The distribution of fragments of a shattering object becomes predictable

Fragmentation has long been of interest to scientists, as it can be used to better understand what happens during earthquakes or rockfalls, electron bombardment or nanoparticle production. These phenomena are essential for industry, astrophysics and geophysics.

However, predicting how a vase, a rock or a soap bubble will break seems extremely complex: indeed, it’s hard to imagine that these different elements can fragment according to a common law.

What’s more, the number of fragments, their shape and size, could be a bit of a Fields Medal puzzle, awarded every four years for the world’s best mathematical contribution.

But that’s what Emmanuel Villermaux, a French physicist from the University of Aix-Marseille, proposed in a paper published in Physical Review Letters on November 25, 2025 (1).

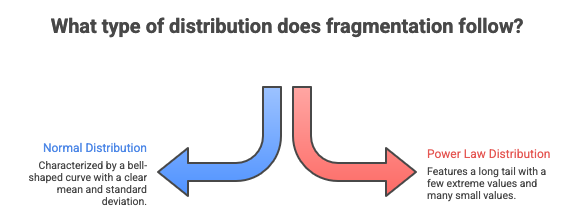

Instead of looking at the different causes of fragmentation, particularly in terms of the materials involved, he decided to study the result of these divisions in terms of distribution and shape. He discovered that this result respects a power law and not a normal law.

If we study the distribution of human height, the majority are between 1m60 and 1m90. You’re unlikely to meet a man measuring 20 meters or 2 centimeters. Human height thus follows a normal distribution with a calculable mean.

In the case of a power law, the opposite is true. The distribution of wealth on our planet follows a power law: a few billionaires own as much as billions of poor people.

This means that if we measure the size of the debris produced by a rock explosion in a mine, we won’t get a majority of average “pebbles”, which would respect a normal law, but the result will respect a power law: millions of grains of dust, thousands of small gravels, and a few rare huge boulders.

Incredibly, the study showed that this power law remains valid whatever the material involved, be it solid or liquid. It’s as if the Universe had a universal recipe for fragmentation.

“The simplicity and success of this approach are remarkable. The results suggest that the statistical characteristics of fragmentation are dictated not by the microscopic details of cracks or instabilities, but by the way in which randomness is constrained by global kinematics.” (2)

The only exception is in the case of certain plastics or a continuous, random-free fluid, such as water flowing from a tap.

Earlier work had followed Plato’s intuition as to the shape of fragments: nature produces cubes in preference.

In ancient times, the philosopher Plato believed that the universe was made up of atoms with perfect geometric shapes. For him, the element “Earth” was made up of cubes, as the most efficient way of filling space. A team of Hungarian and American researchers wanted to check whether, mathematically and physically, nature actually “preferred” cubes when breaking objects. (3).

The researchers studied thousands of fragments: rocks broken by erosion, tectonic plates, even cracks in dried mud.

Their conclusion is striking: if you take any solid object and break it randomly into a large number of pieces, the average shape of these pieces is a cube. This doesn’t mean that every pebble is a perfect cube; pebbles are clearly irregular. This means that if you count the number of faces, vertices and edges of all the pieces, the geometric average corresponds exactly to that of a cube (6 faces, 8 vertices).

The same applies to a small stone or a continent. Why cubes and not pyramids or spheres? Researchers have shown that when cracks propagate in a material, they tend to intersect at right angles. In three dimensions, these intersecting cracks end up cutting space into brick-like blocks. This is the most “natural” and probable way for matter to divide.

The Villermaux equation applied to the social sciences?

Emmanuel Villermaux’s proposal, backed up by previous work on fragmentation, opens up real prospects for better analyzing, predicting and evaluating all phenomena linked to the fracturing of an element, whether solid or liquid; earthquakes, tsunamis, supernova studies, prediction of structural modifications at atomic level linked to pressure, temperature or shocks.

The applications are numerous, and future developments could form the basis of a global theory of fragmentation. And we’re beginning to dream that this theory could be applied to the social sciences, in the same way as systemics – originally a mathematical discipline – to predict, analyze and evaluate societal fragmentation.

Illustration: ShutersStock – 2663820841

References

1- Fragmentation: Principles versus Mechanisms- Emmanuel Villermaux- Nov 2025- https://physics.aps.org/featured-article-pdf/10.1103/r7xz-5d9c

2- Decoding the chaos of rupture – Physics- Ferenc Kun- Nov 26, 2025- https://physics.aps.org/articles/v18/184

3- G. Domokos et al, “Plato’s cube and the natural geometry of fragmentation” – July 17, 2020- https://www.pnas.org/doi/full/10.1073/pnas.2001037117

4- Can we get out of a black hole? Thot Cursus – November 21, 2018- https://cursus.edu/fr/15678/peut-on-sortir-dun-trou-noir

5- Predicting the unpredictable: now within our grasp – March 9, 2020 – Denys Lamontagne – https://cursus.edu/fr/21453/predire-limprevisible-maintenant-a-notre-portee