involving kids in media,” said Pasnik, who led the research arm of Ready to Learn. “Nothing matched it.”

Max Bridges, parent of a 2-year-old and a 6-year-old in Somerville, referred to PBS Kids as “an oasis in a desert” of children’s content.

While he values programs such as “Bluey,” which streams on Disney+ but was co-commissioned by British Australian public broadcasters, he is particularly sensitive to how streaming services and social media sites can hold people’s attention, having earned a master’s degree in human-computer interaction.

The 39-year-old Bridges described how, at his in-laws’ house for Thanksgiving, he looked across the room and saw his older son watching a YouTube video that showed other kids playing with toys from big brands.

“There isn’t any care taken to the viewer and their nurturing and their emotional growth or social growth or intellectual growth,” he said. “That does not happen with the PBS stuff.”

Signs supporting NPR and PBS sat outside NPR’s headquarters in Washington, on March 26. ERIC LEE/NYT

Signs supporting NPR and PBS sat outside NPR’s headquarters in Washington, on March 26. ERIC LEE/NYT

The cuts are limiting other research at PBS Kids. DeWitt cited an NSF-funded study between PBS Kids and researchers at Harvard University and the University of California, Irvine that examines how effective AI-powered conversational episodes of children’s programs are on learning.

She said it’s one way that PBS is trying to understand the potential benefits of emerging technology. But funding cuts will limit the public launch of those episodes.

“I’m very concerned that there are very few entities who are in a position to be able to do that kind of work, to look at what’s happening right now with AI,” she said.

Make no mistake: PBS isn’t going away. While it will reduce some of its features and shows, executives said that anyone who wants to access PBS programming will be able to do so, even in rural parts of the country where internet access is limited and some PBS stations are closing.

“All kids can still access us,” DeWitt said. “I think the bigger thing for us is making sure that parents know we’re still here.”

Aidan Ryan can be reached at aidan.ryan@globe.com. Follow him @aidanfitzryan.