A wolf from the Wapiti Lake Pack in Yellowstone National Park stares through the trees in fall 2025. For decades, scientists have debated the concept of the trophic cascade. New research suggests it might not be that simple. Credit: Ben Bluhm

A wolf from the Wapiti Lake Pack in Yellowstone National Park stares through the trees in fall 2025. For decades, scientists have debated the concept of the trophic cascade. New research suggests it might not be that simple. Credit: Ben Bluhm

Around Crystal Creek, where the road bridges the Lamar River at the fringe of Yellowstone National Park’s Lamar Valley, a grove of aspens has new life. In 1997, the first year scientists began systematically measuring the park’s aspen population, the stand consisted of towering, century-old trees with no fresh growth in the understory.

Today, the scene is dramatically different. A thicket of young aspens now blankets the ground. Many of the saplings are already taller than the researchers who study them. The grove is not only denser, it expanded its footprint.

Crystal Creek has become synonymous with the ecological benefits of wolf restoration. It’s home to one of the pens where wolves were kept during their 1995 reintroduction, and it’s also a hotspot where aspen growth has surged over the past three decades.

Quaking aspens grow in colonies, sending up genetically identical shoots from a shared root system. In much of the 1900s, massive elk herds devoured virtually every new aspen shoot that broke through the soil, stifling the growth of new trees.

But shortly after the 1995 wolf reintroduction, the elk population fell and some aspen sprouts slipped past the hungry herbivores. While a flood of news articles, Facebook posts and YouTube videos have attributed the change to wolves, scientific evidence for this conclusion is limited. And some scientists believe that aspen regrowth in the park has been exaggerated.

An aspen stand in Yellowstone with few new sprouts growing. Credit: Yellowstone Forever

An aspen stand in Yellowstone with few new sprouts growing. Credit: Yellowstone Forever

BEFORE WOLF RESTORATION

The idea that canines protect Yellowstone’s aspens from herbivores dates back at least a century. In the late 1800s and early 1900s, rangers in the park shot hundreds of wolves, bears, cougars and coyotes in a bid to boost deer and elk numbers. In 1926, the same year park rangers wiped out Yellowstone’s last wolf pack, biologist Edward Warren was already warning that the carnivore purge was harming the park’s aspen groves.

“There has doubtless been a great increase in the number of beaver in the Yellowstone Park of late years,” he wrote in his 222-page report. “When over two hundred coyotes are killed in a single season, as in 1922, the animals which formed part of their food are bound to profit by it and to increase in numbers. The result has been what is probably an unnatural expansion of the beaver population.”

Warren went on to describe what zoologist Robert Paine would 54 years later call the “trophic cascade.” The expanded beaver population had chomped down nearly all of the large aspen trees near the streams and ponds of Tower-Roosevelt. While thickets of young sprouts remained, most trees near beaver dams with a trunk greater than two inches had become food or building material.

Aspen stand with strong regrowth (left) and aspen stand with little regrowth (right). Credit: Dan MacNulty.

Aspen stand with strong regrowth (left) and aspen stand with little regrowth (right). Credit: Dan MacNulty.

By 1955, both beavers and aspens had disappeared from the ponds and creeks of Tower-Roosevelt. Beavers had chewed down the old trees, while the soaring elk population had consumed the young ones, suggested William Barmore, a park biologist who studied the park’s elk herds. Aspens continued to survive beyond the beavers’ reach, but these groves, which Barmore described in a 1965 research report, looked very different from the ones Warren photographed.

“In most stands the only aspen age classes present were decadent, overmature trees and root sprouts from one to a few years old that were browsed off to a height of one or two feet each winter,” Barmore wrote. He noted that hungry elk chomped down on aspen shoots each winter when grass was scarce, preventing any sprouts from becoming mature trees.

An individual aspen seldom lives more than 200 years. Without successful regeneration, entire stands disappeared as the old trees died.

Barmore believed that elk were responsible. “Sometime after 1880 the relative number of elk utilizing park ranges, particularly during the winter, began to increase,” he wrote, listing hunting and development north of the park, as well as “predator destruction,” as possible causes. “Whether the increased use of park winter ranges resulted from an actual drastic increase in the herd or from a bottling up of an abnormally large number of animals on previously marginal winter range is not known,” he added.

Decades of heavy elk browsing left a lasting impact. Studies have found that between 1921 and 1999, new aspen trees grew only on scree slopes and among fallen trees that physically blocked elk access.

Yellowstone’s Druid wolf pack chases a bull elk in the park, December 2007. Credit: Doug Smith / NPS

Yellowstone’s Druid wolf pack chases a bull elk in the park, December 2007. Credit: Doug Smith / NPS

A TROPHIC CASCADE

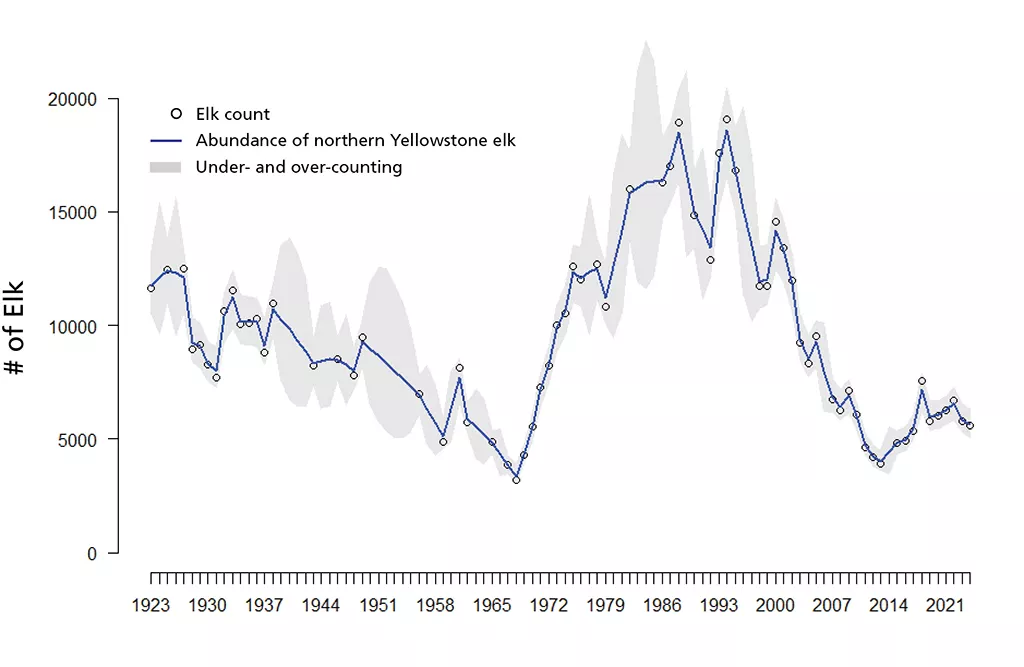

At the dawn of the 21st century, the situation began to change. The winter elk population in northern Yellowstone fell from a record high of 17,000 in 1995 to less than 2,000 by 2012. Multiple studies conducted in the early 2000s showed that some aspen sprouts were escaping elk browsing and growing tall.

A study published in July 2025 summarized more than two decades of data, finding that the number of young trees taller than six feet increased more than ten-fold between 1998 and 2021. While new aspen trees were virtually absent from northern Yellowstone in 1998, the study found, 43 percent of stands contained them by 2021.

The surge in new growth seemed to parallel the 1995 wolf reintroduction, and media coverage highlighted the connection. “Since wolves’ return, Yellowstone’s aspens are recovering,” read one Washington Post headline in August 2025. “Aspen trees are returning in Yellowstone, thanks to wolves,” read a July 2025 headline from the aptly-named Aspen Public Radio in Aspen, Colorado.

Daniel MacNulty, an ecologist at Utah State University, took issue with these conclusions. In a recent critique, he highlighted a small number of exceptional stands that drove the large increase in trees described in the study, while most aspens showed little change over the same period.

Luke Painter, the Oregon State University ecologist behind the study, agreed that the headlines simplified the data. “There are significant changes, and there are beginnings of recovery, but it’s patchy and it isn’t happening everywhere,” Painter told Mountain Journal. “But a trophic cascade does not have to be everywhere to be significant.”

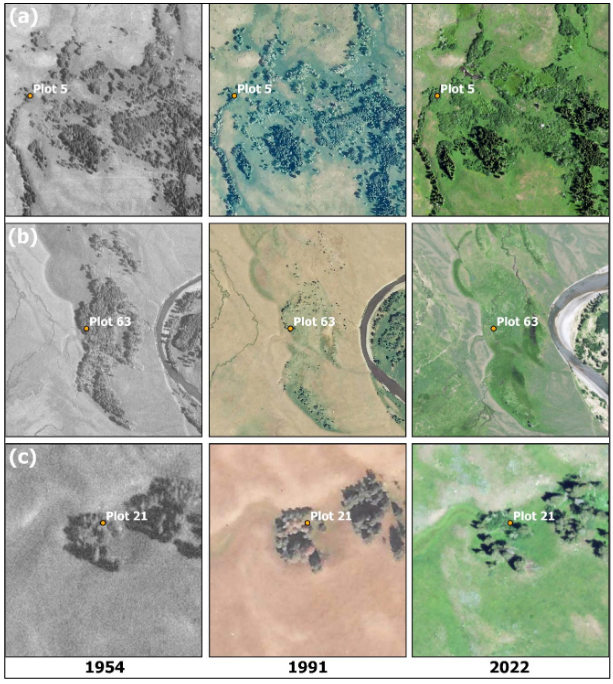

In a recent master’s thesis from MacNulty’s Utah State lab, scientists argue that the surge in young trees might be less impactful than previously stated. They used aerial photos to measure the physical area covered by 73 aspen stands on the Northern Range in 1954, 1991 and 2020. The results, which have not been previously reported by any media outlet, show that most aspen stands have continued shrinking since wolf reintroduction.

“Maybe there’s some good regeneration in the heart of the stand. But the rate of contraction actually increased after wolves were introduced.”

Nicholas Bergeron, researcher, utah state university

Between 1954 and 1991, when elk populations in Yellowstone reached record highs, the average size of the 73 stands studied dropped 54 percent. Aspen groves then shrank another 59 percent between 1991 and 2020, despite wolf reintroduction in 1995. Only seven of the 73 stands grew larger during after 1991, and Crystal Creek was one of them.

It remains to be seen whether enough young aspens are surviving to reverse the decades-long decline. “Maybe there’s some good regeneration in the heart of the stand,” said Nicholas Bergeron, author of the thesis. “But the rate of contraction actually increased after wolves were introduced.”

Painter believes aspens appear to be declining because many aspens on the Northern Range are near the end of their lives. “The older trees have been dying off at an accelerated rate since the 1990s,” Painter said in response to the thesis. “Of course it looks like the stands are shrinking. Some of them have lost all their large trees.”

Even where aspens are making a comeback, scientists debate the role that wolves have played.

A wolf peers through a stand of leafless aspen trees in Grand Teton National Park, spring 2024. Credit: Ben Bluhm Credit: Ben Bluhm

A wolf peers through a stand of leafless aspen trees in Grand Teton National Park, spring 2024. Credit: Ben Bluhm Credit: Ben Bluhm

TYING IT TO WOLVES

The grasslands and sagebrush steppe of Yellowstone’s Northern Range support the park’s largest elk herd. Each winter, when snow piles up in the high county, thousands of elk descend into the valleys of northern Yellowstone and adjacent lands. The herd has shrunk dramatically over the past three decades: from 17,000 in 1995 to 6,673 in 2022, according to some of the most recent data from the Park Service

“Elk have declined a lot since wolves were reintroduced, but it’s not clear that that’s due to wolves,” said Chris Wilmers, an ecologist at the University of California, Santa Cruz and the author of another recent study that assessed the impacts of large carnivore recovery across North America. “Other predators have been recovering, there’s been a lot of human hunting of elk, there’s a growing bison population that’s competing substantially with elk, and outside the park ranchers are increasingly tolerant of elk feeding in their irrigated pastures so they have less of a need to migrate into the park in the first place.”

“Most ecologists suspect that wolves and other predators have something to do with the decline of elk,” Wilmers continued. “But how much can be attributed to wolves, how much can be attributed to predators in general, how much is attributed to those other causes hasn’t been worked out yet.”

A figure from Bergeron’s thesis showing a stand with increasing aspen cover (a), decreasing aspen cover (b), and unchanging aspen cover (c). Credit: Nick Bergeron

A figure from Bergeron’s thesis showing a stand with increasing aspen cover (a), decreasing aspen cover (b), and unchanging aspen cover (c). Credit: Nick Bergeron

Cougars, hunted aggressively within the park in the early 1900s, have increased in numbers since the 1980s. As well, the number of grizzly bears in Greater Yellowstone spiked from 136 in 1975 to about 1,030 in 2024 due to federal protections. Between 1998 and 2004, cougars probably killed more Northern Range elk than wolves, and grizzly bears are the main predator of elk calves, potentially contributing to their lower numbers.

“Elk population dynamics are extraordinarily complex and you really can’t pin elk numbers to any one thing,” said wildlife biologist Doug Smith, who led the park’s wolf program from 1995 until his retirement in 2022. He said that the reduced elk population boils down to three factors: carnivores, people and climate.

Human hunting, which killed more elk than wolves between 1995 and 2004, has declined, allowing more elk to survive outside the park in winter, said Smith, adding that warming winters are also luring elk into snow-free valleys north of Yellowstone. “Forty years ago, 80 percent of the elk herd wintered inside the park,” he said. “Now 80 to 90 percent winter outside the park.”

Decades of research shows that elk generally eat aspens in winter when other foods are scarce.

The population of the northern Yellowstone elk herd over 100 years. Credit: Yellowstone National Park

The population of the northern Yellowstone elk herd over 100 years. Credit: Yellowstone National Park

Smith emphasizes that predators have been a fundamental driver of the change in elk numbers and distribution, and that wolves are one of the park’s most important predators.

The popular video, “How Wolves Change Rivers,” says that fear of wolves “radically” changed elk behavior by making them avoid aspen thickets and steep riverbanks where they might become an easy meal. Some studies from the 2000s supported that conclusion, but more recent research has sowed doubt on this idea.

A 2024 study compared the likelihood that an aspen would be eaten by elk to where wolves kill elk, where wolves spend most of their time, and eight other variables that could show whether an area was unsafe for elk. The results showed little correlation between aspen browsing and the risk of wolf predation.

“If elk are avoiding wolves at those risky sites, they’re going back at a different time of day and still eating the aspens,” said study lead author Elaine Brice, a researcher at Cornell and a former PhD student in MacNulty’s lab. “It’s not at a big enough timescale to push them off of aspen in a way that will be meaningful for aspen growth.”

Brice’s analysis identified the single best predictor of aspen browsing: the number of elk in a certain place at a certain time. Wolves may indirectly protect aspens by suppressing elk populations, but not by scaring them away from specific patches, she said.

“Elk population dynamics are extraordinarily complex and you really can’t pin elk numbers to any one thing.”

doug smith, former project leader, Yellowstone Gray Wolf Restoration Project, Yellowstone National Park

Brice, who has also published research suggesting that the rate of aspen recovery has been exaggerated, said aspen recovery could take many decades. In addition, wildfire stimulates aspen growth, and many stands might grow back stronger after the next major fire resets the forest.

Aspen recovery might also be limited by record-high bison populations that trample and eat aspen sprouts in some areas, according to Painter.

MacNulty says the future of aspens in northern Yellowstone is far from certain. Research modeling the climate of Yellowstone indicates that most of the Northern Range might be too hot and dry for quaking aspens by the year 2100.

Regardless of what the future holds for the iconic aspen trees, a number of scientists believe the story has stepped over the data. “It’s undeniable that there has been some benefit to wolf reintroduction,” Bergeron said. “But the narrative that wolves are a kind of silver bullet that saved the aspen in Northern Yellowstone is oversimplified.”

An aspen stand in 1977 without any new sprouts growing. Credit: J. Schmidt / NPS

An aspen stand in 1977 without any new sprouts growing. Credit: J. Schmidt / NPS