US scientists have taken a major step towards supplying hospitals and treatment facilities with safer chlorine-free water disinfection by identifying why promising ozone-generating catalysts degrade over time.

The University of Pittsburgh researchers collaborated with colleagues from Drexel University and Brookhaven National Laboratory (BNL) to uncover key design principles for catalysts that generate ozone, a disinfectant, on demand.

Using quantum chemistry, the team found how microscopic defects on catalyst surfaces simultaneously enable ozone production and trigger the corrosion that shuts it down. The findings showed them how to design longer-lasting, chlorine-free water treatment systems.

“This work is a testament to how fundamental science and engineering come together to answer long-standing questions and concoct new routes to improved water and sanitation technologies,” John Keith, R.K. Mellon Faculty Fellow at the University of Pittsburgh, said.

Hidden catalyst damage

Chlorine is the dominant disinfectant for municipal drinking water, hospitals, and industrial facilities. However, this highly reactive, yellow-green halogen element has major drawbacks.

Not only is it hazardous to transport and store, but it can also form potentially carcinogenic byproducts when it reacts with organic matter. Ozone, on the other hand, is a powerful disinfectant that breaks down into oxygen, leaving no long-term chemical residue.

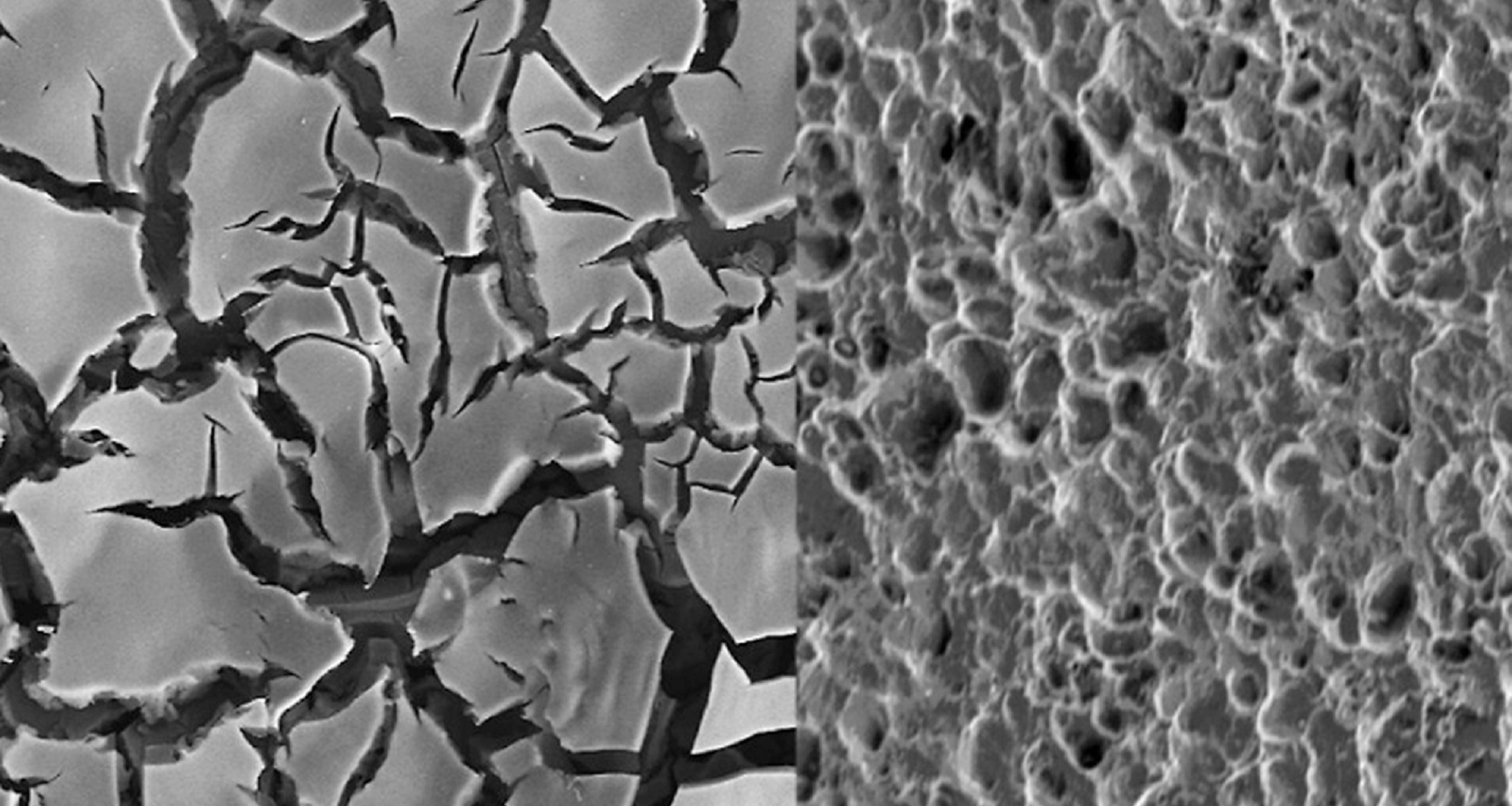

With the right catalyst, water electrolysis can produce safer, sustainable ozone, but limited understanding of how ozone-forming catalysts work has hindered progress. By pinpointing surface defects that boost ozone production or cause corrosion, the team identified traits needed for stable next-generation catalysts.

“Under extreme electrolysis conditions, exciting chemistry can start happening, but catalysts can also start breaking down quicker, too,” Keith stated in a press statement. “In the oxide-based catalysts we have studied, what forms ozone is paradoxically also suppressing its formation.”

Once the researchers understood that the same surface features driving ozone formation also accelerate catalyst breakdown, they set out to design ozone-generating sites that avoid corrosion.

Ozone without chlorine

Nickel- and antimony-doped tin oxides (NATO) have been considered the safest and most cost-effective option for electrolysis-based ozone generation. However, they degrade too quickly for widespread use.

Computational work by Lingyan Zhao, a former chemical engineering PhD student, offered clues as to why NATO catalysts break down quickly. Zhao’s analysis was validated through extensive experiments led by Rayan Alaufey, a PhD student and Drexel University researcher.

Alaufey examined how different surface structures influenced ozone output and degradation rates. The results showed that catalyst performance is defined on a core trade-off between activity and stability, which future designs must carefully control.

The team believes their findings could have significant implications for water treatment. Ozone-based disinfection systems that generate the gas directly in water could eliminate the need to transport and store hazardous chemicals.

The novel approach could reportedly improve safety across hospitals, municipal facilities, and remote installations. It could also reduce the harmful byproducts linked to chlorine-based treatment.

The study has been published in the journal ACS Catalysis.