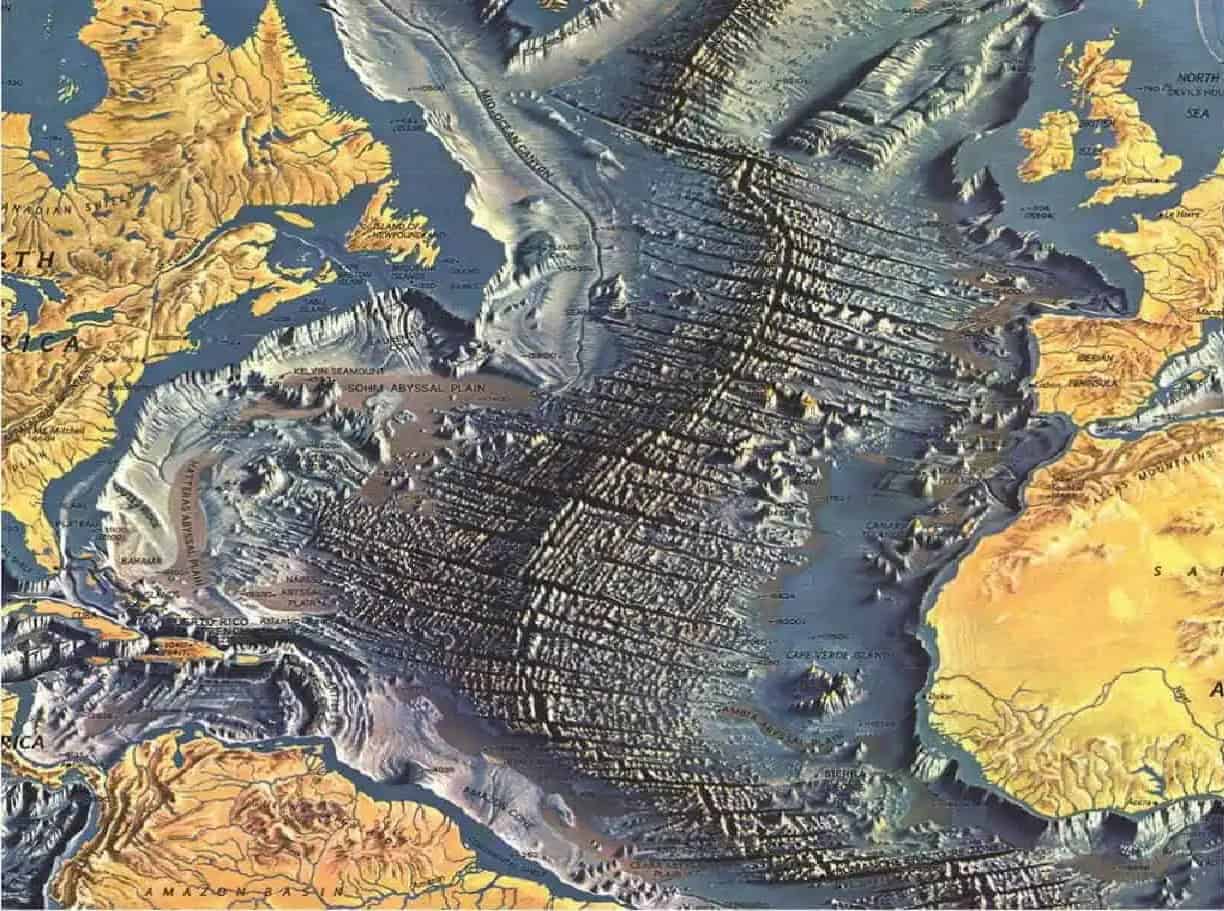

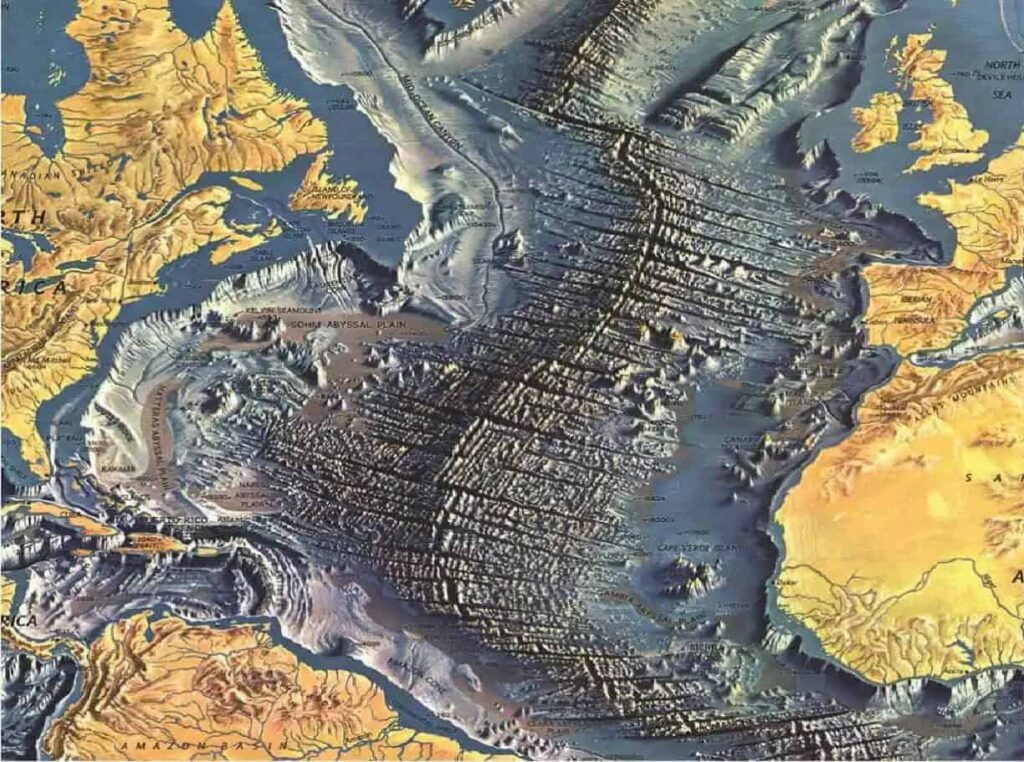

Part of the map created by Tharp and Heezen and donated to the Library of Congress.

Part of the map created by Tharp and Heezen and donated to the Library of Congress.

In the mid-20th century, when people looked at a map of the world, they saw the familiar continents surrounded by vast, featureless oceans. Beneath the waves, the ocean floor was largely unknown — an uncharted territory, hidden from view. That all changed thanks to the work of Marie Tharp.

Tharp was a pioneering cartographer and geologist whose meticulous maps of the Atlantic Ocean floor revealed the unseen. In so doing, she unlocked one of the most significant scientific revolutions of the century. In the process, however, she had to battle a lot of sexism in a field overwhelmingly dominated by men.

A Woman Mapmaker in a Man’s World

In the 1940s, geology was a boys’ club. Women were rarely accepted in the lab and almost never allowed on field expeditions. But Tharp was determined. After a string of unfulfilling jobs, she partnered with oceanographer Bruce Heezen at Columbia University.

They formed one of the most significant collaborations of the 20th century, though the division of labor was stark: Heezen went to sea, and Tharp stayed behind.

Heezen collected sonar data from ships that crossed the Atlantic Ocean. At the time, this was a new World War II technology developed to detect submarines. Sonar sent sound waves to the ocean floor and measured how long it took for the waves to bounce back, giving scientists their first look at the contours of the seabed. The data, however, was just a string of numbers and graphs — without someone to translate it into a visual format, it was difficult to interpret. It was Tharp’s job to translate that noise into a landscape.

Marie Tharp in 1968. Image via Wiki Commons.

Marie Tharp in 1968. Image via Wiki Commons.

Her role was comparable to that of female scientists who worked largely behind the scenes at NASA. She began meticulously plotting thousands of data points, a painstaking process that required a mix of mathematical skill and artistic intuition.

“Tharp, like these women, had a talent for visualizing data, something we take for granted today but required real geometric intuition before the widespread use of computers,” Hasier said.

In the process of her mapping, what she uncovered beneath the ocean’s surface would change geology forever.

The Mid-Atlantic Ridge and A New Age of Geology

As Tharp sketched the profiles of the Atlantic floor, she noticed a pattern. A continuous, jagged ridge ran right down the center of the ocean. Inside that ridge was a deep V-shaped valley. This was the Mid-Atlantic Ridge, a mountain range thousands of miles long. But the valley—the rift—was the smoking gun. Tharp realized the rift meant the ocean floor was pulling apart.

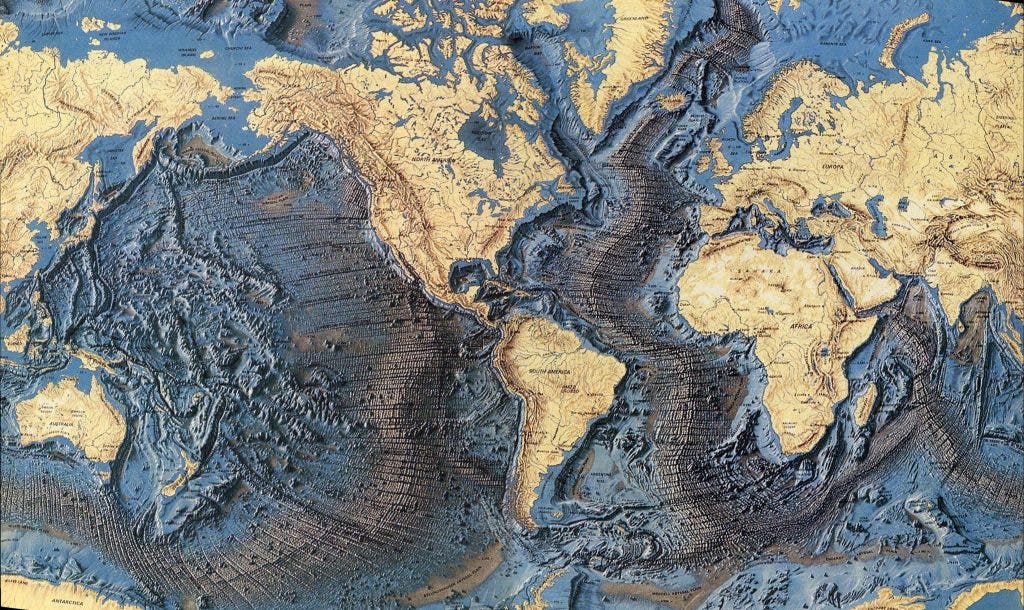

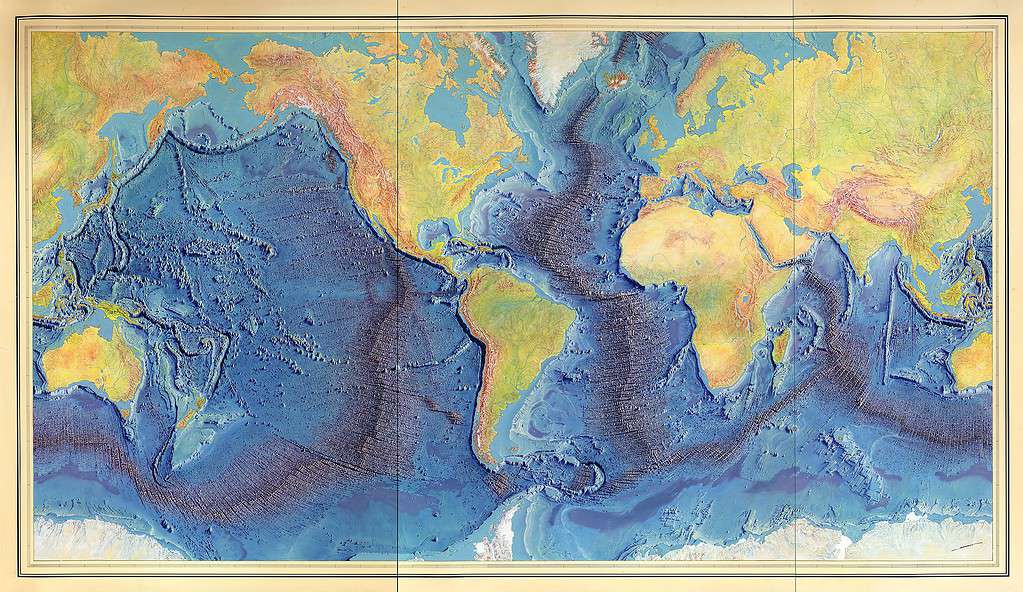

Painting of the Mid-Ocean Ridges by Heinrich Berann (1977) based on the scientific profiles of Marie Tharp and Bruce Heezen.

Painting of the Mid-Ocean Ridges by Heinrich Berann (1977) based on the scientific profiles of Marie Tharp and Bruce Heezen.

At the time, there was no theory of plate tectonics. Geologists were not in agreement as to what forces were driving geological evolution, and Tharp’s findings were extremely significant.

Decades earlier, in 1912, German scientist Alfred Wegener proposed that continents were once a single landmass that had drifted apart. This was the theory of continental drift, but the scientific community mocked Wegener because he couldn’t explain how massive continents moved.

This find was a smoking gun. It was exactly the kind of evidence that could support the controversial theory of continental drift.

“Tharp’s work certainly provided evidence and weight to the theory of plate tectonics, but her work is really about seafloor spreading, which occurs at the mid-ocean ridges that she was the first to map,” says Paulette Hasier, chief of the Geology and Maps Division of the Library of Congress.

But when she presented these findings to Heezen in 1952, he didn’t applaud. He dismissed her data as “girl talk.” It took a year of re-examining the charts before Heezen finally admitted she was right.

A Fierce Fight For Acceptance

Marie Tharp was not one to give up easily.

She stood by her interpretation of the data, refining her maps and gathering even more data. Faced with this evidence, Heezen gradually started to accept her interpretation. But convincing the broader scientific community would prove more difficult. The idea that continents could drift was still controversial. Furthermore, many geologists believed that the ocean floor was flat and featureless, as had been taught for decades.

But Tharp and Heezen had an idea. They turned not only to science to help their project, but also to art.

In the 1950s, the two collaborated with Austrian artist Heinrich Berann to create visual representations of the ocean floor. This produced stunning maps that brought Tharp’s discoveries to life in a way that no scientific paper could. They showed the vast underwater landscapes of the Atlantic Ocean, complete with the Mid-Atlantic Ridge and its central rift.

It was stunning. The map revealed a dynamic, scarred, and textured ocean floor. It circumvented military censorship while capturing the public imagination. You didn’t need a PhD to see the rift running down the Atlantic; you could look at the painting and see the scar where the Earth was tearing itself open.

But there was another catch: because of the Cold War, the U.S. government didn’t allow topographic seafloor maps to be published for fear that Soviet submarines could use them. The artistic maps circumvented that restriction — and also had the positive side effect of being beautiful.

The beauty of these maps captured the imaginations of scientists and the public alike. And, gradually, the idea of plate tectonics — the theory that Earth’s outer shell is divided into plates that move — began to gain wider acceptance. The proof for continental drift was also a key piece of evidence for confirming the greater, overarching, theory of plate tectonics.

Tharp’s maps, and the evidence they provided, became a cornerstone of the modern understanding of geology. Her work proved that the ocean floor was not static, but a dynamic, changing landscape. It showed that the Earth’s surface was in constant motion, driven by forces deep beneath the crust.

A Silent Revolution in Earth Science

For many years, Tharp’s contributions to science were overshadowed by her male colleagues. Bruce Heezen, who had originally dismissed her discovery, eventually embraced her work. But it was often his name that appeared on the scientific papers and in the media. Tharp, like many women in science at the time, worked behind the scenes, receiving little recognition for her groundbreaking contributions.

It wasn’t until later in her life that Tharp began to receive the recognition she deserved. In the 1990s, she was honored with several prestigious awards for her work in oceanography and cartography. The Library of Congress even named her one of the greatest cartographers of the 20th century.

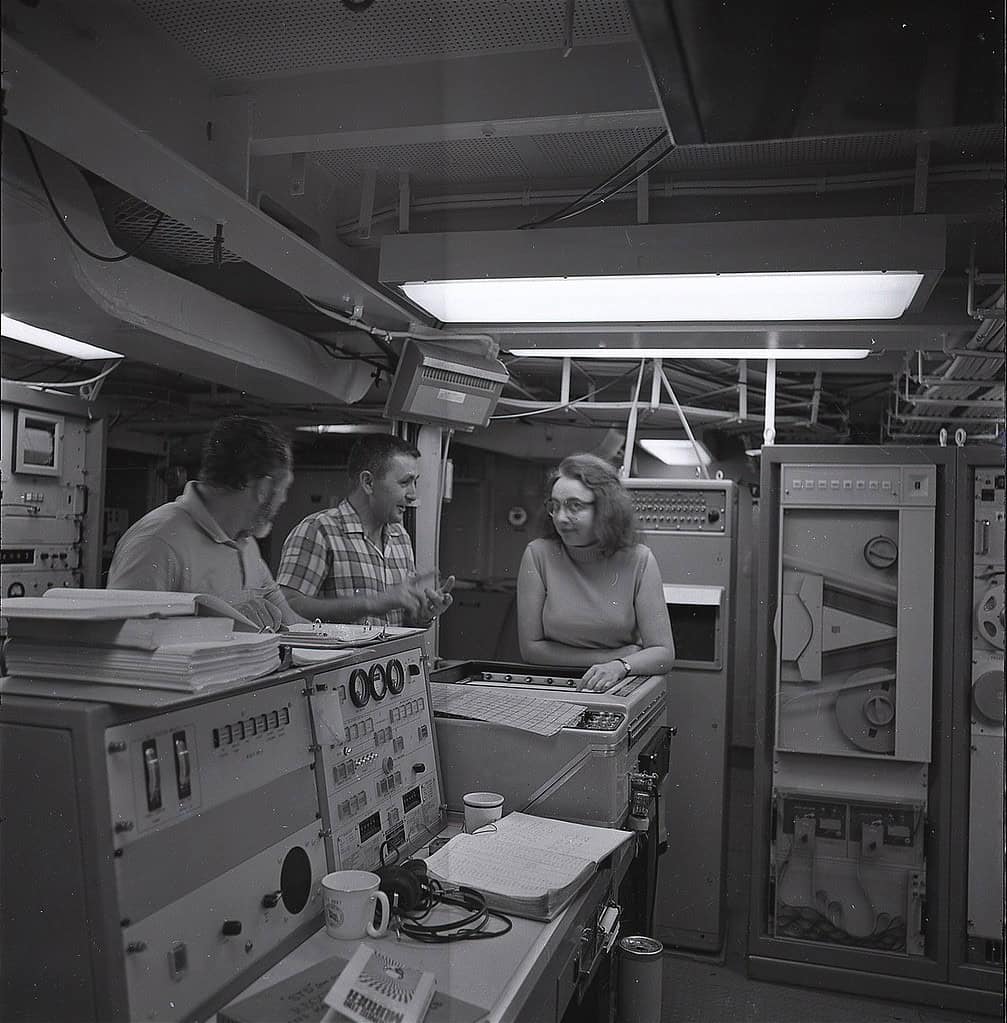

Marty Weiss, Al Ballard, and Marie Tharp conversing on the maiden voyage of the USNS Kane, c. 1968.

Marty Weiss, Al Ballard, and Marie Tharp conversing on the maiden voyage of the USNS Kane, c. 1968.

Marie Tharp’s maps of the Atlantic Ocean floor did more than just reveal an underwater mountain range — they transformed the field of geology. Her discovery of the Mid-Atlantic Ridge and the rift running through it provided the first solid evidence that the continents were moving, helping to cement the theory of plate tectonics as the foundation of modern earth science.

The impact of Tharp’s work goes beyond her maps. She showed the importance of looking at the world in new ways, of questioning established ideas, and following the evidence, even when it leads to controversial conclusions. Her persistence in the face of skepticism, and her ability to turn raw data into a compelling visual story, changed how we understand our planet.

Today, satellite and sonar technology enable us to map the ocean floor with incredible precision, but none of this would have been possible without Tharp’s pioneering efforts. Her work laid the groundwork for generations of scientists, and her maps continue to inspire new discoveries about the world beneath the waves.

A Modern Legacy

In recent years, the scientific community has moved to correct the historical oversight of Tharp’s work with significant new honors. In 2023, the U.S. Navy officially renamed a 350-foot oceanographic survey ship the USNS Marie Tharp. The renaming was particularly symbolic: the vessel was previously named after a Confederate officer, and its new title represents a firm acknowledgment of Tharp’s dominance in a field that once barred her from even stepping foot on a boat.

Her influence also continues to guide the future of oceanography. Tharp’s original maps covered vast areas, but we still have not mapped the entire ocean floor in high resolution. Inspired by her pioneering spirit, the Seabed 2030 Project, a global collaboration, is currently racing to map 100% of the ocean floor by the end of the decade. As of 2025, they have mapped roughly a quarter of the seabed, using modern multi-beam sonar to fill in the blank spaces Tharp first dared to chart.

Further cementing her status, the European Geosciences Union recently established the Marie Tharp Medal, one of the highest honors in the field, awarded to scientists who make outstanding contributions to the understanding of the Earth’s structure. These events signal that while Tharp may have been ignored in the 20th century, she will define the 21st.

This article has been edited to include recent information.