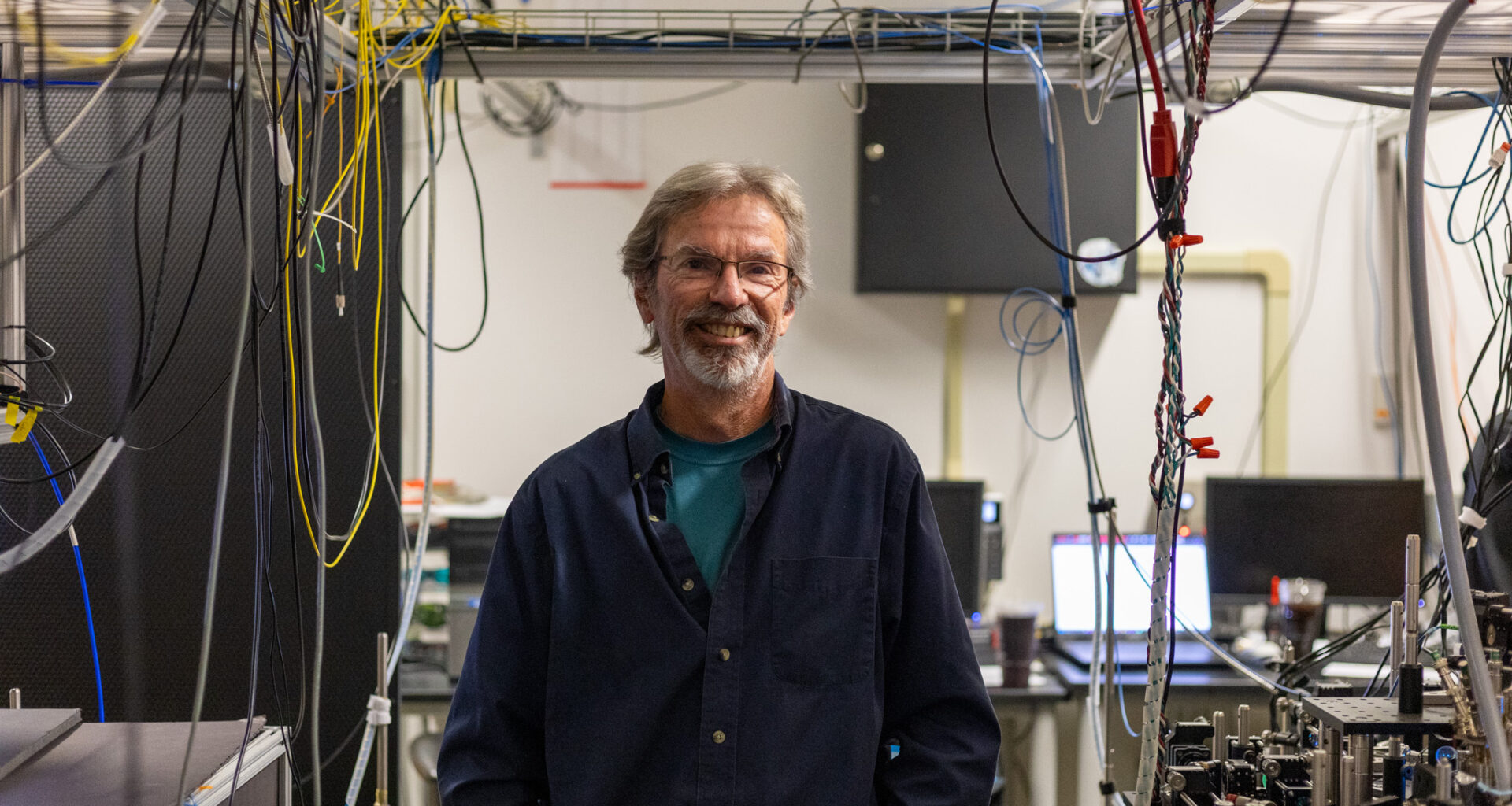

Inside an underground lab in the University of Maryland’s Physical Sciences Complex, physics professor Steven Rolston pointed toward a maze of mirrors, lenses and laser beams projected across a table.

The beams of focused light contain atoms, trapped in a vacuum chamber at temperatures similar to the conditions in outer space. Rolston and his team of student quantum researchers use these highly-controlled conditions to study how these atoms interact.

A quantum optics experiment in progress inside of the Physical Sciences Complex on Oct. 30, 2025. (Will Swearingen/The Diamondback)

A quantum optics experiment in progress inside of the Physical Sciences Complex on Oct. 30, 2025. (Will Swearingen/The Diamondback)

Rolston’s lab is one of many at this university dedicated to quantum research — a field that has drawn increased attention from the state government this year.

In January, Maryland Gov. Wes Moore announced a $1 billion initiative to make the state a “Capital of Quantum.” With more than 30 years of quantum research, this university has positioned itself as a leader in the field, according to university president Darryll Pines.

At the core of quantum computers are qubits, or “quantum bits,” which can be similar to traditional computer bits, the smallest possible unit of data. But unlike bits, which are represented as either a one or zero, qubits can exist in both binary states at the same time.

This ability to exist in multiple states simultaneously helps make quantum computing more efficient for certain kinds of algorithmic calculations.

[Gov. Wes Moore announces partnership with 2 AI firms to help streamline Maryland agencies]

But the slightest interference from the outside world, such as from light, heat or vibrations, can interrupt a quantum computer’s calculations, Rolston said. Cooling the atoms that power these computers as much as possible, as Rolston’s lab does, helps eliminate some of that noise.

The constant tug-of-war between isolating atoms from their surroundings while still exerting control over them is one of the main challenges in building a quantum computer, Rolston said.

But ask the scientists researching quantum technology what its practical use is, and the answers get fuzzy.

“They can’t necessarily tell you what quantum is going to be good for,” said Gretchen Campbell, who in July became this university’s first associate vice president for quantum research and education.“We know [it’s] going to be good for something, but we don’t know what it’s going to be, or exactly when it’s going to be.”

A piece of machinery inside of the Physical Sciences Complex on Oct. 30, 2025. (Will Swearingen/The Diamondback)

A notebook lays open inside of a laboratory in the Physical Sciences Complex on Oct. 30, 2025. (Will Swearingen/The Diamondback)

Norbert Linke, an associate physics professor and director of the National Quantum Laboratory at this university, envisions a not-too-distant future where quantum computers work alongside conventional machines in data centers, handling computationally intensive tasks.

Linke believes researchers in fields such as physics and materials science could be the first to adopt specialized applications before quantum reaches mainstream audiences.

[Prince George’s County data center task force emphasizes community input in new report]

Campbell, who spent several years coordinating quantum policy at the White House before taking her role at this university, said one advantage of quantum is its bipartisan support, and she expects that to continue.

“It’s one of those things that everybody still agrees on,” Campbell said.

Even as the Trump administration proposed substantial cuts to the National Science Foundation in May, funding for quantum and AI research was explicitly preserved.

As quantum receives more investments, researchers say the question becomes whether it can deliver practical applications before expectations outpace reality. According to Rolston, there’s some tension between the slower pace of academic research and the faster promises of the quantum industry.

“There’s a lot of hype in the quantum world, just like there is in AI,” Rolston said. “The hype tends to come from industry rather than academia, because industry is chasing investment money.”

But researchers at this university haven’t let the hype get in the way of their work studying quantum technology and its potential applications.

“My hope is that in the next five years, let’s say, we start to see applications that actually have sort of an economic value,” Campbell said.