A common parasite known for silently embedding itself in the brain has revealed a new survival strategy: hijacking the very immune cells meant to destroy it. But scientists at UVA Health have found that an enzyme inside those cells (caspase-8) can shut the infection down by triggering the cell’s own death.

This research sheds light on how the body protects itself from Toxoplasma gondii, a parasite estimated to infect nearly a third of the global population. While it rarely causes symptoms in healthy individuals, it can become deadly for those with compromised immune systems. The new findings explain why some immune responses fail and how the body keeps this chronic invader under control.

T. gondii typically enters the body through contaminated food or cat exposure, spreading through tissues before establishing a lasting presence in the brain. The University of Virginia research team, led by Dr. Tajie Harris, discovered that the parasite is capable of infecting CD8+ T cells, which are usually tasked with destroying infected cells. Understanding how these cells resist infection, or fail to, has implications for treating at-risk patients.

Immune Cells Are Not Immune to the Parasite

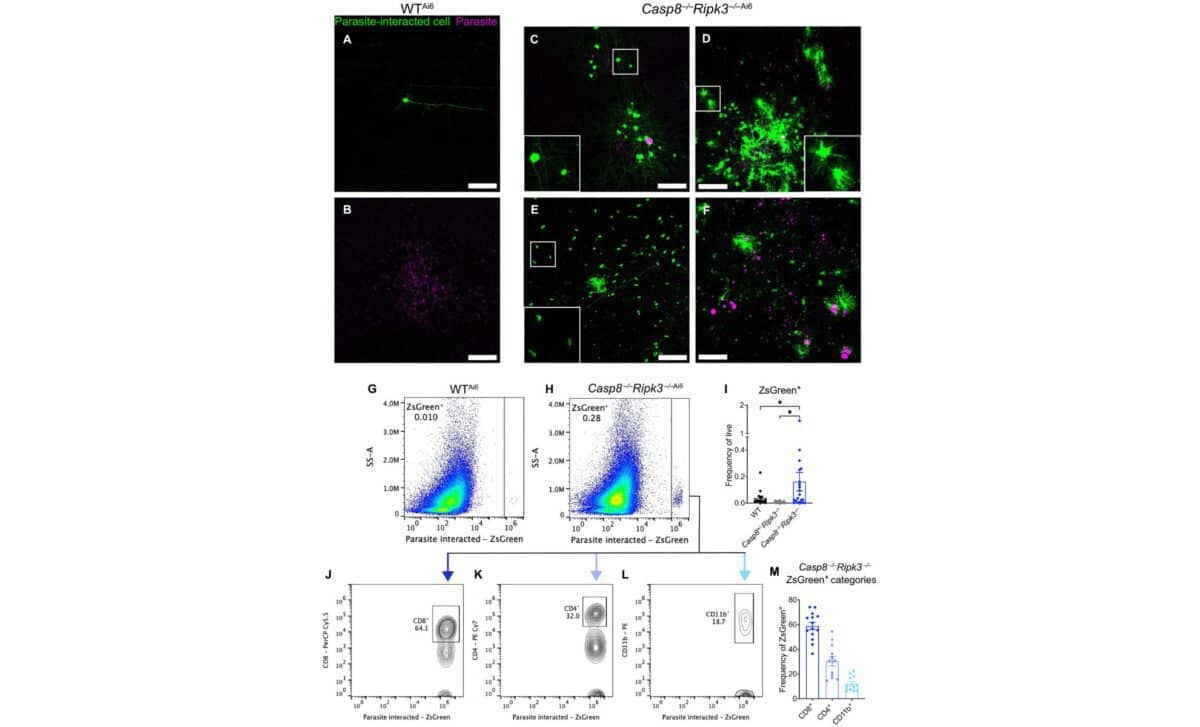

Dr. Harris’s team observed a surprising behavior: CD8+ T cells, normally the body’s first line of defense against infected cells, could themselves become infected by T. gondii. According to the research published in Science Advances, infected T cells in mice without caspase-8 allowed the parasite to replicate and spread.

“We found that these very T cells can get infected, and, if they do, they can opt to die,” Harris explained in a UVA Health report. That self-destruction, initiated by caspase-8, prevents the parasite from completing its life cycle, effectively cutting off its survival route.

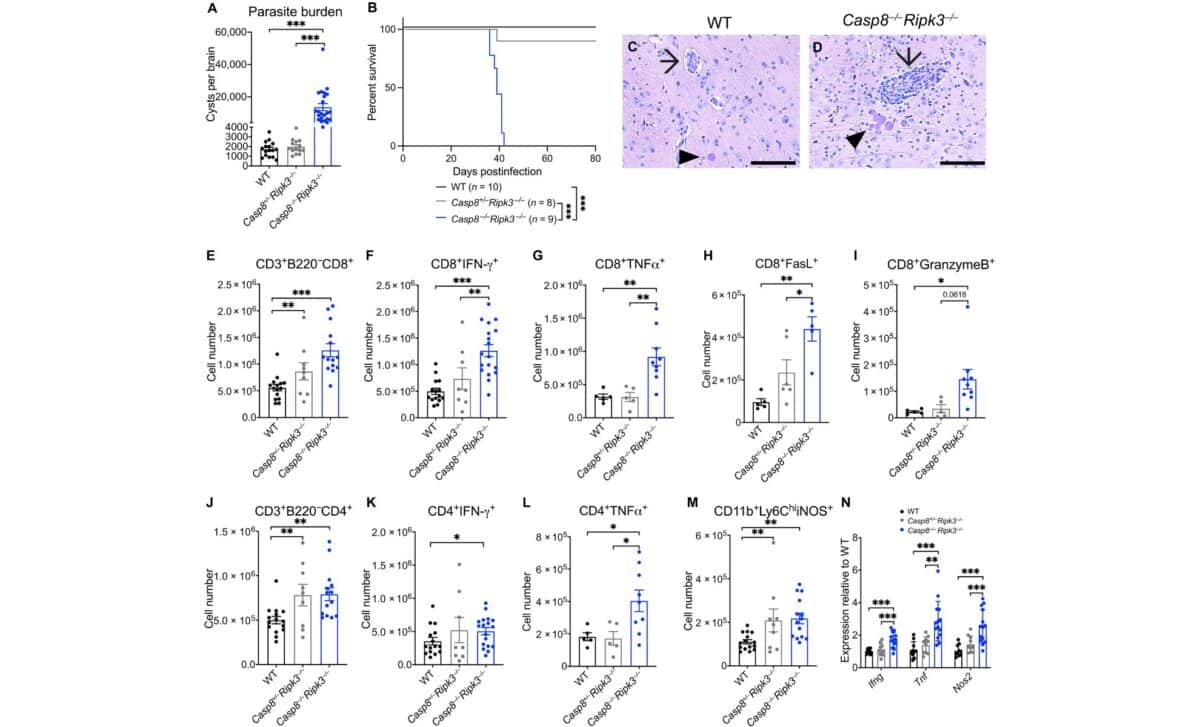

In mice lacking caspase-8, the parasite’s presence in the brain soared. Despite generating a strong immune response, those mice became seriously ill and died, their brains filled with infected T cells. By contrast, mice with functioning caspase-8 survived, their immune cells clearing the infection effectively.

The Role of Caspase-8 in Brain Defense

The enzyme caspase-8 is best known for initiating apoptosis, a self-destruct program within cells. But its role in immune defense, especially in the brain, has only recently come into focus. According to UVA researchers, mice engineered to lack this enzyme showed an eightfold increase in brain parasite load compared to their normal counterparts.

The study used advanced genetic models, including mice with CD8+ T cell-specific deletions of caspase-8, to track how the parasite interacts with different cell types. Infected T cells from these models carried multiple parasites, sometimes even hosting clusters of replicating organisms inside a single immune cell.

Despite high levels of immune signaling molecules like interferon-gamma and TNF-alpha, the absence of caspase-8 allowed the infection to persist and worsen. This highlighted the enzyme’s importance not just for initiating cell death, but for actively limiting the spread of pathogens inside the immune system’s own ranks.

Only One Cell Type Relies on This Suicide Switch

Although T. gondii was found in other brain cells (neurons, astrocytes, and microglia) the loss of caspase-8 in those cell types didn’t significantly change parasite levels or affect disease progression. The key vulnerability lay specifically within the CD8+ T cells, according to the researchers.

To further confirm this, the team tested mice with targeted deletion of Fas, a death receptor known to activate caspase-8. These Fas-deficient mice also developed high parasite loads and died sooner than normal mice, underscoring the pathway’s role in parasite control.

The study, funded by multiple NIH grants and supported by the University of Virginia’s BIG Center, suggests that T. gondii might be exploiting a narrow window in the immune response: when T cells are infected but haven’t yet triggered caspase-8. “The only pathogens that can live in CD8+ T cells have developed ways to mess with caspase-8 function,” Harris noted.

The discovery that a parasite can turn the immune system against itself, and that a single enzyme can turn the tide, opens new questions about how other infections might exploit similar pathways. For now, this research marks a major step in decoding how the brain fights one of its most stealthy intruders.