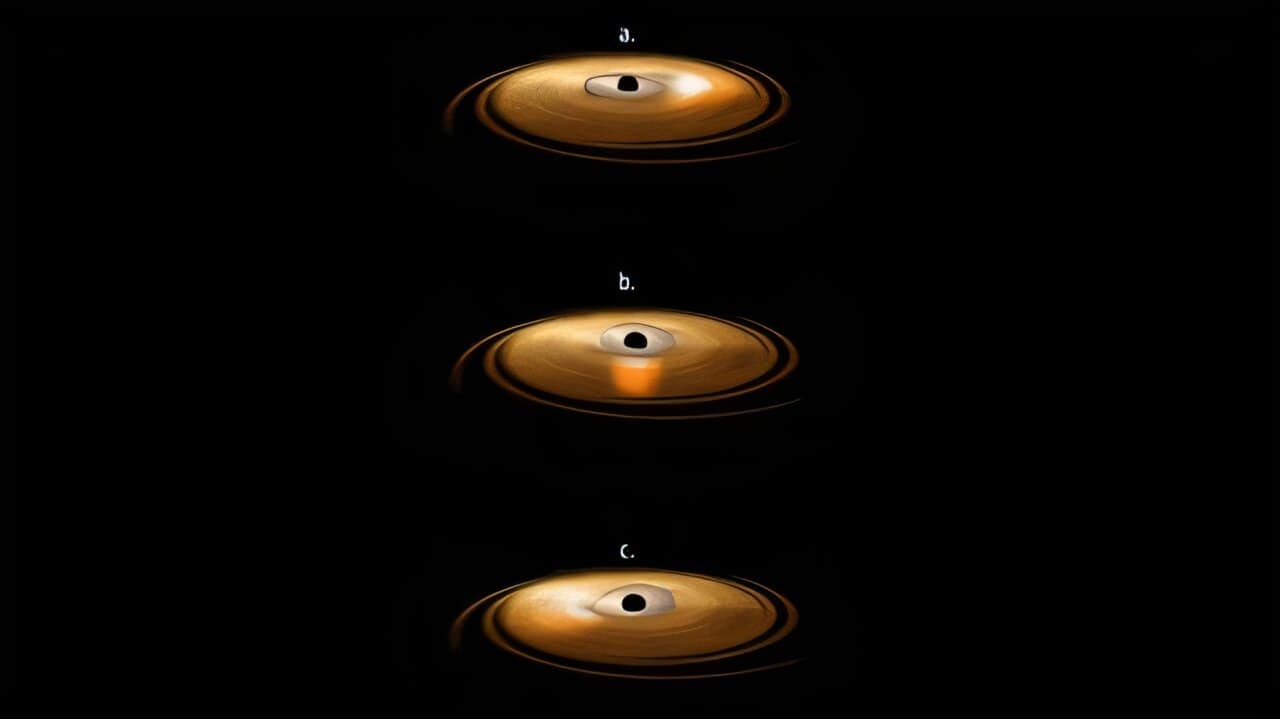

An artist’s impression depicts the accretion disk surrounding a black hole, in which the inner region of the disk wobbles. In this context, the wobble refers to the orbit of material surrounding the black hole changing orientation around the central object. Credit: NASA

An artist’s impression depicts the accretion disk surrounding a black hole, in which the inner region of the disk wobbles. In this context, the wobble refers to the orbit of material surrounding the black hole changing orientation around the central object. Credit: NASA

For more than 100 years, physicists have known — at least on paper — that spinning black holes should stir the universe around them. Now, thanks to the violent death of a distant star, astronomers have finally watched that cosmic stirring happen in real time.

The event unfolded when a star wandered too close to a supermassive black hole and was torn apart in what astronomers call a tidal disruption event, or TDE. The aftermath, cataloged as AT2020afhd, became an accidental laboratory for testing one of the strangest predictions of Einstein’s general theory of relativity: that massive, rotating objects can drag spacetime itself into a slow-motion whirlpool.

By tracking rhythmic flickers in X-rays and radio waves from this stellar wreckage, scientists report the clearest evidence yet that a black hole is twisting the fabric of spacetime around it — a phenomenon known as Lense–Thirring precession.

When a Star Becomes a Spacetime Tracer

Tidal disruption events are messy by nature. As the doomed star stretches and shreds, its gas forms a glowing disk around the black hole. Sometimes, that disk also launches narrow jets of matter that shoot outward at near-light speed.

AT2020afhd turned out to be special.

Astronomers watching the event noticed that its X-ray light brightened and dimmed dramatically — by more than a factor of ten — on a regular schedule. Every 19.6 days, the signal repeated. Soon after, radio telescopes picked up a matching rhythm.

The key detail wasn’t just the timing. The X-rays and radio waves wobbled together.

“Our study shows the most compelling evidence yet of Lense-Thirring precession — a black hole dragging space time along with it in much the same way that a spinning top might drag the water around it in a whirlpool,” said Cosimo Inserra of Cardiff University, a co-author of the study.

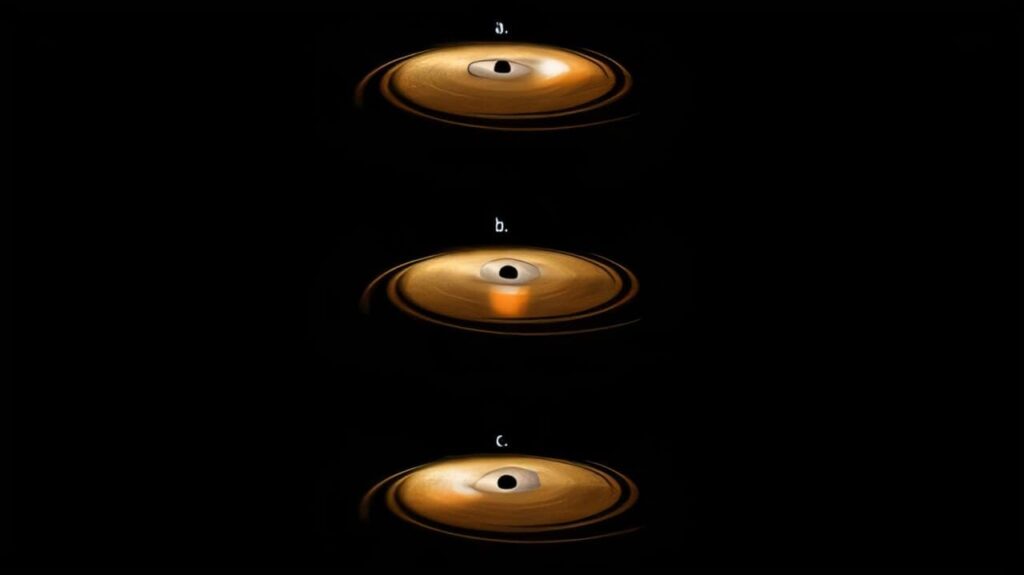

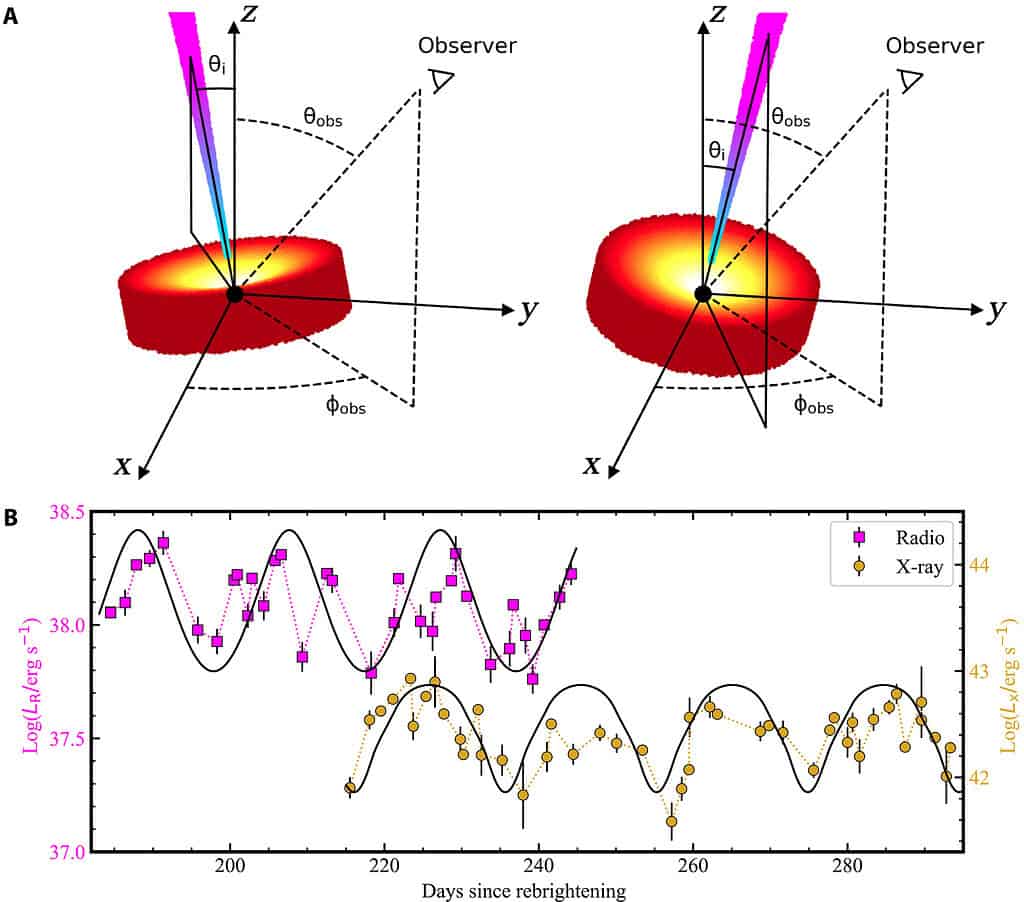

The disk-jet precession model. Credit: Science Advances (2025).

The disk-jet precession model. Credit: Science Advances (2025).

That synchronized wobble told scientists they weren’t just watching random flickering. They were seeing the entire system — the disk of stellar debris and the jet blasting outward — slowly change orientation as spacetime itself twisted under the black hole’s spin.

To catch this behavior, the team combined data from NASA’s Neil Gehrels Swift Observatory, which monitors X-rays, with radio observations from the Karl G. Jansky Very Large Array and other facilities. Earlier TDEs simply weren’t observed often enough in radio waves to reveal this kind of short-term pattern.

Why This Matters Beyond One Black Hole

Einstein first hinted at this effect in 1913. A few years later, Austrian physicists Josef Lense and Hans Thirring worked out the math. But seeing frame-dragging near a black hole has proven notoriously hard.

Closer to home, satellites have measured tiny versions of the effect around Earth. Near black holes, the effect should be enormous but also buried inside chaos, thereby challenging to observe.

This study cuts through that chaos by using the star’s remains as a tracer. As the accretion disk precessed, its projected area changed, modulating the X-rays. As the jet swung toward and away from Earth, its radio brightness rose and fell. Together, they traced the invisible geometry of warped spacetime.

“This is a real gift for physicists as we confirm predictions made more than a century ago,” Inserra said. “Not only that, but these observations also tell us more about the nature of TDEs — when a star is shredded by the immense gravitational forces exerted by a black hole.”

The analysis also hints that the black hole involved may not be spinning especially fast. Modeling suggests a relatively modest spin, which challenges assumptions that dramatic jets always require extreme rotation. That insight feeds into a broader debate about how black holes launch jets at all — whether spin, magnetic fields, or the structure of the disk matters most.

There’s a bigger takeaway, too. Tidal disruption events evolve over months, not millennia. That makes them rare chances to watch black hole systems change in something close to real time. The authors argue that future X-ray detections of rhythmic flickering could serve as alerts, prompting rapid radio follow-up to catch more spacetime whirlpools in action.

By showing that a black hole can literally drag spacetime around with it, AT2020afhd transforms an abstract prediction into an observed phenomenon. It also reminds astronomers that the universe still hides some of its strangest behaviors in moments of cosmic violence.

As Inserra put it, reflecting on the discovery, “It’s a reminder to us, especially during the festive season as we gaze up at the night sky in wonder, that we have within our grasp the opportunity to identify ever more extraordinary objects in all the variations and flavors that nature has produced.”

The findings appeared in the journal Science Advances.