The European Space Agency (ESA) is preparing for one of its most ambitious scientific adventures yet, the Comet Interceptor mission, designed to intercept and study a pristine comet or possibly an interstellar object visiting our solar system for the first time. The mission, set to launch earlier than expected, aims to capture a glimpse of primordial material untouched since the dawn of the Solar System.

A New Opportunity For Discovery

Originally slated for a later date, the Comet Interceptor mission has now moved up its launch window due to a delay in another ESA program, according to Space News. This reshuffle provides an unexpected advantage: a more capable Ariane 62 launch vehicle and an earlier start for one of ESA’s most intriguing scientific projects.

ESA confirmed that the spacecraft will now head to space in 2029 from Europe’s Spaceport in French Guiana. Once in orbit, the main spacecraft will be “parked” at the L2 Lagrange point, where it will wait for the perfect target, a comet entering the inner solar system for the very first time.

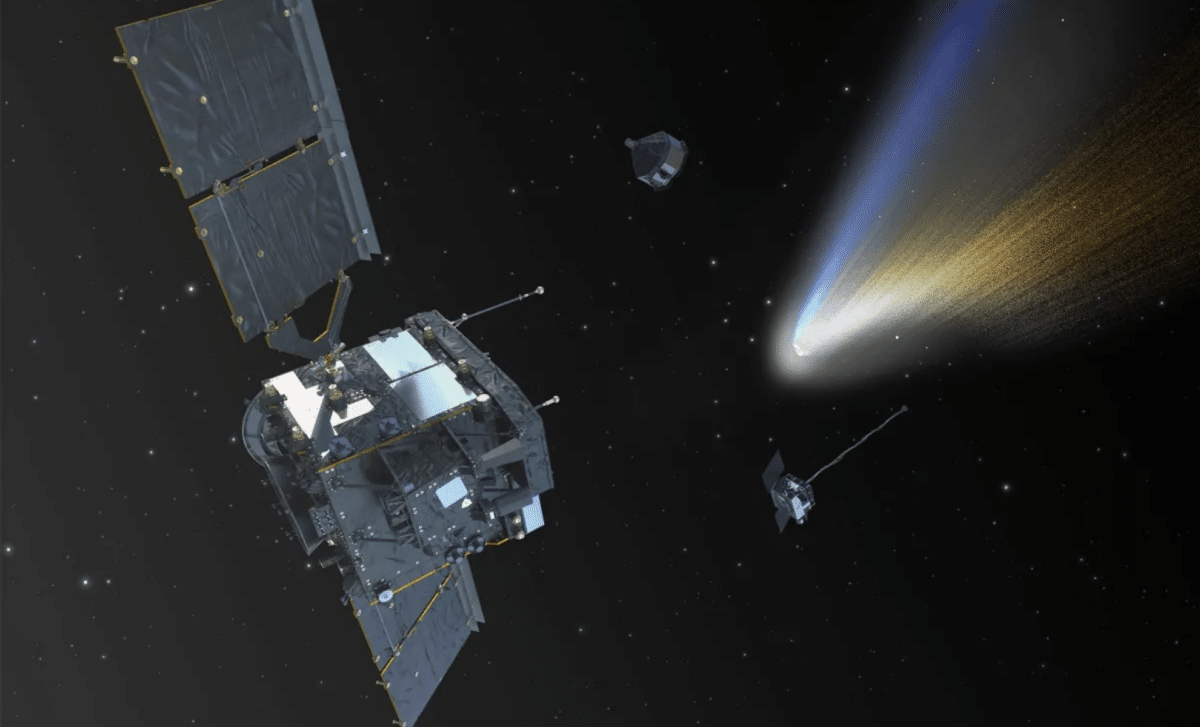

When the ideal target is identified, the spacecraft will maneuver into an intercept trajectory. Upon approach, it will release two small probes, designed to capture high-resolution, multi-angle observations of the comet’s nucleus, gas, and dust environment. This dynamic approach will allow scientists to build a 3D profile of a cosmic object that has never interacted with the Sun.

ESA’s Comet Interceptor mission moves up launch https://t.co/vOycGPn6bV pic.twitter.com/9zTFvCzR1o

— SpaceNews (@SpaceNews_Inc) January 14, 2026

The Science Behind Comet Interceptor

The Comet Interceptor mission is a collaboration between ESA and the Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency (JAXA). Together, they aim to unlock secrets about the raw materials that formed planets and life billions of years ago.

Comets are often called time capsules, carrying unaltered material from the formation of the Solar System. Most comets we’ve studied have been shaped by repeated passes near the Sun, altering their composition. But Comet Interceptor’s goal is to meet a truly pristine comet, one that’s been wandering in the cold outer regions since the Solar System’s birth.

According to ESA, the mission will employ ten scientific instruments across its three spacecraft to analyze the comet’s composition, plasma environment, and dust. The coordinated data will help researchers understand how volatile materials, such as water and organic molecules, were distributed throughout the early Solar System and possibly delivered to Earth.

Building On Past Missions

The Comet Interceptor project stands on the shoulders of legendary missions like Giotto, which encountered Halley’s Comet in 1986, and Rosetta, which orbited Comet 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko between 2014 and 2016. Those missions revolutionized comet science, but both studied objects that had already been altered by their journeys near the Sun.

This time, scientists want to go further, literally and figuratively. By studying a comet from the farthest, most untouched regions of the Solar System, Comet Interceptor could provide new insight into how comets form, evolve, and interact with the interstellar medium.

As ESA notes, this mission is not just about exploration, but about patience and precision. The spacecraft will wait in a stable orbit until astronomers spot the right candidate, possibly a visitor from the Oort Cloud or even from another star system.

An Engineering Challenge With A Visionary Goal

Designing a spacecraft that can “wait” for years and then suddenly chase down a fast-moving comet is no small feat. The engineering challenges are immense. The probes must remain functional after extended dormancy, withstand deep-space conditions, and operate autonomously once released.

The mission will feature a main spacecraft and two smaller ones, Probe A and Probe B, the latter built by JAXA. Together, they will collect complementary datasets from different angles. The coordination between all three craft will create a detailed and comprehensive view of the target’s physical and chemical nature.

ESA engineers recently confirmed that the spacecraft’s structure passed rigorous vibration tests, ensuring it can survive launch stresses. The team’s next steps include completing system integration and verifying that the instruments can communicate seamlessly once deployed.