On May 23, 2023, Kelly Barta arrived at the National Institutes of Health to figure out what was wrong with her. In a sense, she already knew: She had diagnosed herself with topical steroid withdrawal in 2012, and had gone on to become the president and executive director of a TSW advocacy group. But many doctors weren’t convinced the disorder existed, and as far as Barta could tell, most researchers didn’t care enough to dig into it. The fact that the biggest funder of biomedical research in the world was even trying to decipher its biology felt like a breakthrough.

It had started with eczema when she was a child in Grand Rapids, Mich.: itchy patches in the creases behind her knees and elbows, which spread to her hands and face when she became a preteen. Her doctors managed it with moisturizers and topical steroids. That worked, but over the years, the strength of her steroid prescriptions crept upward — and one day, when she was in her late 30s, working as a musician in Atlanta, a pharmacist casually mentioned that she should be careful, these were really potent steroids, how long had she been taking this sort of stuff? Probably around 10 years, Barta replied. “Just for a second, her eyes kind of popped open, and she got this look on her face, and it made me sick to my stomach,” Barta said.

When she did stop her steroids, what had been patches of eczema here and there morphed. Now, she burned everywhere, a redness that covered almost her entire body. She was beset by a new itch, different from an eczema itch, a “bone-deep itch” rather than a superficial one. “An itch like a panic attack, an itch so intense you can’t think of anything, you literally want to claw your skin off, you don’t care if it’s bleeding. It’s indescribable,” Barta said. Her clawed-at skin oozed. She would lie naked on towels, peeling her crusted self off to take a bath every two hours. It hurt to wear clothes. It hurt to move. She couldn’t sleep. She tried the breathing exercises she’d used to get through childbirth. This lasted for years. Eventually, her 21-year marriage fell apart.

Early on, in a moment of sleepless Googling, she had stumbled on the term “topical steroid withdrawal,” or TSW. “It was like check, check, check, checking the boxes,” she said. “Even though it was a horrible realization, I just knew that was me. It all clicked into place.”

The underlying biology, though, was a mystery. The ailment was defined by symptoms and stories. Some dermatologists were skeptical. They thought it might just be eczema, roaring back with a vengeance when someone stopped treatment. That drove the TSW community up the wall: They had lived with eczema, they knew what it felt like, this felt different. Other physicians worried that these activists were scaring patients away from medications that could be enormously helpful. Activists retorted that they weren’t against steroids, just against their wanton use.

Into this disputed terrain stepped Ian Myles, an allergist-immunologist at the NIH. The vast majority of the agency’s $48 billion annual budget is sent out to researchers elsewhere, but about 11% stays in house, funding research on the campus itself. Myles ran one of those intramural government labs. He was the person who’d invited Barta to Bethesda, Md., to give little hole-punches of her forearms, swabs of her microbiome, and vials of her blood — to be both a research participant and a co-author. When their study of some three-dozen people came out in August 2025, the patient community saw it as a triumph: the first preliminary glimmer of evidence that TSW might be microbiologically distinct — something you could one day test for. Certain other researchers weren’t so sure. Critiques came from both TSW skeptics and TSW allies, a disagreement about how best to probe the unknown when that unknown was tearing apart people’s lives.

Kelly Barta, while she was suffering from TSW.Courtesy Kelly Barta

Kelly Barta, while she was suffering from TSW.Courtesy Kelly Barta

What both sides could agree on was that these questions needed more research. But by the time his initial study came out, Myles had already set aside the follow-up trial he’d planned. Last February, in the name of cost efficiency, the Trump administration had frozen the credit cards government scientists use to purchase lab supplies. By spring, there had been several rounds of mass federal layoffs; employees who’d previously helped with fiddly tasks were gone. Administrative requirements began taking longer. Myles wasn’t angry, just matter-of-fact about the fluctuations of his job. He didn’t want to start enrolling patients if he was uncertain about his ability to follow through. He put the study on indefinite pause.

In federal bureaucracy jargon, the term for a layoff is a “reduction in force.” It’s easy to make an acronym of it, a RIF, and pay little attention to the words themselves. But they capture the results of what has happened this year within government agencies: not only the loss of personnel but also the various disruptions to business as usual. Some argue this is a necessary correction to a bloated ecosystem. But it comes at a cost: offices and labs more limited in what they can accomplish, their forces reduced. While the sweeping termination of NIH grants to external scientists has sparked lawsuits to stop them and databases to track them, these diminished internal abilities have drawn less notice. To TSW patients, though, they’re no less maddening.

Rising eczema rates and a fight for TSW research

Myles hadn’t meant to study TSW. The whole saga started in 2019, when he happened to hear Barta speak at a Food and Drug Administration event, designed so that skin researchers could learn from patient perspectives. “I had never heard of it in my entire medical training. Initially, it sounded insane,” he said. But when he looked online, he noticed a discrepancy: posts about #topicalsteroidwithdrawal with hundreds of millions of views, but not much in the way of microbiological research. “Whatever was going on, there wasn’t a mountain of evidence against these people, right?” he said.

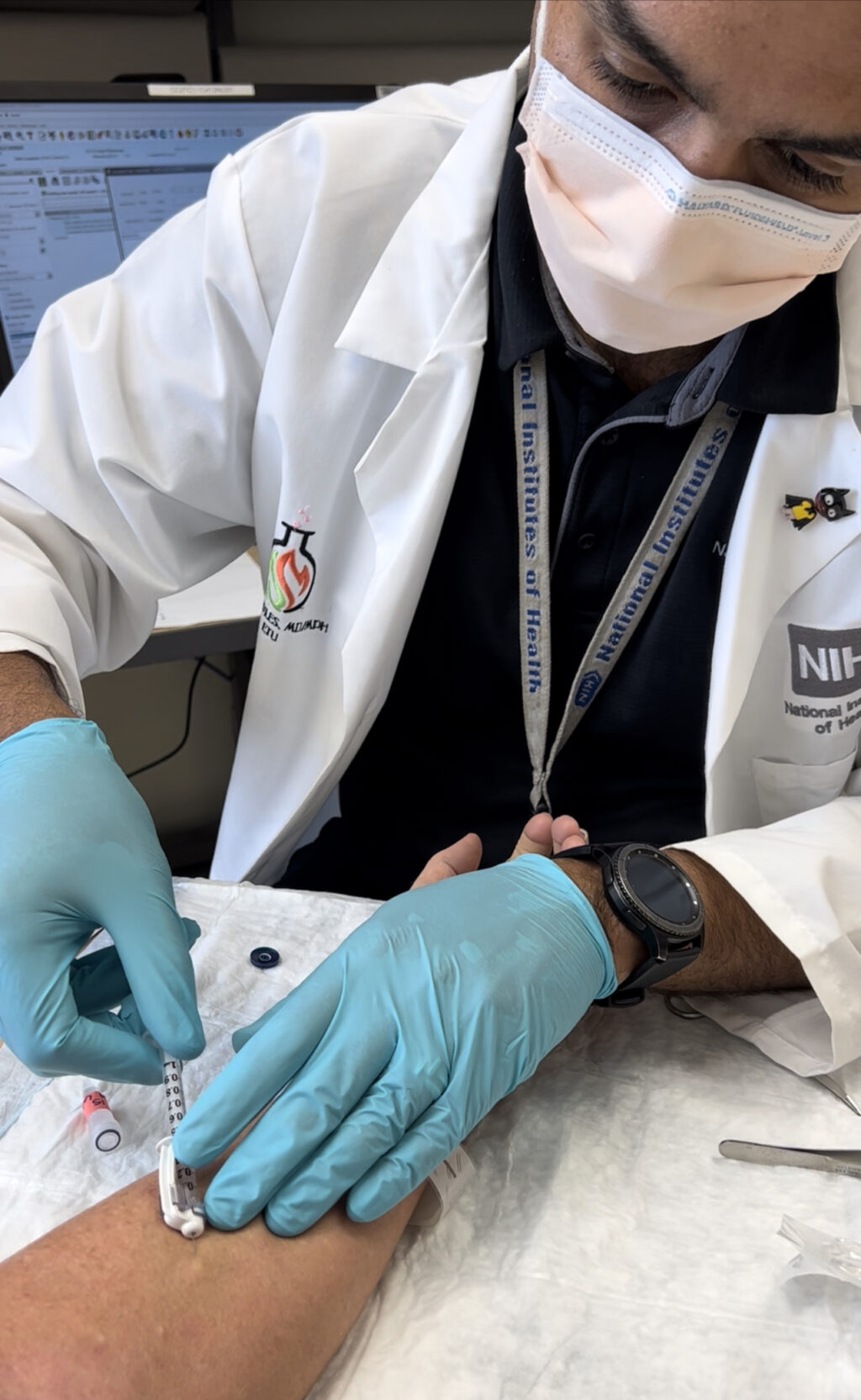

Myles takes a skin biopsy from Barta’s forearm as part of his study at NIH.Courtesy Kelly Barta

Myles takes a skin biopsy from Barta’s forearm as part of his study at NIH.Courtesy Kelly Barta

Still, he wasn’t the researcher they were looking for. He had other projects to tend to. He was interested in rising eczema prevalence. Among American children, it had jumped from 7.9% to 12.6% between 1997 and 2018. That had deep implications. Dermatologic health is a bellwether for our relationship with the outside world. It underpins the comfort that allows us to be functional, but also hints at other bodily goings-on — and childhood eczema is among the biggest predictors of food allergies. Unlocking the driver of these rashes might help explain our age of hypersensitivities.

Myles suspected that the root of the problem lay in pollutants, toxins, and detergents disrupting our microbiomes, and he was busy looking into that hypothesis, swabbing skin to see what bacteria were living on it, spraying on different species to see if that might help. He was speaking at an eczema conference about that work in 2022 when Barta came up to him; he recognized her as “that lady with TSW.” She said she wanted to meet with NIH officials about organizing research into TSW. He put her in touch with government employees involved in underwriting skin studies, who in turn referred her to a network of NIH-funded dermatologic researchers at various universities — a kind of royal court of American eczema scientists. Initially, their response was encouraging. “I gave them a whole presentation, and they’re like, ‘Oh yeah, this is really compelling,’” Barta recalled. “They ended up publishing a paper calling for more research.”

But the research itself — the nitty-gritty microbiological study that Barta was waiting for — never came.

“It became painfully obvious that every lab that had the resources to do this work did not have the interest to do it,” said Myles. There was a pattern there. The contestedness of a contested illness can feel like a trap, gripping tighter the more you try to extricate yourself. With no official diagnostic criteria, some doctors aren’t sure there’s a diagnosis there at all. But the research that might help establish diagnostic criteria depends on a certain level of recognition: not only an openness to the idea, but a conviction that this is worth spending precious time and funding on. For patients, that creates a catch-22. The less they’re listened to, the more insistent they become, and the more insistent they become, the less doctors are inclined to listen.

Science

More in American Science, Shattered

“Nothing is being done, and then they get angry, and then there are echoes of less scientifically grounded arguments,” Myles said. “When they start saying, ‘the pharmaceutical companies are corrupting medicine,’ or ‘the FDA isn’t really doing anything to try to help us,’ or ‘everybody’s just out for the money and covering their butt,’ you start to hear echoes of chem trails and whatever. But that’s not them, right? They’re making good points.”

He didn’t think there was some profit-motivated Big Pharma cover-up. Steroids were old drugs, patents long since expired, now sold as cheap generics. Yes, they were prescribed often, and companies got revenue from them. To him, the denials and dismissals likely had a simpler, less nefarious explanation: experts’ fear of not knowing, of having been wrong, of having potentially caused harm, of going against the professional grain.

On TSW social media, you could see that some people, frustrated with mainstream medicine, had turned elsewhere, willing to try anything. Had anyone tried CBD? Had anyone tried fasting? What about ivermectin? Red-light therapy? Restricting water intake and moisturizer use? What about one specific clinic in Thailand offering cold atmospheric plasma? A possible association with the fringes didn’t exactly draw researchers in. Barta had heard from one doctor who’d backed off from publishing on TSW because she didn’t want to cloud her kid’s future in dermatology.

Myles was freer from those sorts of pressures than most. As an intramural NIH researcher, his lab had an annual budget. While every project still had to go through multiple approvals, he wasn’t fighting to convince reviewers that an idea was worth funding. Plus, he wasn’t a dermatologist. “I’m not in their pecking order,” he said.

Nor was he afraid of scientific conflict. In 2023, he’d self-published a book about “how population genetics failed the populace.” In both the academic press and on YouTube, he has called out specific other researchers for what he sees as scientific racism. “Keep in mind, I’m a guy who’s busy spraying people with bacteria to try to treat their skin disease, so everybody knows this guy does things a little differently,” he said.

If the royal court of American eczema research wouldn’t take this on, Myles thought, he might just do a little study himself. When he wrote to Barta about the idea, she began to cry.

Barta poses with her two children.Courtesy Kelly Barta

Barta poses with her two children.Courtesy Kelly Barta

Steroids, World War II, and a medical mystery

The race to develop steroids began as a matter of national security. In 1929, rheumatologist Philip Hench noticed that patients’ arthritis improved dramatically when they became sick with jaundice. Something similar happened, he observed, when patients experienced pregnancy or surgery — as if the body, under stress, was producing its own inflammation-fighting elixir. “Substance x,” Hench called it. The hypothesis he and chemist Edward Kendall hit on were hormones produced by the adrenal glands, which perch on the kidneys like little woolen hats.

But it was World War II that transformed this research into an urgent patriotic quest. Rumor had it that the Nazis were importing cow glands by the submarineful from Argentina; there were fears of Luftwaffe pilots, hormone-boosted to withstand higher altitudes. Apocryphal as such stories might’ve been, American science would not be outdone. When the National Research Council set priorities for government-funded wartime research, one was understanding what Hench had called “Substance x.” By 1944, a candidate had been synthesized from ox bile.

The war ended. The portfolio of studies jump-started for military ends was transferred to the burgeoning NIH, part of a plan to make the U.S. into a biomedical mecca — economic and technological dominance driven by nerds. Like many other wartime discoveries, corticosteroids had a peacetime use. When the stuff was injected into rheumatoid arthritis patients, the results seemed nothing short of magical. In 1949, there was a presentation at the Mayo Clinic with motion pictures: “On the screen the gathering saw fourteen men and women, some bedridden, some in wheel chairs, stiff of joint and ridden with pain, get up and walk briskly,” The New York Times reported. One man — previously too tender to be touched — had improved “to the point where he could dance a jig.”

Patients clamored for cortisone. There were competing patent claims. A black market emerged. But the magic was short-lived: The first patient who’d gotten treated soon found herself in a locked psychiatric ward, at turns depressed, euphoric, and psychotic. It’s a pharmacologic tenet: What separates remedy from poison is simply a matter of use and dose. Corticosteroids are a prime example. They can quell allergic reactions, soothe rashes, curb asthma attacks, quiet the nausea of chemo, forestall organ rejection, pause the autoimmune disintegration of the colon in Crohn’s disease and of the joints in lupus — and plenty more. But with prolonged systemic exposure, the side effects are just as varied, increasing risks musculoskeletal, metabolic, cardiovascular, gastric, psychiatric, and ophthalmological.

STAT Plus: Amid talk of a brain drain, some scientists leave U.S. behind

By the 1960s, the public had gotten so spooked about the potential dangers of corticosteroids that a whole group of commonly used drugs — which includes aspirin, naproxen, and ibuprofen — was named “nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs,” specifically so people wouldn’t fear them.

TSW slotted uncomfortably into this history. Steroids are a double-edged sword, but topical formulations are more localized and generally considered safer. Though there had been TSW-like case reports for decades, questions about safe dermatologic use burst into the public consciousness care of TikTok and Instagram. Some doctors warned of “steroid phobia,” which the patient community hated, because it suggested wariness about these drugs was unfounded, even pathological.

“The answer for those patients is clearly not more steroids. That’s what’s so frustrating to me,” said Peter Lio, a dermatologist at Northwestern University who both incorporates alternative practices like acupuncture into his practice and has received payments from makers of newer, nonsteroidal topical drugs. Even before his name got around as the doctor to see if you have TSW — before people began to fly from New York, California, France, and New Zealand to see him, before he was even sure he believed in the diagnosis — he thought these patients had been through a vicious cycle of overuse: Eczema not responding well to treatment, doctors prescribing more and stronger courses.

Eventually, though he knew some colleagues disagreed, he realized this didn’t really look like eczema to him. These people had “red-sleeve sign,” as if their arms had been uniformly and deeply sunburned right up to a line at their wrist. They had “elephant skin,” parts of them thickened and wrinkled like a pachyderm. They had “headlight sign,” their faces affected but for a patch around their nose and upper lip. Their temperatures were dysregulated, their lymph nodes swollen, their skin flaking like crazy. “Patients refer to it as snow,” Lio said. “They sweep it up and bring me bags of it.”

There were overlaps with other dermatologic conditions, but also what seemed to some like weird particularities. The explanation, though, remained unclear. As drugs, corticosteroids were an external reproduction of our bodies’ own fight-or-flight chemicals. They constricted blood vessels — and so stopping them might trigger a violent rebound dilation that didn’t stop when it should. Long-term use might be causing steroid tolerance, or throwing specific receptors out of whack, or impairing the skin’s ability to function as a barrier, which in turn triggered an inflammatory Rube Goldberg machine.

As a perspective paper from 2024 explained, even the most basic information was still uncertain. There was no diagnostic smoking gun doctors could use to be sure something was TSW. Risk factors included at least six months — but more often, over a year — of “inappropriate” medium- or high-potency steroid use, especially in sensitive areas like the face or genitals, though patients might quibble with some of those details. Prevalence was unknown. Onset was variable, ranging from days to months after stopping steroids. Prognosis, too, was unpredictable, with symptoms lasting months to years. It was unclear why some minority of patients got this and others didn’t, why flare-ups could differ from person to person, or what might actually help.

There was a private Facebook support group with some 27,000 members, though it was possible that some subset of those members in fact had something else. Still, it was clear that these patients were suffering. Some sequestered themselves in other rooms, hoping to spare their spouses the presence of so much agony. More than anything, they wanted these symptoms to end. But they also wanted recognition of what they were going through. On both fronts, some biological signature — a small step toward a test for TSW — could help. That was what Myles was hoping to find.

A copy of Myles’ controversial study published in the Journal of Investigative Dermatology.André Chung for STAT

A copy of Myles’ controversial study published in the Journal of Investigative Dermatology.André Chung for STAT

Searching for the biology of TSW

The idea was to bring three different groups of patients to the NIH — 16 with TSW, 10 with plain old eczema, and 11 healthy volunteers — and then run a battery of tests on their blood and skin to see if there was something that set TSW apart. In some analyses, those with TSW and those with eczema looked similar. Compared with the healthy volunteers, the swabs from both groups showed higher populations of Staphylococcus aureus and lower bacterial diversity, the skin biopsies showed more of the T cells and macrophages one might expect to see in a place with inflammation, and the serum samples showed the interleukins that help coordinate that sort of immune response. These bodies were all riled up, as if under attack.

What differed, though, between the two skin-disease groups appeared when Myles’ team looked at other molecules present in the skin biopsies. The TSW patients had abnormally high levels of vitamin B3, or niacin, and abnormally low levels of tryptophan, their paper reported. One possible explanation lay in the mitochondria, the tiny powerhouses of our cells, performing the daily alchemy of transmuting nutrients and oxygen into energy, which included breaking down tryptophan and producing niacin.

To Myles and Nadia Shobnam, the first author of the paper, it looked like a specific bit of mitochondrial machinery was overactive in TSW. That also jibed with an idea that was already in the scientific literature. When niacin was first used as an oral drug to fight cholesterol in the 1950s, it was limited by an uncomfortable side effect of making patients flush, their skin red, warm, and sometimes itchy — not so different from one common complaint in TSW.

But the study didn’t stop there. A colleague of Myles’ had casually mentioned that metformin, a common diabetes drug, blocked the specific bit of mitochondrial machinery they thought was working overtime, and an herbal supplement called berberine — “nature’s Ozempic,” according to a social media fad — had a similar chemical effect.

Myles wasn’t about to turn this pilot study into a randomized controlled trial of these compounds, but he told the participants who had TSW that they could try either of these substances on their own, and that if they did, he wanted to hear how their symptoms changed. Based on lab analyses, he helped counsel patients about which berberine vendors were actually selling what they said they were; otherwise, to him, they might as well be trying sawdust.

Three patients got metformin prescriptions from their doctors, nine ordered berberine online, and within three to five months, they tended to report improvements in the “bone-deep itch” and some clearance of their rashes, though their TSW still sometimes flared up occasionally. These results might be attributable to the placebo effect; after all, these patients’ experiences were being compared to the expected course of TSW — hardly the level of evidence doctors hope for when considering a therapy. Still, it seemed worth a shot; the TSW community was desperate. When the manuscript was ready, it contained, along with graphs and signaling-pathway charts, a few before-and-after photos.

‘Thank you for giving us credibility’

When a patient community feels ignored and gaslit by the institutions of medicine, and members of those institutions worry that patient stories aren’t entirely reliable as data, pressure builds. Every study becomes a battleground. In April 2024, Myles’ team posted the paper on a preprint server, not yet peer-reviewed. In early May, Myles broke down the results for patients on YouTube. In the comments section, the relief was palpable.

“As someone who has been going through TSW, this study has been an incredible gift, and I feel like a weight has been lifted off my shoulders. We have so much more work to do, but you just opened the door to let other reputable people such as yourself take this topic seriously,” one person wrote.

“Thank you for giving us credibility and proof of our condition,” wrote another.

Other researchers weren’t convinced this paper counted as proof, though, once it came out in the Journal of Investigative Dermatology in August 2025. To some, there was a gnarly old problem of diagnostic criteria. Though Myles had established a framework for how many symptoms a patient had to have to qualify for participation, the symptoms remained self-reported. “How do you know you are describing the same condition?” asked Eugene Tan, a dermatologist at the University of New South Wales, in Australia, who coauthored a critique of the paper. He worried that the criteria were based on a survey done by the International Topical Steroid Awareness Network, the patient advocacy group that Barta had led, and that without a less subjective diagnosis, the study results didn’t mean much. “How do you know that these patients are not primed to say stuff you want them to say? In court, you’d say, ‘leading question, your honor.’”

“The first thing I would like is for it to be determined whether topical steroid withdrawal exists in the first place,” he added in an email. He didn’t mean to dismiss the experience of TSW sufferers, but to him, compliance was the Achilles’ heel of any topical treatment, making it tough to differentiate between TSW and eczema that was poorly controlled by a drug not being taken as directed; he has eczema himself and knows how difficult such regimens are to keep. Before anything, he wanted to see a study chronicling the natural history of eczema when investigators are monitoring how and when patients apply creams.

Two researchers in the U.K., meanwhile, wrote a critique from the opposite perspective. They trusted TSW patient experiences, but they worried that this NIH study oversold its results and that the evidence for mitochondrial involvement remained “speculative.” Myles and Shobnam responded in print, claiming the letter writers had misunderstood the technical details they were picking apart.

Beneath this back-and-forth lay the very murk that scared some researchers away from this topic in the first place. Designing a TSW study could be a high-stakes puzzle; satisfying both those agnostic to whether the condition is real and those who are suffering from it was unlikely if not impossible. The combination of patient desperation and lack of scientific interest meant that there was a risk for any finding to be seen as the answer, case closed, rather than one small step in an iterative accumulation of evidence. That was the irony. Though they disagreed about what it might look like, every side in the dispute about Myles’ study wanted the same thing: more research.

Myles, a commissioned officer in the U.S. Public Health Service, poses in his uniform.André Chung for STAT

Myles, a commissioned officer in the U.S. Public Health Service, poses in his uniform.André Chung for STAT

Frozen credit cards, layoffs, shifting priorities

That had been Myles’ plan. In January 2025, even before the paper had officially come out, he was ready to request approval for a bigger berberine trial. It would’ve involved around100 people. But then, under the Trump 2.0 mandate for a slimmer, more “efficient” federal apparatus, the credit cards NIH workers used to buy supplies were temporarily frozen. Getting berberine, biopsy punches, microbiome swabs, and chemicals for molecular tests would have to wait. Plus, some of the employees involved in purchasing had left or been laid off. “When they told us, ‘OK, you can purchase now,’ you’re like, how? And so then we all had to file for what we call purchase cards. And that took several months,” he said.

These slowdowns weren’t the only reason Myles set aside his next TSW study. In October, Shobnam, the initial paper’s first author, left the NIH for personal reasons, not political ones, with the idea of potentially collecting samples from her TSW patients in New Jersey and sending them back to her old place of work for analysis. But that wasn’t certain. “My new job is purely clinical, and I haven’t had any time for research yet,” she said.

TSW was also a side project for Myles. His main research on environmental factors and eczema dovetailed with what he saw as the priorities laid out under health secretary Robert F. Kennedy Jr. He doesn’t blame the new administration or take it personally. It would not have been impossible for him to pursue more TSW research; it just would’ve been slower. With competing demands on his time, he chose the sort of science he was best at, uncertain that whatever would emerge from the follow-up trial he’d planned would warrant the hurdles involved. “The juice-to-squeeze ratio has shifted,” he said.

He’s philosophical about the fact that this is the nature of his job as a government scientist. Priorities change. Cancer moonshots come and go. Agency budgets fluctuate. Staffing numbers rise and fall. “If Secretary Kennedy came down and said, ‘Oh my God, I can’t believe a pharmaceutical is doing all this, we’ve got to research this, give this man $10 million and go do it,’ I’m not going to tell him no,” Myles said. “So I have to deal with the reality of the flip side of that. If they want to make it harder to do research, that’s also part of our existence. The administration’s priorities change, and we adapt. But it is true that part of the adaptation in this particular case is that we just can’t commit to starting an entire trial again.”

To a mind bent on smaller government, such refocusing might be a cause for celebration. It’s not as though all TSW research would stop. The two U.K. researchers who’d critiqued Myles’ study were recruiting patients to try to look for biological patterns among this patient population. They would be taking saliva samples in addition to skin and blood, to figure out whether long-term topical steroids had suppressed the body’s own production of such chemicals, which might be at the root of some of these symptoms.

Barta has, herself, a healthy suspicion of the federal bureaucracy. She’d long thought that agencies needed to be better held accountable to taxpayers. But as someone who’d spent years pushing to understand TSW, this slowdown in Myles’ lab felt like a blow. “I understand the need for a shake-up,” she said, “but it really has set things back and pushed pause and been super frustrating.”

The steroids at the center of the whole controversy had emerged from a sense that biomedical science was a patriotic public good — a boon for the war effort and for the U.S. as a whole. That in turn became a midcentury surge in research, symbolized by the behemoth that is the NIH. Knowledge production, the thinking went, could boost economies, create jobs, reduce illness, and lengthen lives. In this grand sweep, a relatively small berberine trial for a potentially rare illness may seem insignificant. The supplement was hardly the surefire cure that the TSW community was hoping for, according to those who’d tried it. Yet these ongoing steroidal questions, some 75 years after these drugs were introduced, are just one example of how science builds upon itself — and of what might be lost in weakening the structure that undergirds it. Even Myles’ critics worry about the loss of momentum that his scrapped protocol represents.

“It’s really quite sad, because science is just a tool to find the truth. Someone needed to publish this, and someone needed to critique it,” said Tan, of Myles’ initial study. The issues he’d raised were not an admonishment to stop but a reason to keep going, to look deeper. “Hopefully, he’ll respond by saying, ‘I am going to validate this, I am going to prove you wrong.’ I hope he succeeds.”