CLEVELAND, Ohio — Today dispatchers ask 911 callers if they need police, fire or EMS. But after a legislative compromise, Cleveland is one step closer to adding a fourth option: mental health professionals.

After a year of delay, Cleveland City Council and Mayor Justin Bibb have agreed to changes to move forward Tanisha’s Law, legislation that requires the city to send clinicians instead of police officers to certain mental health emergencies.

It is expected to go to a vote at city council’s next meeting on Jan. 26 and appears to have enough support to pass.

Councilwoman Stephanie Howse-Jones, one of the law’s sponsors, said there’s more to do to make the plan a reality, but said the legislation moving forward is something to celebrate.

“Now the city of Cleveland is taking the necessary steps to make sure people get compassionate and appropriate care,” Howse-Jones said.

Tanisha’s Law creates what proponents call a “care” response, where a mental health professional is sent in response to certain 911 calls involving mental health episodes, instead of police officers.

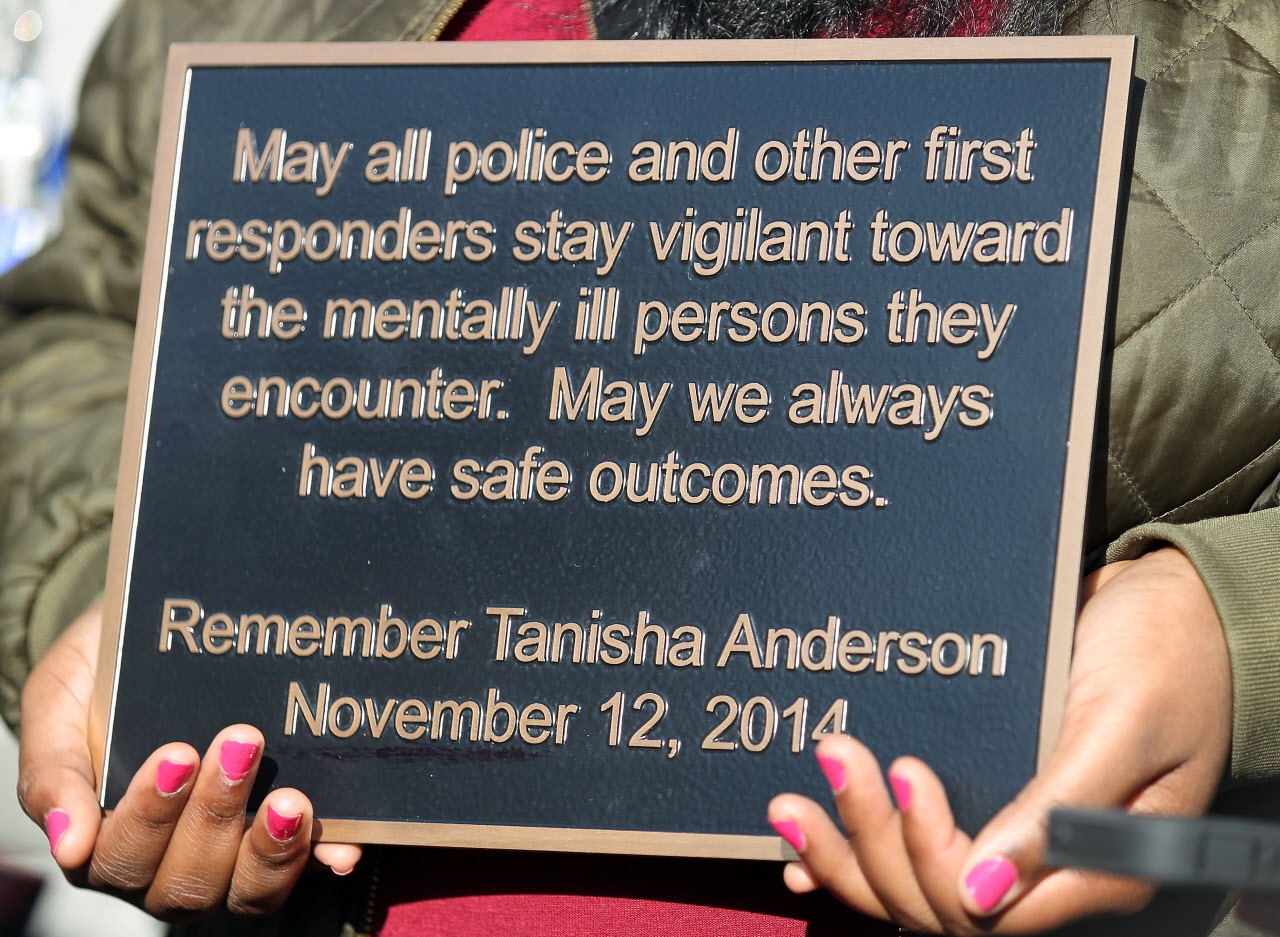

The legislation is named for Tanisha Anderson, whose family called 911 in November 2014 for help while she was experiencing a mental health episode. The Cleveland police officers who responded ended up arresting Anderson after she panicked and restrained her by kneeling on top of her for several minutes. Anderson died in part due to the asphyxia caused by the physical restraint. The officers were not prosecuted, and the city paid $2.25 million to settle a lawsuit filed by Anderson’s family.

Today, the Cleveland Division of Police doesn’t offer any care response, or mental health professionals who respond to 911 calls alone.

Officers do have “crisis” response, where police officers with crisis intervention training respond to 911 calls with skills needed to de-escalate a situation.

There’s also “co-response” where an officer responds paired with a mental health professional. Cleveland police have seven of these co-response teams and they mostly do follow-up visits but can also respond to live 911 calls.

The broader idea behind the legislation is that residents like Anderson would be better served by clinicians when undergoing mental health emergencies. Proponents say this also frees up police officers to spend more time responding to and investigating crime.

Bibb has maintained that he supported the goals of Tanisha’s Law but that the original legislation needed changes. After the legislation sat for a year without response, city council accused the mayor in December of dragging his feet.

This past Wednesday, council met again with Bibb’s public safety officials to hash out compromises on the law. If passed:

• Cleveland would create a new Bureau of Community Crisis Response within the Division of EMS. The city will hire a deputy commissioner this year to begin building the program.

• Those who call 911 must have a fourth option other than police, fire or EMS.

• Clinicians or mental health experts will respond to 911 calls along with EMS personnel, not police officers. And they’ll respond in plain vehicles and not ambulances.

• Care response teams can respond to a 911 call without the scene first being cleared by police. However, they can call for officers if needed.

The two main disagreements between the mayor and city council were whether to create a new standalone city department, and whether to wait for an analysis of 911 calls before moving forward.

Proponents wanted a standalone department so that future mayors and legislators would have a harder time dismantling the program, but the mayor’s office wanted flexibility to adapt the program over time.

The mayor’s office also wanted a better idea of call volume before moving forward. But city council points out that they authorized that 911 call analysis two years ago, and the mayor hasn’t even put out a request for contractors to do the analysis.

Safety Director Wayne Drummond told council he’d look to hire the new head of community crisis response once the legislation was passed. That new deputy commissioner will start the work of building care response teams ahead of that call analysis being finished.

Howse-Jones said that while a 911 call analysis would be helpful, it’s clear that Cleveland residents need care response so it makes sense to start creating the new bureau now. It can be expanded later to meet demand, she said.

She said once the new deputy commissioner is hired, she expects them to come back to city council and lay out a plan for hiring staff and a budget.

Initially, the legislation’s sponsors expected a new department to cost $800,000 annually to begin and $4 million once it was fully operational.

Councilman Charles Slife said city council will have to heighten its oversight to make sure the program is implemented as expected. While legislation can create city positions, only the mayor’s administration can make hires.

Slife sponsored Tanisha’s Law along with Howse-Jones and former Councilwoman Rebecca Maurer. It was first introduced in November 2024 to mark the 10-year anniversary of Anderson’s death.