Now, though, Binfaah is reconsidering. New rules passed by Congress last summer as part of President Trump’s signature tax legislation cap what Binfaah and students who pursue some advanced degrees, from teaching to social work, can borrow for graduate work to $100,000. That, she said, is not enough to pay for graduate school.

“I come from a low-income background. I’ll have to rely on loans. I don’t think $100,000 is reasonable,” she said. ”If I don’t have the means by then, I think I would just delay it, push things back.”

The new loan limit is part of a push by the Trump administration to rein in runaway tuition costs and the eye-popping levels of student debt so many graduates are struggling to repay. The rules apply not just to nursing but to nearly all graduate programs except for 11 degrees the government deems as “professional,” such as medicine, dentistry, and law. But those, too, are held to a strict loan cap of $200,000, still unlikely to cover the cost of attendance.

Few industries stand to be affected more than nursing, and that in turn could have a huge domino effect on one of the state’s most important and prestigious industries: health care.

Today, nurses are filling gaps in care left by other medical professions, providing a core function of care in a region where hospitals are among the largest employers and contributors to the economy.

And a greater number of nurses are responding to the need, attending graduate school to move up the career ladder, avoid burnout, and expand their earning power. Nurse practitioners, for instance, typically make around $120,000 a year in Massachusetts, 50 percent more than registered nurses without graduate degrees. By 2034, their ranks are projected to grow 60 percent here as physicians are in short supply.

Already, one in 10 nursing jobs in Massachusetts is vacant, according to the Massachusetts Health and Hospital Association. Studies warn that further reducing the ranks of advanced nurses would result in longer wait times, higher mortality rates, and greater reliance on emergency rooms that are already overwhelmed. Moreover, the loan caps could lead fewer people to pursue advanced degrees in specialties such as oncology, anesthesiology, and neonatal care at a time when that expertise is in great demand.

The new cap is “foolish and shortsighted,” said Joan Vitello-Cicciu, dean of the graduate school of nursing at UMass Chan. “It’s going to be a vicious cycle. People are not looking at all the unintended consequences.”

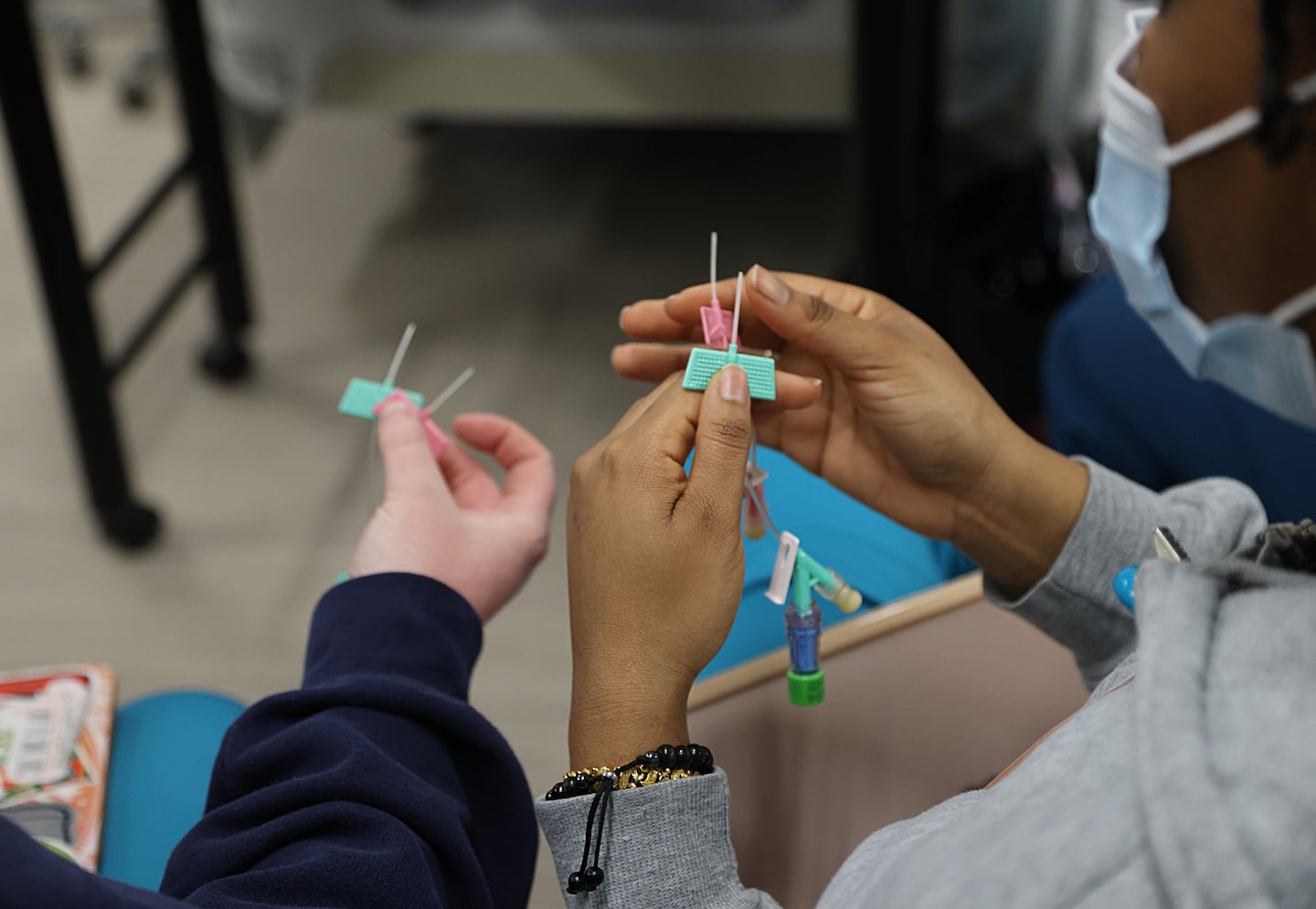

Medical equipment at the MGH Institute of Health Professions nursing class.

Medical equipment at the MGH Institute of Health Professions nursing class.

Suzanne Kreiter/Globe Staff

Federal officials say that leaving nursing and other fields outside the professional designation is not a “value judgement” on their importance. Only a sliver of the country’s 4.3 million nurses — including around 95,000 in Massachusetts — have graduate degrees, according to a fact sheet from the US Department of Education. Most who attend graduate school borrow less than $100,000, the department wrote.

The rule change, according to conservative think tank the American Enterprise Institute, is simply a “practical decision to ensure that nurses avoid excessive student debt burdens.”

But a recent survey by the American Association of Colleges of Nursing found that 82 percent of nursing students believe the loan limits will make it harder to finance graduate education. The group warned the burden will likely land hardest on low-income students who tend to borrow more money for higher education.

Sarah Romain, a nursing professor at Elms College in Chicopee, worries some students, particularly from working-class backgrounds, will eschew careers in advanced nursing.

“A fair number of the students that I have at Elms are working parents making basically minimum wage,” she said. “They really need a loan to get by … Plenty of nurses do very well, but the start is a struggle.”

In 2022, almost half of nurses pursuing advanced degrees used federally assisted loans, according to data from the Department of Health and Human Services. At least one-fifth of nursing graduate students borrow more than $100,000 to complete their degree, AACN found.

“I had lunch with [nursing] students in December,” said Julia Mason, chief nursing officer at Brigham and Women’s Hospital. “And they were worried about the future, about what they would be able to afford.”

Another factor is the rising cost of graduate nursing programs. Some estimates show that average nursing tuition is up by as much as 15 percent since 2020. Academic courses are increasingly complex, training equipment is expensive, and faculty salaries gobble up a sizable chunk of the budget at nursing schools, which compete for labor with better-paying hospitals and biotechnology companies.

Supporters of the new borrowing rules, and some nurses, said the limits will put downward pressure on tuition — a notion most higher education administrators dispute.

At MGH Institute of Health Professions, nursing students gathered for class. Suzanne Kreiter/Globe Staff

At MGH Institute of Health Professions, nursing students gathered for class. Suzanne Kreiter/Globe Staff

“I would love to move away from a debt-financed higher education system,” said Persis Yu, deputy executive director and managing council at Protect Borrowers, a nonprofit dedicated to improving the student loan system. “But that requires real investment in higher education, both on the federal and state level. What this does is restrict access on one end, without providing the funding on the other end.”

Dr. Robbie Goldstein, commissioner of the Massachusetts Department of Public Health, said in a statement, “the federal loan cap has the possibility of dramatically changing the applicant pool and advancing only those who can afford the high cost of education, leading to less diversity and lived experience among those who are able to work in the state.”

There’s also concern the caps could force more students toward lower-quality graduate nursing programs, said Maura Abbott, dean of nursing at the MGH Institute of Health Professions in Charlestown. (Tuition for an MGH nurse practitioner doctoral degree costs almost $60,000, and housing, equipment, and other expenses can push the cost of attendance much higher.)

“We know the outcomes for patients who receive care from those schools are not as strong as nurses who go to high-quality programs,” she said.

The rationale for excluding nursing and other professions from the list of “professional” degrees that are subject to the higher $200,000 borrowing limit dates to the Higher Education Act of 1965, which at the time designated just 10 graduate degrees that way. Among them were medicine, law, dentistry, theology, and podiatry, which typically require an advanced degree to practice. (Theology was included on the assumption students would pursue clergy positions with their degrees.) Fields such as business, teaching, social work, and nursing, where one could initially get a job with a bachelor’s degree or less, were left off the list.

That 1965 definition had never been used to determine who could borrow for federal loans, and how much — until now.

Congress pointed to this 1965 definition as a starting point to determine what fields should be considered in this professional category, although Congress did not explicitly say that only the original 10 degrees should be included. A committee writing the rules added clinical psychology, but no others.

Nursing students at the MGH Institute handled equipment in class. Suzanne Kreiter/Globe Staff

Nursing students at the MGH Institute handled equipment in class. Suzanne Kreiter/Globe Staff

Workforce needs were not a part of the decision-making process, said Alex Ricci, president at the National Council of Higher Education Resources, a member of the rule-writing committee. Since Congress is explicitly trying to limit loans, the group largely deferred to their initial guidance, he added.

“There was no nod in law for exceptions for areas of high need, and so we were limited in how expansive we could be,” Ricci said. “If we got that wrong, Congress has every opportunity to revisit their legislative language and make it more clear to the department and to the higher education community what exactly they meant and who should get access to additional loans.”

Now, some colleges are trying to drum up new sources for student loans, partnering with state governments, philanthropies, and both non- and for-profit lenders to supplement lost federal dollars.

Yale and the University of Pennsylvania have forged deals with private lenders in preparation for a dropoff in federal funding, Bloomberg reported. And at Regis College in Weston, donors stepped in to fund students in the Doctor of Nursing Practice program for two years.

“But there is still a significant loss of funding for future nursing faculty,” said Regis president Antoinette Hayes.

At the same time, other programs that help pay for advanced nursing degrees are disappearing. Public Service Loan Forgiveness — a program over half of nurses hoped to use in 2017, the most recent data available — has been scaled back significantly. Trump hopes to close the National Institute of Nursing Research, which helps fund some nursing PhDs. And the Nursing Faculty Loan Program, which offers loan forgiveness to nurses who teach for four years after graduation, is on an indefinite pause.

Together, the changes threaten to put a chilling effect on the pipeline for new nurses and nursing school faculty.

Melissa Anne DuBois, a nursing PhD candidate at UMass Chan, said her faculty loan funding for her final year of school is gone, a year earlier than she expected, forcing her to seek out private loans.

“I’m in a good place because it is only a couple of semesters,” she said. “But if this started in 2023, if this happened when I was starting to go back to school, this might’ve been the thing that made me go, ‘I guess this isn’t going to happen for me.’ ”

Binfaah, the nursing student at BC, already somewhat feels that way.

”When it’s time for me to go back to school, things are not going to be the same,” she said. “It honestly feels like, they don’t want me to go to school. That’s what it feels like.”

This story was produced by the Globe’s Money, Power, Inequality team, which covers the racial wealth gap in Greater Boston. You can sign up for the newsletter here.

Diti Kohli can be reached at diti.kohli@globe.com. Follow her @ditikohli_. Mara Kardas-Nelson can be reached at mara.kardas-nelson@globe.com.