The problem facing the engineers from Arup, when they were given the sort of commission engineers from Arup do not imagine they will ever get, was the crypt.

When, 150 years ago, Antoni Gaudí began working on a new basilica for Barcelona, he had a soaring vision.

His church, the Sagrada Familia, would have towers that rose higher than any church in history. They would do so without buttresses, supported by geometry itself. He had studied, he said, the “great book of nature”. Like vast stone trees they would grow on the Catalonian skyline.

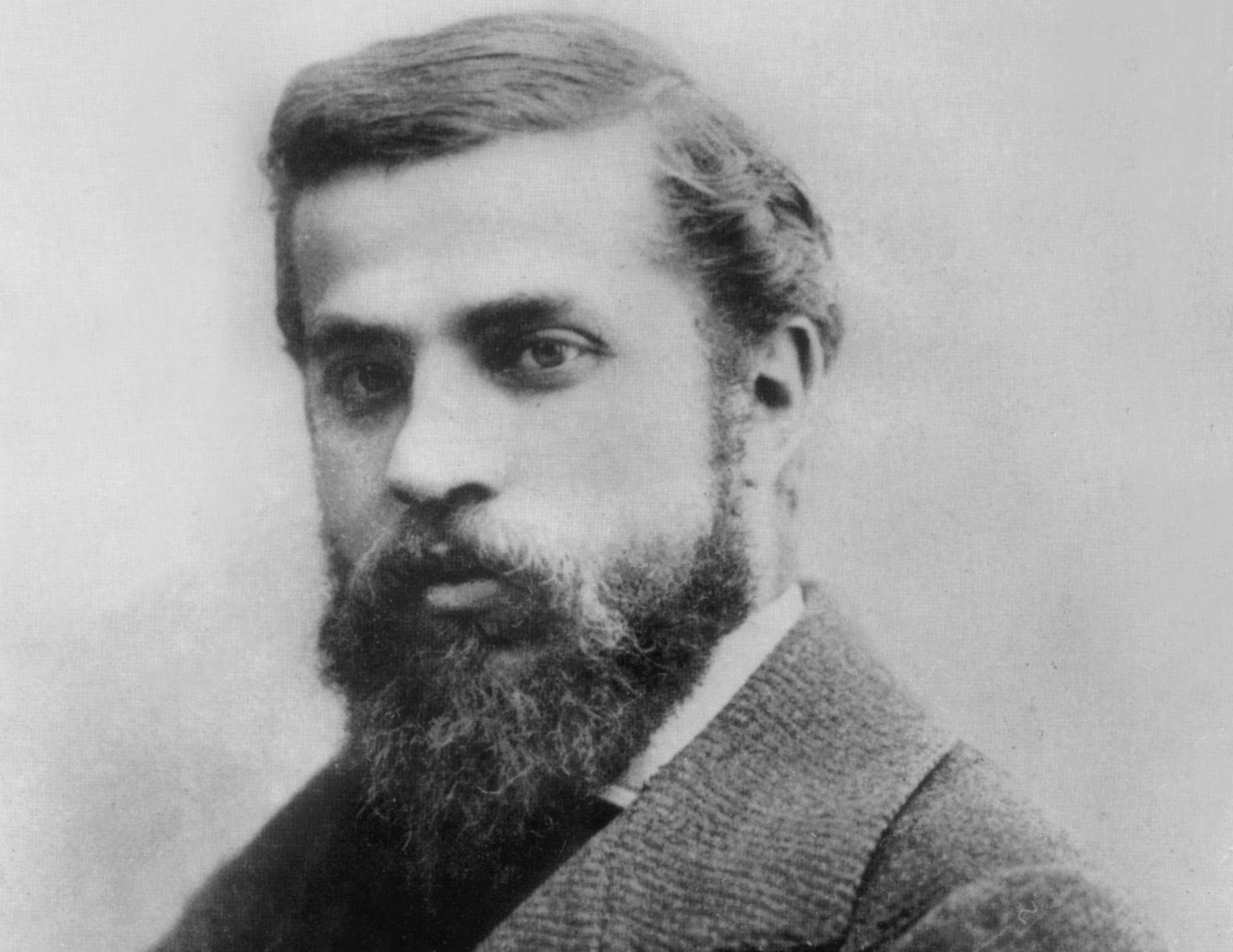

Antoni Gaudí circa 1882

APIC/GETTY IMAGES

But there was a difficulty — a difficulty that the British engineers tasked over a decade ago with finishing his vision have had to overcome. The foundations couldn’t handle it.

Gaudí was a visionary architect, but he was not the first architect of the project. He had taken over from a less visionary one, Francisco de Paula del Villar. In 1883, when Villar left the job, his church design was already under construction.

• I visited the Sagrada Familia tower — here’s what to expect

“There was nothing wrong with it,” said Tristram Carfrae, from Arup. “It was just a neo-Gothic church.” You could recognise it from a hundred similar churches. When Gaudí began though, on a new design you definitely could not recognise from a hundred similar churches, the crypt had already been started. It had not been started envisioning that it would be beneath 18 towers, the tallest 170m high.

The tower under construction

JOAN VALLS/URBANANDSPORT/NURPHOTO/GETTY IMAGES

JAMES BREEDEN FOR THE TIMES

“It didn’t have the foundations to support this monstrous tower,” Carfrae said.

So how would they make the tower directly over the crypt lighter? That was the question that he had to help answer 12 years ago when — with a cathedral still far from completion — the Sagrada Familia approached Arup. The call, he said, came “out of the blue”.

“It was unbelievable. It was one of those pinch-yourself moments. They didn’t even ask us to compete with anybody else, they just knocked on our door, saying, ‘Can you help?’” Carfrae said.

This was actually, by the standards of Sagrada Familia procurement, pretty rational. According to legend, Gaudí had himself been chosen because his future employer had had a dream in which the church was saved by a blue-eyed redhead.

• Barcelona plans Sagrada Familia ‘anteroom’ to ease selfie crowds

Gaudí hadn’t really ever built anything, but when the ginger architect turned up, he fitted the bill. “He was 30 years old. It was an extraordinary decision, really,” Carfrae said. “But he turned into one of the world’s greatest architects.”

When Carfrae sat down with the team to explore ways to lighten the tower, he hoped he would be an equally good choice.

Gaudí’s own design process is itself the stuff of architectural legend. To avoid using buttresses, he needed a way to cleanly transfer forces into the ground. What he opted for was the catenary arch — the shape made by a hanging chain.

To model a cathedral made of such arches, in a time before computer-aided design, he hung a lot of chains. Then, he added weights to represent the amount of stone. It worked like an analog computer. The whole cathedral was inverted — he modelled upside down in tension what would later be built the right way up in compression.

Jordi Fauli, the current chief architect, says that Gaudí’s models are not a sacred text though. Gaudí clearly assumed that new approaches would be developed. “He knew there were possibilities to build better. He knew new technologies would come along.”

Jordi Fauli

JAMES BREEDEN FOR THE TIMES

Work is still under way this month

JAMES BREEDEN FOR THE TIMES

Together, Arup and Fauli decided on a new approach. The original stone walls for the Sagrada Familia towers were 1.2m thick. They worked out that if they pre-squeezed them, inserting internal steel tendons under tension in a way that clamped the stones together to make panels, then they could still use stone, but get away with walls 30cm thick.

Today, piece by piece, the panels, which earned Carfrae the Royal Academy of Engineering’s Sir Frank Whittle Medal, have risen on the Barcelona skyline. This year, the tower grew higher than Ulm Minster, in Germany and became officially the highest church spire in the world. Next year, Carfrae and his colleagues will watch the cross be added to the top, and it will rival Montjuic — the hill that overlooks the city.

For Fauli, a Catholic, it is a tribute to God. “Here Gaudí wanted to communicate spiritual elevation with the elevation of the towers. It’s an expression of the Christian faith with architecture.”

Pieces of core of cross for tower of Jesus Christ being added

For Steve McKechnie, also part of the Arup team, it is something a little different as well. “It is not only a place of worship for God, it’s also just beautiful and astonishing, and it speaks somehow to the human spirit in a direct way. And, presumably, it will continue to make people feel awe and wonder and joy for centuries.”