Winter isn’t the ideal season for pruning trees in Upstate New York, but it’s the best time to cut scion or twigs from ash trees in parts of the state where the species has been all but wiped out.

Jonathan Rosenthal, co-director of the Ecological Research Institute’s Monitoring and Managing Ash program, calls these lone survivors “lingering ash,” and he believes they may provide the key to rescuing the species from impending extinction in North America.

“You can only collect the scion from them for grafting in the winter when the buds are entirely dormant,” Rosenthal said. “Otherwise, the grafting won’t work.”

Earlier this week, MaMA arborists cut branches from two lingering black ash trees in Hemlock-Canadice State Forest, in the heart of the Finger Lakes. The scion will be sent to Cornell Botanical Gardens where they’ll be grafted onto rootstock.

The hope is scientists will one day unlock the mechanisms that allow lingering ash trees to tolerate infestation from the emerald ash borer, an invasive beetle from East Asia that has killed hundreds of millions of ash trees in the U.S. over the past three decades.

“We want to find these trees and propagate them to keep that genetic material in the environment from winking out,” said Todd Bittner, director of natural areas for Cornell Botanic Gardens. “That’s our particular role in the program—we’re essentially a gene conservation bank.”

The collaboration between MaMA and Cornell is part of The Nature Conservancy’s Trees in Peril project, which seeks to restore ash trees on a landscape scale using EAB-resistant cultivars.

MaMA has so far identified more than 230 lingering ash trees. Most are from the Hudson Valley region, ground zero for the beetle’s invasion of the Northeast, according to Rosenthal. The program has collected scion from 71 of these trees for use in Cornell’s breeding program.

Bittner’s goal is to have 50 to 60 genotypes or trees from different parents of three ash species—white, black, and green—in the ground, along with five clones from each of those parents as back up.

MaMA delivered the first batch of lingering ash cuttings to Cornell two years ago. The grafted trees were grown in pots until they were anywhere from three to seven feet tall.

In October, Cornell transplanted the first set of saplings from pots to a conservation bank in a natural area owned by the university.

In five years, the saplings will be big enough to provide scion for a new generation of ash trees that can be sent to other researchers for EAB resistance testing.

All told, it will take 15 to 20 years, from collection to propagation to field experiments, before scientists can begin to produce ash trees that might be able to withstand EAB’s onslaught.

But the window for finding lingering ash trees is closing fast. Conservationists have only a year or two after EAB kills 95% of the ash trees in a particular area to collect scion from lingering ash. Right now, the Finger Lakes region is in that “sweet spot,” said Bittner.

“The ash are really seriously declining in this region,” Bittner said. “Many places are reaching this 95% threshold or they’re going to within a year or so. And we only have a couple years to find more lingering ash before those also succumb to the emerald ash borer.”

A lingering white ash tree in NY’s Hudson Valley, surrounded by dead ash trees. Scientists are racing to find lingering ash trees before emerald ash borers wipe them all out. Lingering ash trees hold the key to creating future strains of ash trees that are highly resistant to EAB.Radka WildovaA patchwork quilt of dead trees

A lingering white ash tree in NY’s Hudson Valley, surrounded by dead ash trees. Scientists are racing to find lingering ash trees before emerald ash borers wipe them all out. Lingering ash trees hold the key to creating future strains of ash trees that are highly resistant to EAB.Radka WildovaA patchwork quilt of dead trees

Native to East Asia, EAB was first found in the U.S. in Michigan in 2002, though experts believe it likely hitched a ride a decade earlier on wood shipping crates from overseas. EAB has since spread to 37 states.

New York recorded its first case of EAB in Cattaraugus County in 2009. By 2014, it had arrived in Central New York.

Today, EAB has been confirmed in every NY county except Hamilton and Lewis, according to the state Department of Environmental Conservation.

Left to their own devices, EAB spread slowly. Adult beetles fly less than a half-mile from their host trees. But people unwittingly transport EAB long distances by hauling infected firewood and nursery stock. The same year EAB came to NY, DEC banned moving untreated firewood more than 50 miles from its source.

Areas of NY most impacted by EAB infestation generally coincide with large population centers connected by major highways such as Buffalo, Rochester and Syracuse. But the bug’s spread hasn’t been uniform.

“A lot of people think EAB has already killed off all the ash everywhere,” Rosenthal said. “Actually, the distribution is like a patchwork quilt.”

For instance, in areas like the Catskills where EAB has been present for a long time and there’s very high ash mortality, it’s still possible to find places untouched by EAB.

Signs of EAB infestation:

“Blonding” of trunk from woodpeckers chipping off bark to find EAB larvae;Upper canopy dieback;D-shaped holes in bark;S-shaped tunnels under bark. In this triptych, a white ash tree located in Clark Reservation State Park shows evidence of damage from emerald ash borers, including S-shaped galleries in the cambium (left), and D-shaped exit holes in the bark (right). An EAB larva is shown in the middle photo.Mike ServissLast man standing

In this triptych, a white ash tree located in Clark Reservation State Park shows evidence of damage from emerald ash borers, including S-shaped galleries in the cambium (left), and D-shaped exit holes in the bark (right). An EAB larva is shown in the middle photo.Mike ServissLast man standing

Adult EAB burrow into ash trees and lay eggs in the cambium beneath the bark. EAB larvae then chew their way through the cambium for about two years, leaving behind telltale tunnels that cut off the flow of nutrients between the tree’s roots and upper canopy.

Most ash trees infested with EAB die within two to four years. Lingering ash are often surrounded by bare stands of dead and dying ash trees.

“They’re kind of like the last man standing,” Bittner said.

Lingering ash trees shouldn’t be confused with trees that sprout in the aftermath of an EAB invasion, or trees growing in areas with less than 95% ash mortality.

To qualify as a lingering ash, trees must be chemically untreated, measure at least four inches in diameter at breast height, and retain healthy crowns. Most importantly, lingering ash are found only in areas with at least 95% ash mortality.

Scientists believe there are at least two mechanisms that make lingering ash trees more resistant to EAB. For one, lingering ash can wall off EAB larvae early in their life cycle, trapping them in a layer of cambium where they starve to death.

Another hypothesis is that lingering ash trees emit a different chemical signature that makes it more difficult for adult EAB to find them—a kind of invisibility cloak.

But lingering ash trees are not completely immune to EAB. Even the hardiest specimens will eventually succumb to the EAB swarm. Finding the lone survivors is a race against time.

Emerald ash borer beetle shown next to a penny on a piece of an infested ash tree. Serpentine patterns on the bark are created by EAB larvae as they feed under the bark. Michael Mancuso | For NJ.com.TT TT Michael MancusoBlack ash a priority

Emerald ash borer beetle shown next to a penny on a piece of an infested ash tree. Serpentine patterns on the bark are created by EAB larvae as they feed under the bark. Michael Mancuso | For NJ.com.TT TT Michael MancusoBlack ash a priority

Conservationists want lingering ash from as many different areas as possible to maintain regional genetic diversity and to provide an insurance policy against future blights that might otherwise wipe out trees of a single cultivar or genotype.

“We want lingering ash source trees from New York to be planted in New York, and we want Ohio trees to be planted in Ohio,” he said, “partly because they were adapted to those local conditions, those local soils, those local climates.”

A high priority is given to black ash trees, which are far less common than white and green ash and “die much more quickly than the other two species when they’re attacked by EAB,” Rosenthal said.

Black ash typically grow in swampy areas and are critical in regulating complex wetland hydrology. Once EAB kills off all the black ash in a wetland, water levels rise and what was once a swamp can become a pond or a lake.

Furthermore, black ash hold great cultural significance for many Native American communities.

“They’re used primarily for basketry and also for ceremonial purposes,” Rosenthal said, “and even feature very importantly in their language and so forth. So it’s really crucial for them that black ash be conserved.”

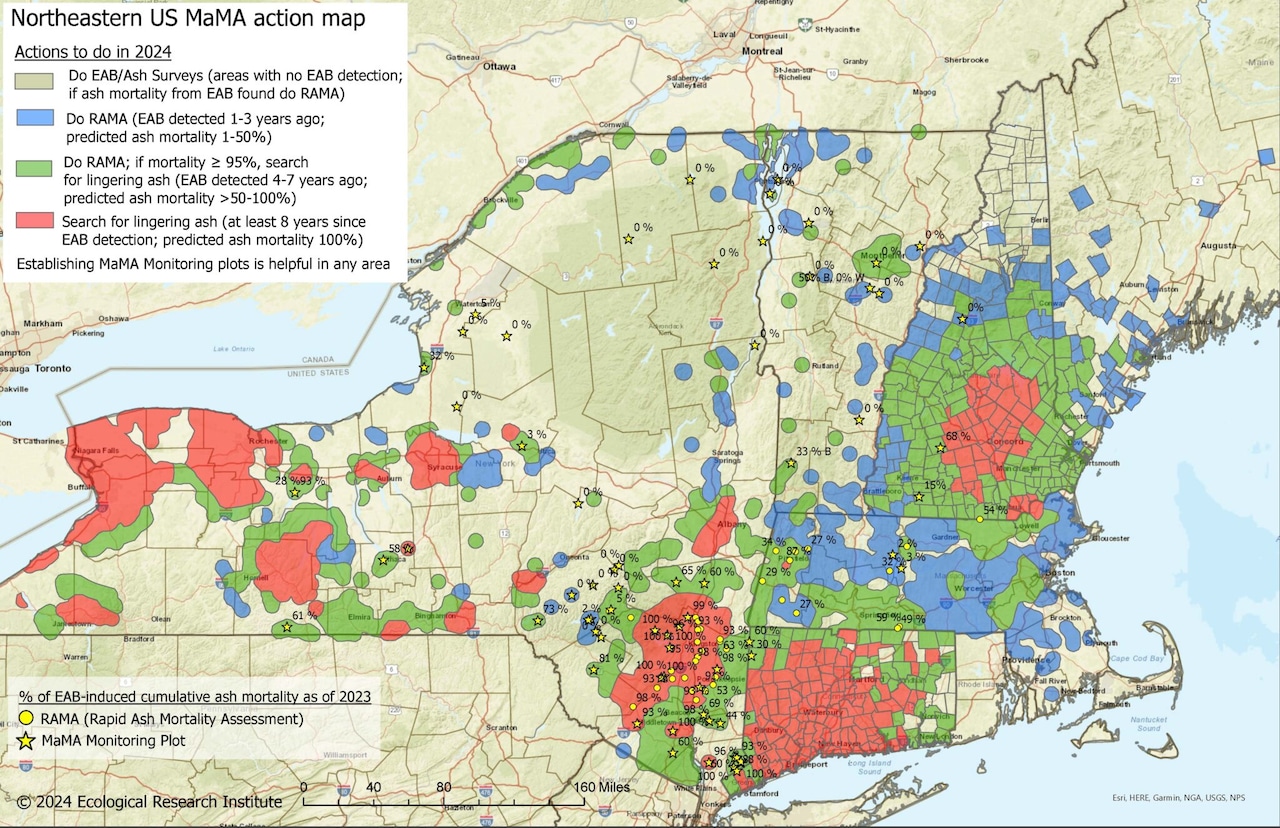

This map from the Monitoring and Managing Ash project shows levels of ash tree mortality due to EAB infestation in areas across the Northeast. Lingering ash trees are found in areas with at least 95% mortality (red or green on the map).MaMACitizen science

This map from the Monitoring and Managing Ash project shows levels of ash tree mortality due to EAB infestation in areas across the Northeast. Lingering ash trees are found in areas with at least 95% mortality (red or green on the map).MaMACitizen science

For a long time, EAB seemed unstoppable. The fate of ash trees appeared to be going the way of the American chestnut, a majestic tree that once dominated the landscape east of the Mississippi River. But the discovery of lingering ash changed all that.

“People were hopeless. And when they’re hopeless, they don’t do anything,” Rosenthal said. “But when we started finding lingering trees, people were like, ‘Oh, they’re real!’ It’s a game changer because it gives people hope, and if they have hope, they take action.”

Here are two ways you can take action to help save ash trees from annihilation. All you need is smartphone and a little bit of naturalist training.

Cornell Botanical Gardens recommends using the TreeSnap app to document locations of lingering ash using your smartphone. With a tap of your finger you can virtually tag trees in the wild on a digital map for follow up by scientists.

MaMA also has a similar smartphone app you can download from Anecdata.org. There are various levels of participation, from virtual tagging of individual EAB infected trees, to more complex evaluations of EAB infested areas.

MaMA’s Rapid Ash Mortality Assessment protocol is somewhat more involved than tapping your smartphone. It requires you to assess the health of 40 mature ash trees, dead or alive, in a chosen area to help scientists determine when and where to search for lingering ash.

The protocol is especially helpful in areas where EAB infestation is documented but tree health data are lacking. You need to be able to identify ash trees, assess their crown health, recognize evidence of EAB, and estimate tree diameter.

For more information, including training materials, visit MaMA’s website.