When the King visited Greenland in April—looking jaunty and at ease while cruising on a fjord with the Prime Minister, and taking a coffee-and-cake break with locals at a cultural center in Nuuk—the contrast with Vance’s gloomy trip couldn’t have been starker. Shortly before the royal visit, the King had issued an updated coat of arms for the Kingdom of Denmark in which the symbols for Greenland and the Faroe Islands, the other Danish territory, take up more space. In the new flag, it’s easier to see that Greenland’s polar bear is roaring.

Denmark recently pledged to give Greenlanders an additional quarter of a billion dollars in health-care and infrastructure investments. Trump’s nakedly imperialistic rhetoric has also prompted Danish leaders to look more honestly at their own role as a colonial power. In August, for example, Frederiksen issued an official apology for a program, started in the nineteen-sixties and continued for decades, in which Danish doctors fitted thousands of Indigenous Greenlandic women and girls with intrauterine birth-control devices, often without their consent or full knowledge.

Such reckonings are overdue. In 2021, Anne Kirstine Hermann, a Danish journalist, published a pioneering book, “Children of the Empire,” in which she chronicled how little say Greenlanders had in Denmark’s decision to incorporate the former colony into its kingdom, rather than granting it independence. Hermann told me, “Danes aren’t used to being the villain—we’re do-gooders. But Greenland has a whole different experience.”

Pernille Benjaminsen, a human-rights lawyer in Nuuk, said that Danes have always compared themselves, favorably, “to what happened in North America—putting Indigenous people in reservations, killing them.” But, she noted, “a lot of bad things also happened in Greenland—we had segregation between white Danish and Greenlandic people, we had eras when we were asked to leave stores when Danish people wanted to enter.” She added, “We need to kill the narrative that there can be a ‘good’ colonizer.”

Benjaminsen credited Prime Minister Frederiksen for being more forthright about the colonial past. Around the time that Trump returned to office, Frederiksen posted online that Danes and Greenlanders “have some dark chapters in our history together, which we, from the Danish side, must confront.”

Some people in Copenhagen told me that, for younger Danes, the Black Lives Matter movement in the U.S. had spurred soul-searching about their own country’s racism toward Inuit Greenlanders. But Denmark’s sudden attentiveness to Greenland was also an inadvertent gift from Trump. Hørlyck, the photographer, told me, “He has activated Danish people’s connection to Greenland.” Danes of his generation were asking themselves, in a way they hadn’t before, “What do I really know about Greenland? Have I really talked to Greenlanders?” He went on, “It’s quite funny that the strategy over there from Trump opens up something positive here.”

Trump’s antagonism toward Greenland has also changed Danish views about European unity. In the past, Danes had been soft Euroskeptics. They joined the E.U. in the nineteen-seventies, but they kept their own currency, the krone, and in 1992 they voted against the Maastricht Treaty, which tightened European conformity regarding security, citizenship, and other matters. When Frederiksen recently called for more defense spending, she acknowledged, “European coöperation has never really been a favorite of many Danes.” They’d grumbled, she said, about everything from “crooked cucumbers and banning plastic straws” to open immigration policies, which Frederiksen’s government had rejected.

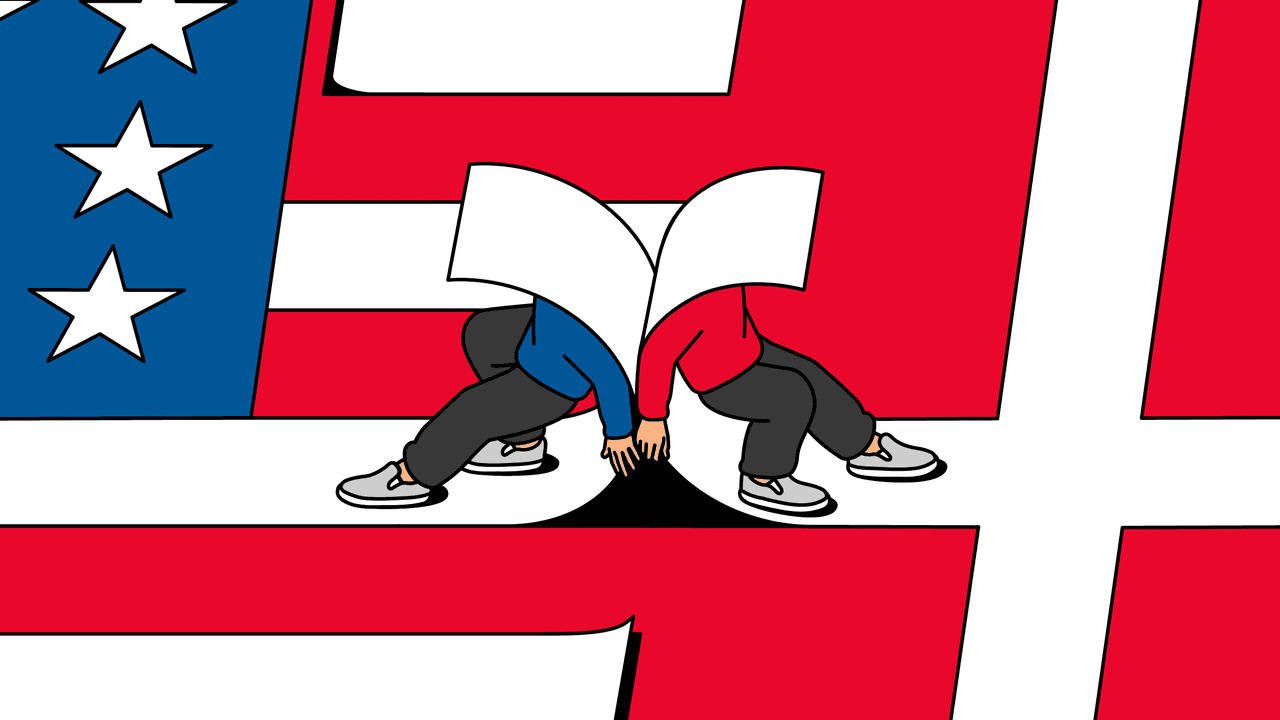

Ole Wæver, a professor of international relations at the University of Copenhagen, told me that Danes have long had a “kind of anti-E.U. sentiment, with a lot of the same arguments that you saw in Brexit—‘Oh, it’s big bureaucracy,’ ‘Brussels is far away,’ ‘It’s taking away our democracy.’ ” Such attitudes, Wæver said, had helped to make Denmark “go overboard” in its allegiance to America. Elisabet Svane, a columnist for Politiken, told me, “Our Prime Minister used to say, ‘You cannot put a piece of paper between me and the U.S., I’m so transatlantic.’ She’s still transatlantic, but I think you can put a little book in between now.”