Pressmaster/Shutterstock

The 1980s had a pop-culture zeitgeist that lesser decades can only envy (looking at you, aughts). Prosperous for most of the decade, the United States cranked out movies with big ideas, new special effects, and cultural staying power: “’80s movies” makes conceptual sense in a way that “2010s movies” doesn’t. VCRs had become affordable during the previous decade, meaning that films didn’t have to be consumed just at theaters or when they happened to be on TV. Consumers could buy or rent tapes, enjoying films at home when they felt like it and “catching up” on anything interesting they hadn’t seen in theatres during its initial run. Nearly everyone had access to the movies, and that meant they formed an important part of the shared culture.

Horror, comedy, drama, and the reborn romantic comedy all saw evergreen new films during this decade of power. Where would American culture be without aliens flying on bicycles, good-looking teenagers dying in droves in summer camps, and whimsical women feigning the throes of passion in crowded delis? Thanks to ’80s movies, we never need to find out.

Red Dawn

In 1984, the Cold War was still running reasonably hot, nuclear weapons were on hair triggers (one man even saved the world from Armageddon), and the U.S. under Ronald Reagan was charging ahead with a military buildup to challenge the Soviet Union. That year saw the release of “Red Dawn,” the story of some Colorado teenagers who band together to resist the Soviet invasion of the United States. If the concept didn’t quite make sense in the context of an explicitly nuclear rivalry, the “Soviets bad, all-American teens good” messaging found a warm welcome among moviegoers. The Soviets might have had nukes, but they didn’t have the moxie and gumption of the McDonald’s-fed teenage freedom fighters portrayed in the film. Described as anti-war by its director John Milius, “Red Dawn” still blows up enough Russians to court the most jingoist moviegoer.

For film fans, the movie also stands out as an early credit for the famous faces that dominated the silver screen in coming years. Patrick Swayze, Charlie Sheen, Lea Thompson, and Jennifer Grey all notched roles in “Red Dawn” as relatively early credits, and good old Harry Dean Stanton joined them to add a bit of gravitas.

Night of the Comet

One of the classic archetypes of the 1980s was the “valley girl,” a materialistic, shallow, and almost always blonde teenage girl who cared only about clothes and boys. In 1983, the stereotype was solidified by the release of “Valley Girl,” in which the titular character falls in love with a punk played by Nicolas Cage (which is also an interesting example of a casting agent not understanding what “punk” actually means). By the next year, the stereotype was due for a shakeup, which it got with the underrated cheerleaders-vs.-zombies flick “Night of the Comet.”

In “Night of the Comet,” perhaps unsurprisingly, a comet passes close to Earth, with the unfortunate effect of turning most people into piles of red dust. A handful of people are left unscathed, while the other survivors are turned into zombie-like monsters. Two teenage sisters, one a valley girl and the other a tough-talking brunette, survive the attack. And what better way to celebrate than having a little fun in the empty streets of Los Angeles before banding together with other survivors to kill the zombies and avoid capture by evil scientists? The girls are funny, brave, and above all survivors who are much more resourceful than their bubble-headed sisters in other ’80s media.

Friday the 13th

It’s a weird thing about American moviegoers: They love seeing teenagers die. The 1980s certainly didn’t invent the horror movie, but it did solidify the slasher subgenre. You know, those flicks where a masked or unseen killer picks off smoking, drinking, sex-having teenagers (maybe people in their very early 20s) in a variety of carnagetacular ways. It all culminates with the ultimate confrontation between the killer and the Final Girl. The hedonist got to see people having fun and, often, a topless woman; the moralist got to see normal teenage rebellion and exploration punished. And if the film made money, it would spawn a series as deathless as the killer, with sequels galore driving the body count into the dozens.

One of the seminal, genre-defying slashers was 1980’s “Friday the 13th,” which established the camp counselor as the archetypal teenage movie victim. The movie sees its cast chopped, pierced, sliced, and stabbed over the course of its hour-and-a-half runtime, with the final showdown being one of the most convincing girl-vs.-killer struggles in the genre. “Friday the 13th” spawned a lucrative and successful (if not always good) franchise detailing the near-infinite misadventures of killer Jason Voorhees, but remember: He’s not the killer in the original.

The Breakfast Club

Archive Photos/Getty Images

If you wanted to, you could argue that “The Breakfast Club” is a take on gloomy French philosopher Jean-Paul Sartre’s famous short play “No Exit.” In each, a group of people who could reasonably be expected to hate each other are confined to a single room for their transgressions, and the action develops from the complexity of their interactions. Granted, in “No Exit,” it’s three people in hell, and in “The Breakfast Club,” it’s five high school students in detention, but the bones are there.

High school stereotypes were common archetypes in 1980s movies, and “The Breakfast Club” chose a classic five for its characters: The jock, the nerd, the bad boy, the weird girl, and the popular girl (played not by a blonde for once but by the ginger queen of ’80s teen movies, Molly Ringwald). Freed of the expectations these roles put on them, if only temporarily, they become friends for the duration of their detention, revealing the true selves behind the easily rattled-off list of niches they fill in the high school ecosystem. If that weren’t enough to cement its place in the film pantheon, the theme song of “The Breakfast Club” is the tearjerking New Wave hymn to friendship, “Don’t You Forget About Me.”

ET

360b/Shutterstock

It’s weird if someone hasn’t seen “E.T.,” the 1982 Steven Spielberg heartwarmer about a boy named Elliott who befriends a stranded alien with a face like a grandmotherly turtle. The film boasts a 99% critic score on Rotten Tomatoes and has spawned colossal amounts of merchandising. So much so that an actual extraterrestrial poking around in a landfill might be confused about what the vanished human race looked like. The kind little face peered out from hundreds of products: Books, toys, a famously bad video game, and even outre and arguably unethical ones like vitamins and shot glasses. It’s a good movie, but to an extent the film is secondary: The “E.T.” phenomenon is really about truckloads and shiploads of stuff.

The titanic carbon footprint of “E.T.” mania is a shame, because at its core the movie is a lovely story about friendship across cultural and linguistic differences. The little boy and the little alien like each other, help each other, and come to understand each other despite the alien mostly speaking in catchphrases. The film also makes an important point about not trusting the government: When the feds appear and commandeer the creature, their interference nearly kills both E.T. and Elliott until the kids successfully spring the alien and help him get home.

Working Girl

The ’80s loved work, or at least the idea of work. With the economy booming and the low-regulation Reagan administration in office, work, money, and “business” appeared in pop culture as reflections of the financial success and obsessions of the era. The office-set “Working Girl” (1998) showcases the idea of the high-pressure workplace of the 1980s, with the central conflict occurring when an executive takes credit for a receptionist’s good idea. They’re both women, which points to the gender dynamics of the era: More and more women were choosing careers and pursuing them ambitiously. This shift forced changes in previously male-dominated corporate environments, even as men still outnumbered women in the workplace. (And, of course, we get the blonde-vs.-brunette rivalry again, with blonde Melanie Griffith as the receptionist against the dark tresses and darker motivations of Sigourney Weaver.)

In addition to the film’s charm and its lens on the actual power struggles and gender dynamics of the 1980s workplace, the movie is also a hoot because of its inadvertent role as a time capsule. The ’80s aesthetic is on full display, with structured blazers, huge boxy electronics, and some truly startling hairstyles. Say what you will about sexism and backstabbing — sometimes the real villain is mousse.

They Live

John Carpenter has made some of the stickiest horror movies out there, but in 1988’s “They Live,” he added social commentary to the gooey mixture. Six years after the release of Carpenter’s sister ’80s horror classic “The Thing,” “They Live” offered a fun and feisty take on an alien invasion flick. Charismatic pro wrestler “Rowdy” Roddy Piper plays the nameless main character, who finds a pair of glasses that allow him to see below the plasticky surface of the world. And what he sees is a well-in-progress takeover of the world by corpselike aliens using commercialism and subliminal messages in advertising to make the public even more sheeplike.

“They Live” is bouncy, fun, and easy to identify with — even in the corporate, consumerist ’80s, no one wanted to think of themselves as a conformist. It begs for a rewatch every few years, and especially now, as chatbots and AI slop push new frontiers in creepy social engineering. At a brisk 93 minutes, it’s worth it just to hear Piper deliver one of the classic screw-you lines of the era: “I have come here to chew bubblegum and kick ass … and I’m all out of bubblegum.”

Wall Street

Sunset Boulevard/Getty Images

Far beyond its strict geographic meaning, the term “Wall Street” implies a certain type of business and a certain type of person: A money-focused gray suit who works in finance and only thinks about cash, dollars, greenbacks, and moolah. The commerce-driven ’80s saw this cultural idea play out in real life, and one of the most memorable of its presentations was 1987’s “Wall Street.” Talk about good timing, too: The October 1987 stock market crash had rattled the economy not long before the film’s release, so people were interested in a critical treatment of stockbrokers.

Michael Douglas and about six pounds of hair gel star as Gordon Gekko, whose “greed is good” ethos came to stand as a kind of shorthand for the perceived excesses of 1980s corporate culture. While Douglas’ Gekko didn’t originate the trope of businessman-as-villain, his Oscar-winning turn certainly offered a compelling and timely take. And because everything old is new again and the world has gone far past the point of effective parody, Gekko’s famous line was quoted by U.S. President Trump — and not as a caution.

Cruising

Sunset Boulevard/Getty Images

“Cruising” generally got middling reviews. It’s suspenseful and seductive, if you’re into a certain type of gay aesthetic, and the ambiguous ending was fresher at the time than it seems today. With that said, the script is arguably weak, and its approach to the subject could read as insensitive. The story follows a serial killer targeting gay men and the straight-or-is-he detective who must go undercover in gay bars to crack the case. “Cruising” came out in 1980, right before AIDS savaged a generation of gay men, and it was targeted at general audiences. The film assumed that moviegoers would be interested in a story about gay people — some of them die horribly, while others have fun and live out, open lives.

Needless to say, “Cruising” and its take on pre-HIV gay life haven’t aged well in all regards. With that said, at least the audience is supposed to be on the side of those trying to catch the killer. Plus, you get to see Al Pacino in a leather bar.

Back to the Future

Pier Marco Tacca/Getty Images

No doubt there have been plenty of articles written about the deep significance of 1985’s time-travel adventure “Back to the Future,” but this isn’t one of them. “Back to the Future” is, simply, extremely fun. It has cool cars, a wacky scientist, time-travel cause-and-effect hijinks, and non-threatening heartthrob Michael J. Fox in the lead role of Marty McFly (one of the best fictional names ever put to celluloid). Indeed, “Back to the Future” represents one of the best types of ’80s movies: the crowd pleaser. There’s something for everyone in the flick’s goofy but heartfelt world and its associated media, which is no small achievement for a movie that is largely about making sure your parents eventually do … you know, “it.” In today’s superhero-dominated, reboot-heavy cinema landscape, making a very popular movie from a fresh idea seems wonderfully quaint.

The original movie spawned two sequels, one of which involves a jaunt to 2015 (oh, if only we’d known), and then the series stops. The series proves that a beloved media franchise can come to a graceful end instead of rattling along, “Simpsons”-like, until the heat death of the universe. Those jonesing for more “Back to the Future” have gotten a musical version, which has been produced around the world, including on cruise ships.

Dirty Dancing

“Dirty Dancing” is an interesting specimen. It’s a relatively old movie that is itself a historical film, showing us how people in the ’80s remembered (or, more realistically, imagined) the 1950s. Set in Upstate New York at a Jewish summer resort — a type that would have been nearly extinct by the film’s release — “Dirty Dancing” doesn’t claim to be a historical document but is great at presenting vibes. If the ’50s are your parents, whom you love even though they cramp your style, the ’80s are the cute (gentile) boy who teaches you how to dance dirty. Most people have had a summer crush they pursued despite their parents, even if most of these guys, in retrospect, were no Patrick Swayze.

The film’s central image, Swayze lifting a justifiably gleeful Jennifer Grey during the film’s climactic dance number, is one of the iconic images of American cinema. It’s right up there with Scarface’s plate of cocaine and E.T. riding a bicycle through the sky. It’s so memorable and so perfect with the two actors that it’s hard to imagine the casting any other way. But reportedly, there’s a not-so-distant parallel universe in which Billy Zane holds Sarah Jessica Parker above the pleasantly scandalized audience.

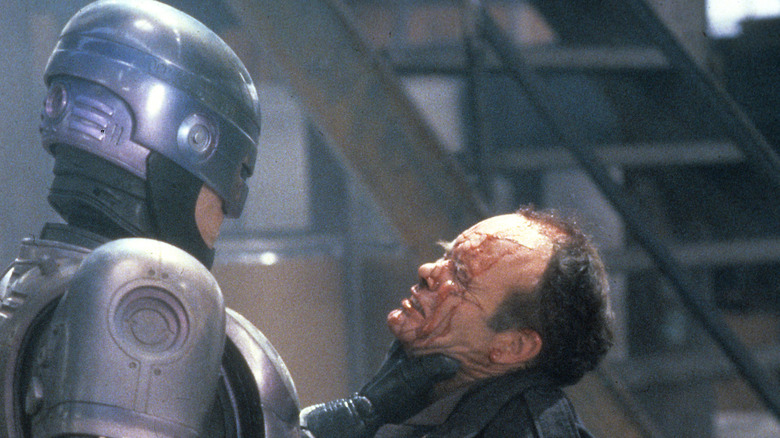

RoboCop

Orion Pictures/Getty Images

That “RoboCop” was released in 1987 is in some ways surprising. The movie does have a classic retro-futuristic look of “how the past imagined the future.” Yet the main themes — violence in policing, the true cost of “law and order,” money’s role in governance, and automation — have stuck around as key concerns in the subsequent decades. In addition to its various thought-provoking questions, this action thriller also holds up as an exciting watch that even boasts a few solid laughs.

The basic idea is that “something must be done” about crime in a near-future Detroit, and it would be great if the solution made certain people a lot of money. When a policeman is nearly killed on duty, his damaged body has a robot shell constructed around it, making him the prototype of the titular RoboCop. Is there a human core lurking under the chrome and code? Sure, American science fiction was asking that question of man-machine hybrids before “RoboCop” and seems poised to go on wondering. But the then-cutting-edge effects, satire, and good old extreme violence of “RoboCop” mean it remains a must-watch for both those dreading and those looking forward to the robot apocalypse.

When Harry Met Sally

Bonnie Schiffman Photography/Getty Images

Even if “When Harry Met Sally” weren’t a well-crafted movie, it would have its place in pop culture for the moment when Meg Ryan’s character pretends to achieve orgasm in a delicatessen. (She’s trying to prove a point — the pastrami isn’t that good.) While romantic comedies have been around for as long as movies have existed, the genre occasionally has to be reinvented like everything else. And in 1989, “When Harry Met Sally” polished and modernized the genre in advance of its ’90s successes.

To a modern viewer, some of the beats of “When Harry Met Sally” can seem trite, but that’s at least partially because effectively every rom-com since has been made by someone who saw this movie. There’s a meet-cute, a reunion against the odds, hijinks, and some dated hemming and hawing about if (straight, of course) men and women can ever be “just friends.” Also, everyone lives in Manhattan and apparently has enough money to do so. But look past the less credible, less modern aspects, and you get to the crux of a successful romance movie: We meet these two people, and we see why they fall for each other. It’s a basic idea, but it works. “When Harry Met Sally” reminded a generation that sometimes it’s nice to spend a couple of hours watching generally well-meaning people fall in love.