Israeli scientists have developed an innovative method to track the human body’s circadian rhythms, finding in a new peer-reviewed study that female sex hormones have a dramatic effect on the setting of these internal circadian clocks.

Every human body has a central circadian clock in the brain that helps control its daily rhythms — but there are also circadian clocks within almost every cell in the body that follow their own tick-tocking beat.

The researchers mapped circadian clocks across many cells using their method, called CircaSCOPE, to find that these female sex hormones — especially progesterone — along with the stress hormone cortisol, have a dramatic effect on the setting of these internal timers.

When these clocks are not coordinated, people can experience serious health problems, including sleep disorders, diabetes and cancer.

The body “needs to synchronize millions of clocks because they are present in every cell in our body,” said Prof. Gad Asher of the Weizmann Institute of Science’s Asher lab, recently speaking to The Times of Israel.

Get The Times of Israel’s Daily Edition

by email and never miss our top stories

By signing up, you agree to the terms

“Sex hormones are very important in shifting the clock,” Asher said. “Female hormones have a much more prominent effect compared to male hormones.”

He said that the researchers still “don’t know how this influences men.”

Asher noted that the experiments were done in cell cultures and have not yet been tested in animals or humans.

However, he said, “We now know how these clocks communicate, so maybe we can explain their involvement in various disorders and pathologies, and help patients whose internal timing is disrupted.”

The research could also shed light on disruptions to circadian clocks during menstruation, pregnancy and menopause.

The study, led by Dr. Gal Manella, Dr. Saar Ezagouri, and Nityanand Bolshette, was published in the scientific journal Nature Communications.

From left to right, Dr. Gad Asher, Dr. Nityanand Bolshette, Dr. Gal Manella, and Dr. Saar Ezarouri of the Weizmann Institute of Science’s Asher Lab. (Courtesy)

Our internal clocks sometimes beat to different times

In the past, Asher said, “people thought that there is only one main clock in the brain which responds to light and dark and coordinates our daily physiology, metabolism, and behavior.”

Then, about 25 years ago, scientists discovered that there are “clocks in every cell, in every tissue” in the body.

Circadian clocks are affected not only by external signals such as sunlight but also by signals carried through the bloodstream.

When the body’s internal time is not aligned with the environment, it could lead to many pathologies, Asher said.

“The best example is jet lag or shift workers, in which the person’s internal time is not in accordance with the environmental time,” he explained.

“The brain receives information from the eyes about light and darkness,” Asher said. “Light and dark are the main time signals for the brain. But now, in the past year, it’s becoming more and more evident that illnesses might be related to the fact that clocks in different organs are not synchronized with each other.”

For example, he said, “The clock in the liver should be synchronized, or should show a similar time as the clock in the kidney or the clock in the brain, but this is not always the case.”

Prof. Gad Asher of the Weizmann Institute of Science’s Asher Lab notes measurements in an experiment on how low oxygen affects the body’s circadian clocks in La Rinconada, Peru, the highest permanent settlement in the world, in 2020. (Courtesy/Asher Lab)

Low oxygen levels impact circadian rhythms

In a series of studies on animal models, researchers in Asher’s lab showed that oxygen acts like a signal helping internal clocks know what time it is. When oxygen levels change, cells use that information to adjust internal clocks.

In 2020, Asher joined an expedition to La Rinconada, Peru, the highest inhabited settlement in the world, located 5,300 meters (17,388 feet) above sea level.

At this high altitude, Asher said the lower levels of oxygen altered the daily rhythm of many genes.

“These findings might be of relevance to the fact that many low oxygen-related pathologies, such as heart disease and asthma exacerbation, show daytime occurrence, in particular during the early morning hours,” Asher said.

A view of La Rinconada, Puno, Peru. (E. Michael James/iStock)

A wall of clocks

There are other signals carried through the blood that might serve as time tellers for internal clocks, Asher said, “yet their identity was only partially known.”

Before Asher’s work, these blood-borne signals had not been fully mapped because researchers lacked a precise and efficient method for tracking the clock’s response to different signals over a full 24-hour cycle.

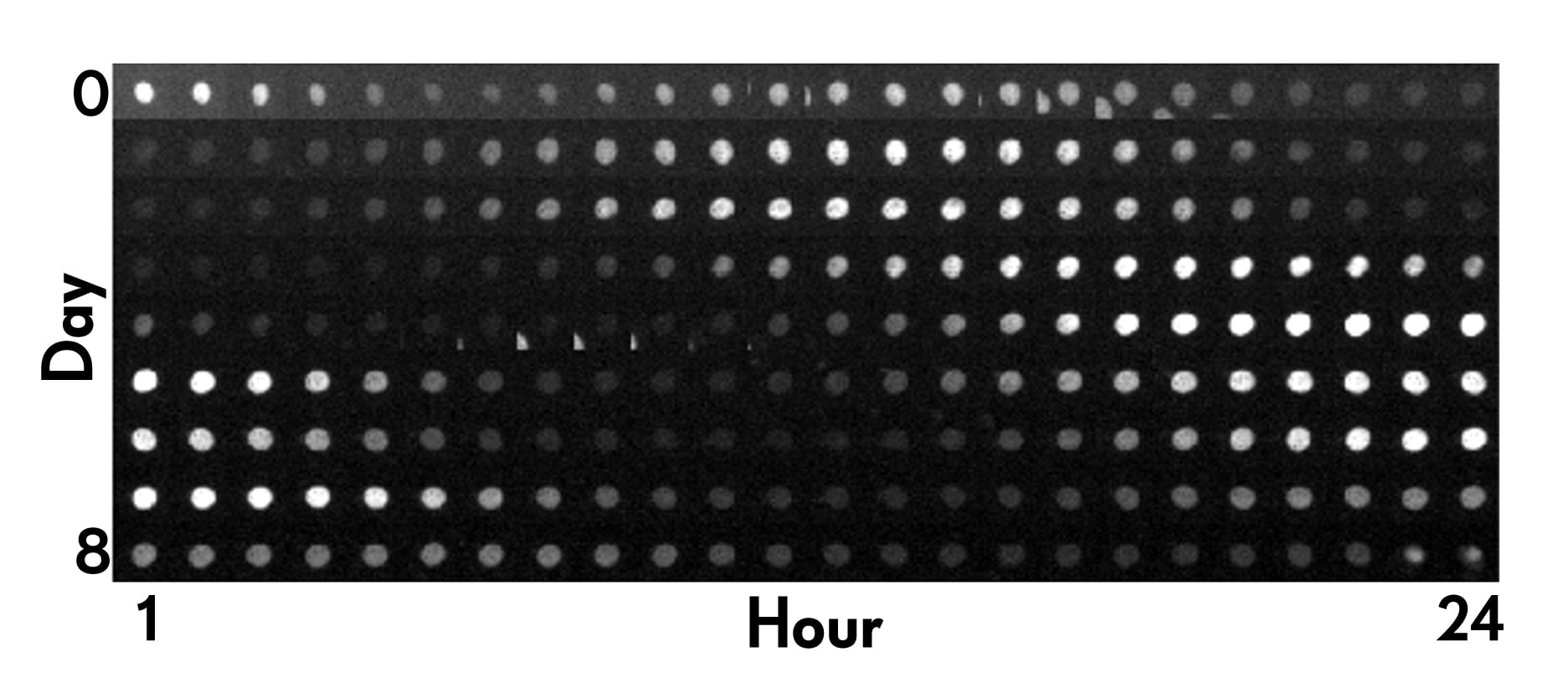

The Weizmann scientists’ CircaSCOPE uses an array of human cells, each representing a different time of day, resembling a wall lined with clocks showing the current time in major cities around the world.

Asher’s lab was not damaged during the Iranian ballistic missile strike in June 2025, though he noted that some of the experiments used for the research paper were delayed.

Nevertheless, the researchers were able to monitor the clock in every cell in a petri dish in the culture. When they exposed the cell to a signal, they could “characterize if the clock was moving forward, backward, or not responding,” Asher said.

In the past, it would have taken the researchers months to do this work. He said that the novel method enables them to screen for dozens of compounds within a single week.

“If we suspect that a certain compound affects the clock, we add it to the cells, and we can see exactly where their clocks are moving in each cell,” said Asher. “This is a very powerful approach which can generate a lot of information about how the clock is responsive to different signals.”

The ‘ticking of a circadian clock inside a human cell over the course of 24 hours. A fluorescent marker allows scientists to tell ‘what time it is’ at any given moment. (Courtesy)

The importance of the Cry2 protein

In addition to uncovering the influence of sex hormones, Asher’s study revealed that the clock component receiving these signals in the blood is the protein CRY2 (Cryptochrome 2), rather than PER2 (Period 2), as previously believed.

“It seems that the sex hormones, as well as many other signals, are acting through the CRY2 protein,” he said. “It probably transfers the information into the clock in the cell.”

“From an evolutionary angle, that’s intriguing,” said Prof. Yoav Gothilf of Tel Aviv University’s School of Biochemistry, Neurobiology and Biophysics, whose lab explores various aspects of the circadian clock and its significance in the life of the organism.

Gothilf, who was not involved in the study, explained that in early, simple organisms, CRY2-like proteins responded directly to light, acting like a light sensor. As animals became more complex, CRY2 kept its job of synchronizing internal clocks, but the signal it listened to changed.

“It seems the role of CRY2 in synchronizing clocks has been conserved, but the signal it responds to has changed, from light in early life forms to hormones in mammals,” Gothilf said.

Gothilf said that Asher’s study suggests that “daily, age-specific waves of hormones can shift the timing of our internal clocks.”

The findings offer a “compelling” biological explanation for “how a morning-loving child will turn into a night-owl teenager, and later drift back toward morningness as an adult.”

Asher said that his lab will continue to research the roles of these hormones in circadian clocks, perhaps testing the idea on lab animals.

“We can now identify compounds, and we identify that the sex hormones are important, changing throughout life,” he said. “Identifying molecules that are potent time signals for clocks has major importance in treatments in the future.