This is the final part of a series on The Athletic taking the tactical temperature at each of the Premier League’s ‘Big Six’. How have each side evolved this season, what are they doing well, and what are the issues — if any — that need fixing?

Part one, on Manchester City, is here

Part two, on Arsenal, is here

Part three, on Tottenham Hotspur, is here

Part four, on Liverpool, is here

Part five, on Chelsea, is here

In one single Saturday afternoon, the gloom and despair enveloping Old Trafford was vanquished, replaced by a wave of ecstatic disbelief. Manchester United defeated neighbours Manchester City 2-0 at the weekend in Michael Carrick’s first game in interim charge, following Ruben Amorim’s sacking after 14 months in the job.

Amorim produced his share of marquee results during a turbulent spell in Manchester, but most — including the 2-1 defeat of champions Liverpool at Anfield earlier this season — were of the smash-and-grab variety.

Saturday, however, brought a comprehensive victory, and it would have been even more convincing had United’s forwards timed their runs fractionally better, with three further ‘goals’ ruled out for offside. Defensively, United conceded just 0.47 expected goals, which was City’s lowest tally for that metric in a Premier League game since February 2021.

It was a much-needed catharsis after the lows of Amorim’s reign, which ended with a record of 24 wins from 63 matches — just 38.1 per cent.

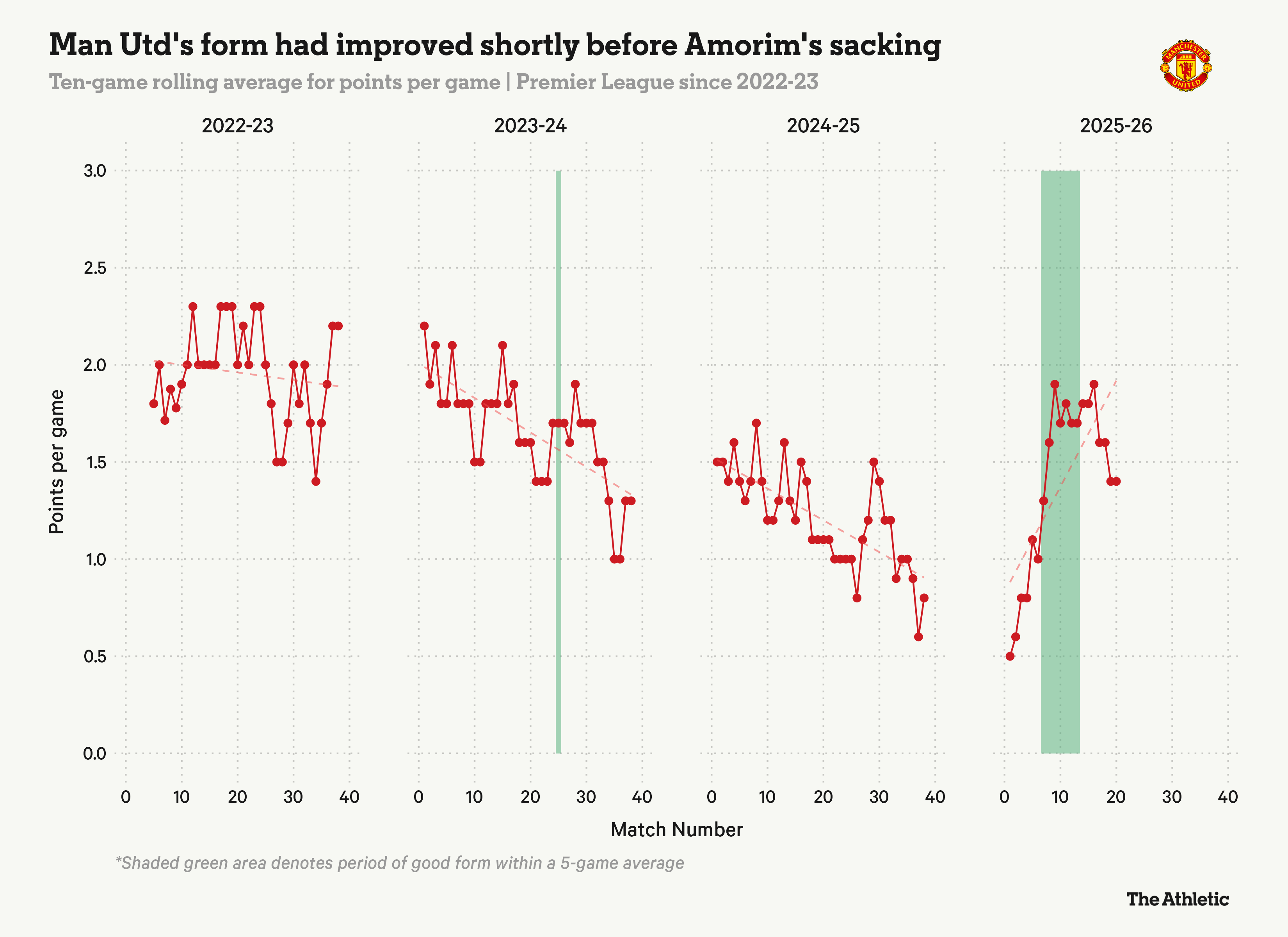

To Amorim’s credit, United’s form had improved this season, following their dismal 15th-place finish in 2024-25.

The graphic below plots their 10-game rolling average for points per game and shows a clear uptick in their results in the late autumn. The shaded green areas mark periods of ‘good form’, defined by The Athletic’s Mark Carey as any five-game stretch where the rolling average is more than one-third above the previous 38 matches.

The run started with the 2-0 home win against Sunderland in early October and ended with a 2-1 victory at Crystal Palace in late November. Amorim was named Premier League Manager of the Month for October midway through a seven-game stretch that brought four wins, two draws and one defeat.

Results dipped again thereafter, but there were mitigating circumstances.

Amorim’s final line-up, a 1-1 draw with Leeds United, featured wing-back Patrick Dorgu deployed as a makeshift inside forward in his renowned 3-4-2-1 system. Bruno Fernandes and Mason Mount were unavailable through injury, while Bryan Mbeumo and Amad — other more natural candidates for the role — were absent on Africa Cup of Nations duty.

When Amorim departed, United were sixth and just three points off fourth. Some of that improvement was simply a rebound from last season’s disastrous form, but the numbers stood up in their own right: United ranked third in the league for expected goal (xG) difference per game.

Even with those improvements, Amorim’s tactical vision never felt a wholly convincing fit for this squad. Carrick has overseen just one game so far, but has already made tactical adjustments that appear better suited to the players at his disposal.

Here, The Athletic breaks down Amorim’s tactical approach — what it was trying to achieve, where it fell short — and how Carrick has already begun to address some of those shortcomings.

Ruben Amorim has departed, but his imprint on the Manchester United squad is still strong (Darren Staples/AFP via Getty Images)

‘English football from the past’

Right from the off, Amorim tried — unsuccessfully — to downplay what would become the defining thread of his time in charge: the formation. “A lot of people talk about the 3-4-3 and the 4-3-3 and all that stuff,” he said in his first interview with the club’s in-house media. “The most important thing for me at this moment is to create the principles.”

Instead, Amorim argued that he used the 3-4-2-1 to “simply start from a base”, before his team would morph into various fluid systems higher up the pitch in an attempt to pull apart opposition defences.

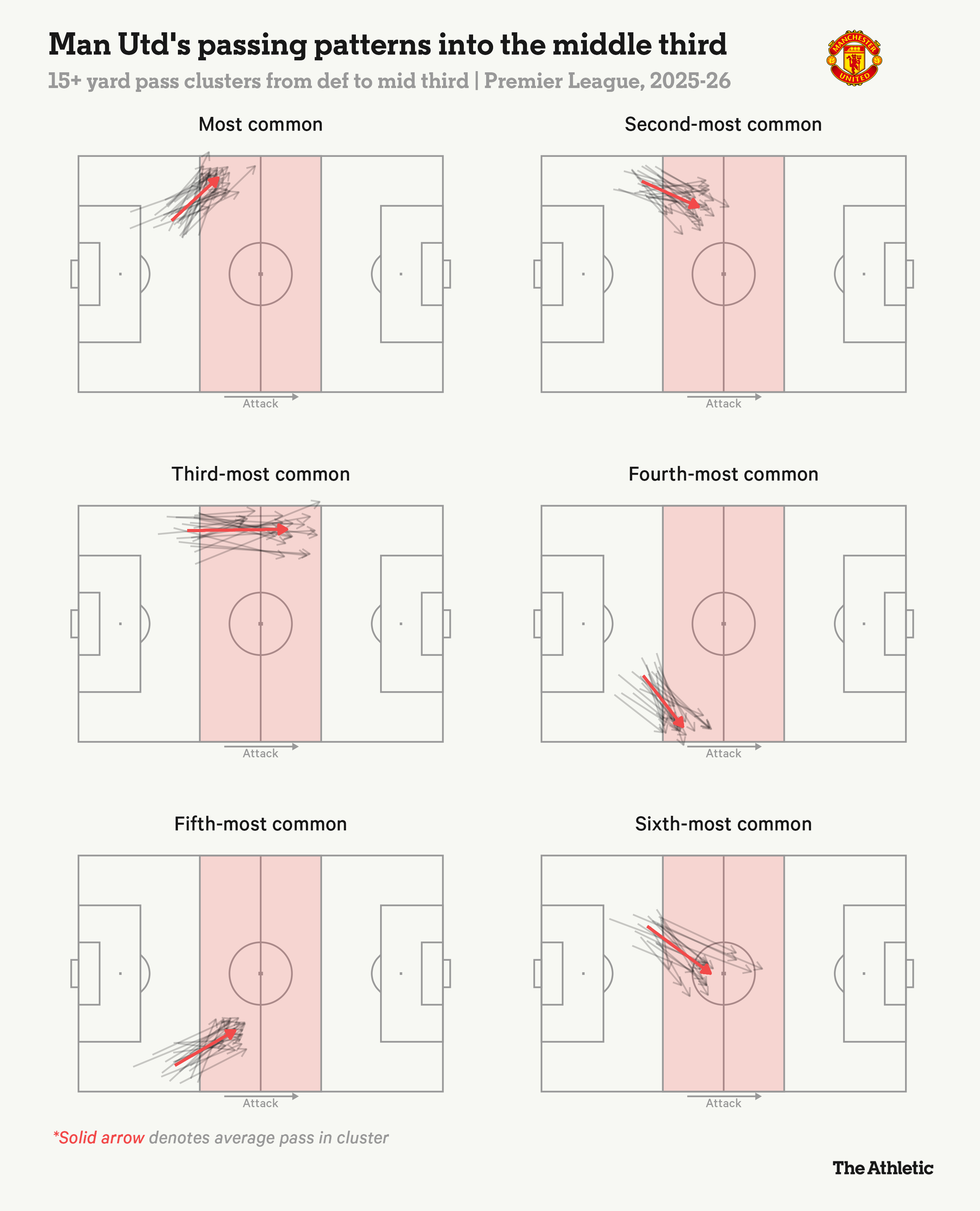

That “base” was most evident in United’s build-up play. Wing-backs stretched the pitch, offering easy outlets as the ball progressed from defence into midfield. Five of United’s six most common passing routes from the defensive third run through wide areas, underlining the importance of the wings in their build-up structure.

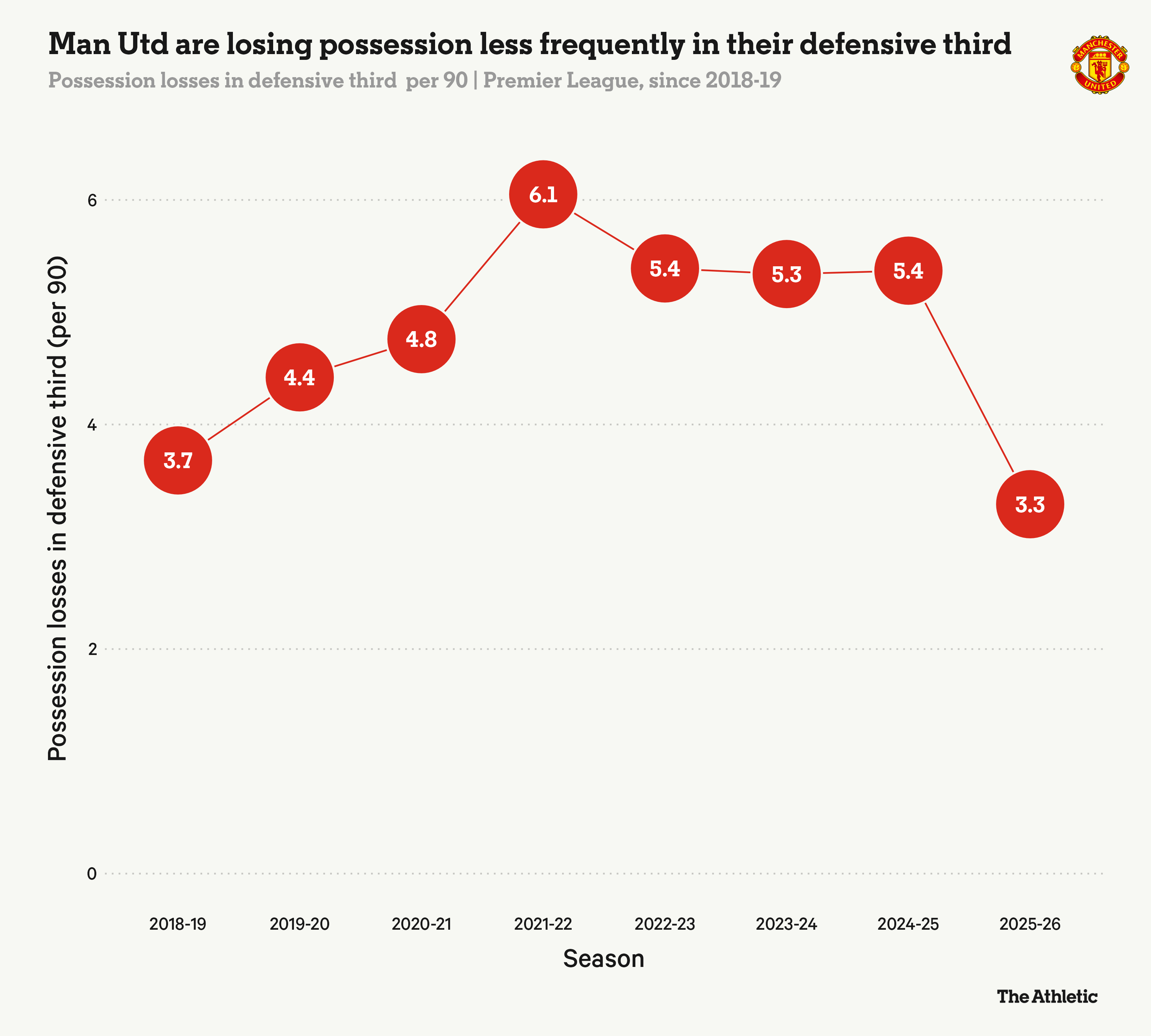

United experienced growing pains as they adapted to this unconventional setup. Across Amorim’s 27 Premier League games last season after succeeding Erik ten Hag in the November, they lost possession in their own third 5.8 times per match — a figure surpassed only by Tottenham (6.04 losses per match).

Despite a 1-0 home defeat against Arsenal, Amorim saw early signs of improvement in this area in the opening game of this season, with United more composed when circulating the ball. “We lost fewer balls in the build-up compared to last year, when we struggled a lot,” he told reporters afterwards.

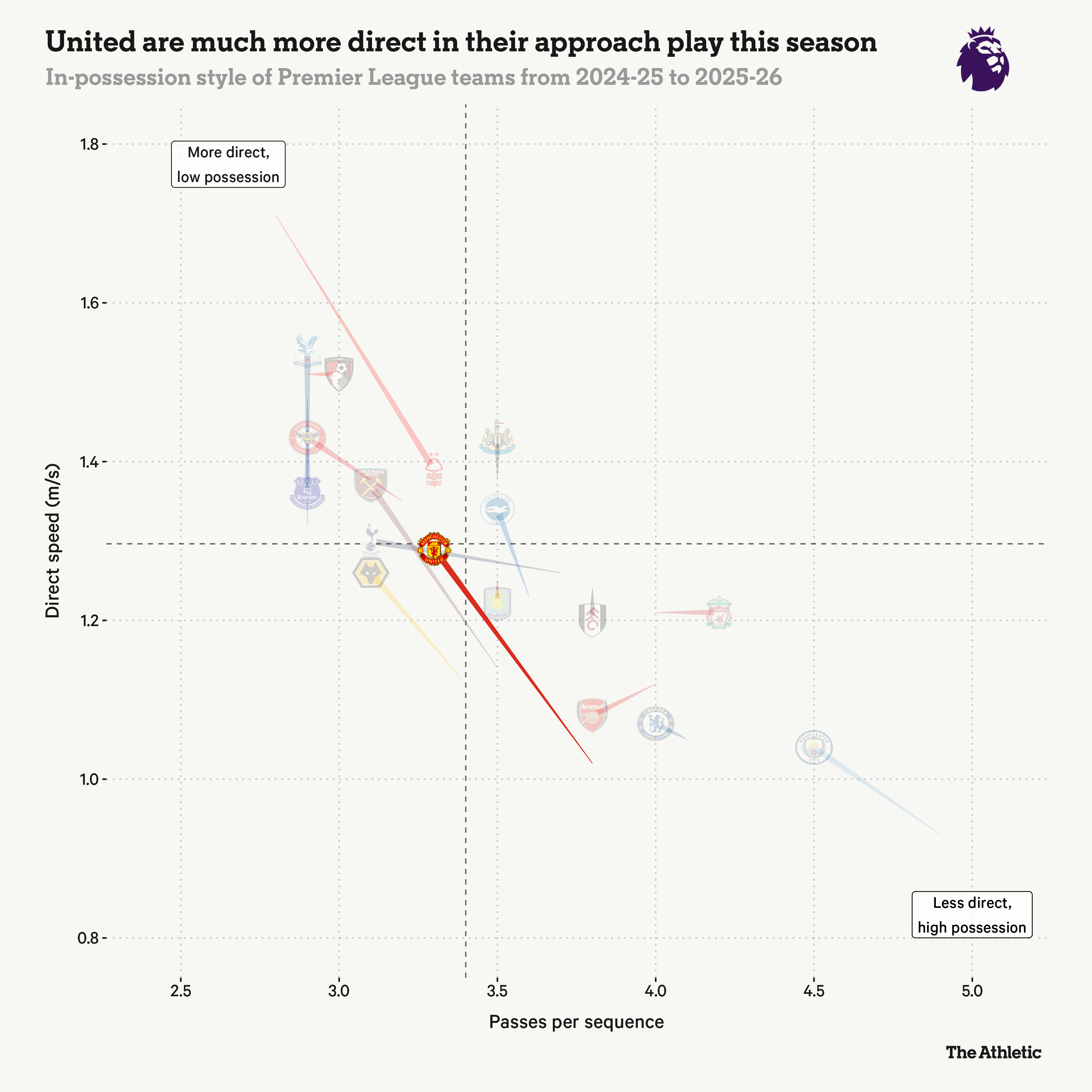

That improvement continued as the season wore on, with United sharply reducing those possession losses to 3.3 per match. Part of that was down to increased familiarity, but it also reflected a tactical shift towards a more direct approach. United gave opponents fewer opportunities to force high turnovers, eschewing patient build-up for a more direct approach.

United’s ‘direct speed’ — a measure of how quickly the ball travels upfield — rose from 1.02 metres per second last season to 1.29m/s, the largest increase among clubs competing in the Premier League across both campaigns. At the same time, their passes per sequence fell from 3.8 to 3.3.

“If you need a lot of touches, you will understand that you need a lot of touches,” Amorim said. “If you need one, put the ball. The fans want to see a different game. We are in England. I try to show you a little bit of English football from the past.”

On Saturday at Old Trafford, with City dominating possession but leaving gaps in transition, United leaned into that approach more than at any other point this season, recording a direct speed of 2.07 m/s and their second-highest long-ball share (15.2 per cent).

They rarely built from the back, finishing the game with a season-low 32.5 per cent possession. Carrick’s counterpunching tactics worked perfectly, but Pep Guardiola’s City are a special case. Most of United’s games will instead see them tasked with breaking down stubborn low blocks.

How Carrick navigates that challenge will shape his reign, but on this occasion he made a simple decision which should help: picking players in their natural positions.

Amorim showed a curious reluctance to trust Kobbie Mainoo, failing to start him in a league match this season, despite the 20-year-old academy graduate being United’s only naturally creative option in central midfield. To compensate for that imbalance, he dropped Fernandes into the double pivot, which helped with progression from deep, but meant that his Portuguese countryman’s talents were less visible in decisive areas of the pitch.

(Michael Regan/Getty Images)

Restored to his natural No 10 role on Saturday, Fernandes created six chances — his joint-highest tally this season — including a perfectly weighted through-ball for Mbeumo’s opener.

Improved wide combinations

United may show greater variety in how they reach the final third, but once there, the principles of their attacking play remained largely unchanged under Amorim. Instead of relying on individual dribbling to break down compact defences, they prioritised rehearsed combination play, with take-on completions falling from 8.18 per 90 minutes under Ten Hag to 6.18 with Amorim at the wheel.

A familiar wrinkle in these combinations is the use of third-man runners, with centre-backs punching passes into midfield to draw markers and release runners in behind. United’s 2.95 through balls per 90 minutes this season is their highest figure across the past eight campaigns.

Wide combination play is another familiar feature, and one that has sharpened this season. Increased time on the training ground has helped — Amorim repeatedly pointed to his lack of a pre-season with the players during that first year. Mbeumo’s summer arrival from Brentford as a right-sided No 10 has improved United’s ability to link play on that flank, with his relationship with Amad proving especially fruitful.

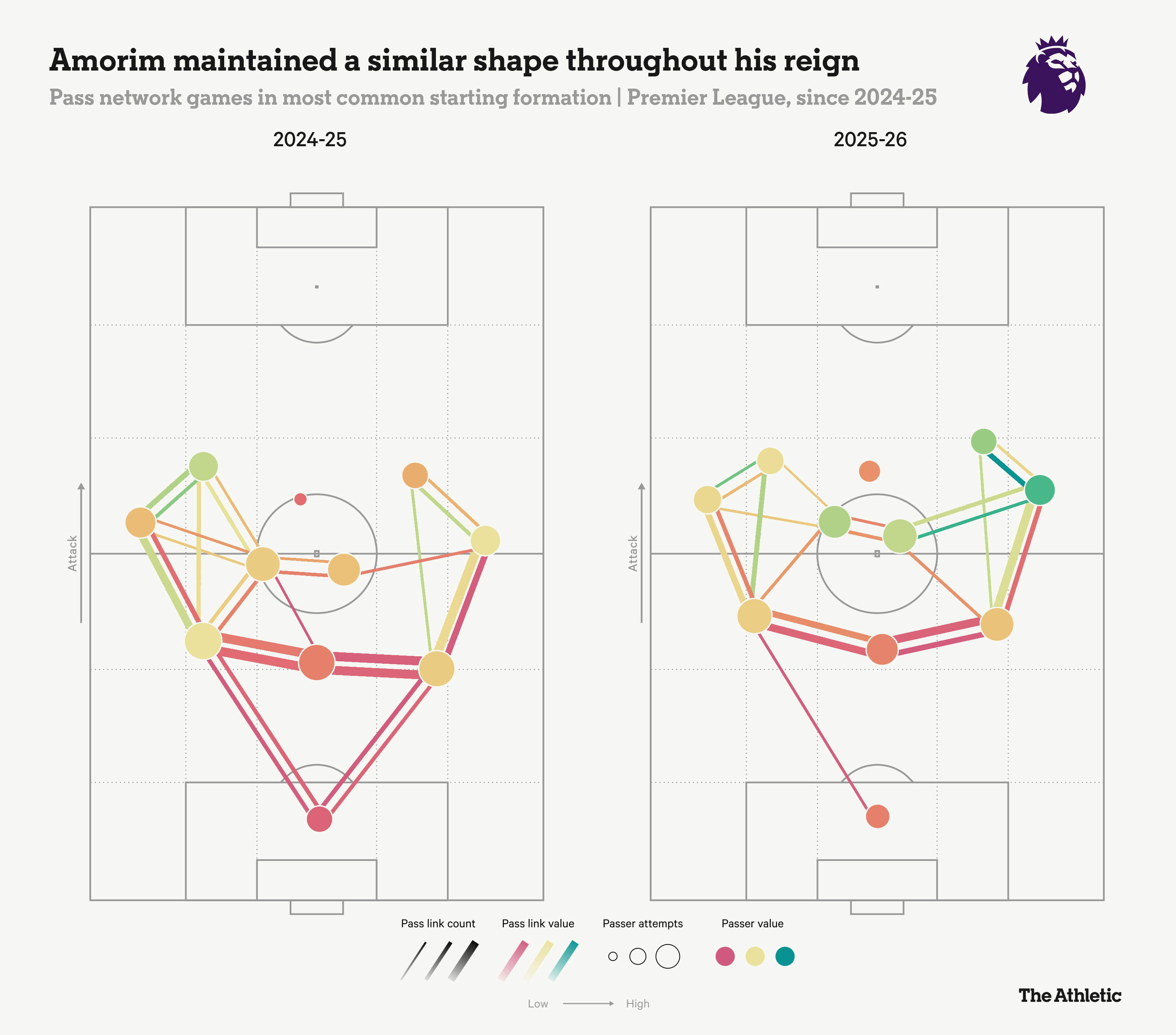

Below are the season-by-season passing networks for United under Amorim.

The overall shape for the two is remarkably consistent and familiar, but notice the difference in the line colouring. These links are shaded according to the quality of passes exchanged between players, with greener connections indicating stronger relationships. On the right side, the improvement is particularly pronounced.

Amorim’s setup was designed to create overloads. With the wing-backs high, United could crowd one flank, and on the right (this season), Mbeumo and Amad often rotated intelligently, pulling defenders wide to open space inside.

The GIF below shows both players executing this movement in the build-up to Mount’s goal in the 2-0 win against Sunderland.

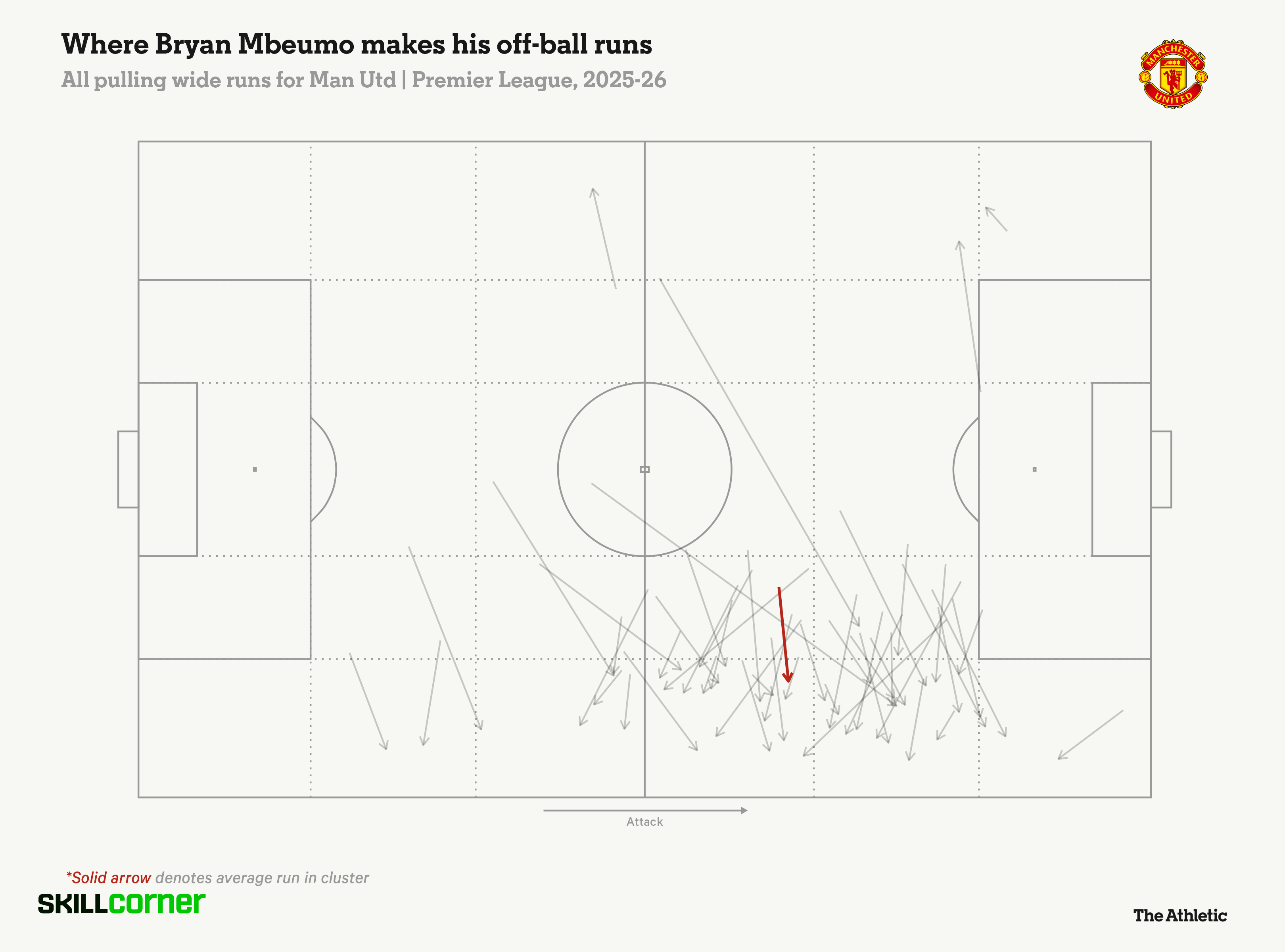

The frequency of these movements is reflected in the numbers.

SkillCorner defines a pulling-wide run as a movement that starts in the centre or half-space and ends in the wide channel, finishing wider than the player in possession. By that measure, Mbeumo leads United this season with 53 such runs, with Amad close behind on 44.

Before the 2-2 draw with Nottingham Forest in November, Amorim described his approach as “a numbers game”. But when opponents mirrored his structure with a back five of their own, those numerical advantages were harder to come by.

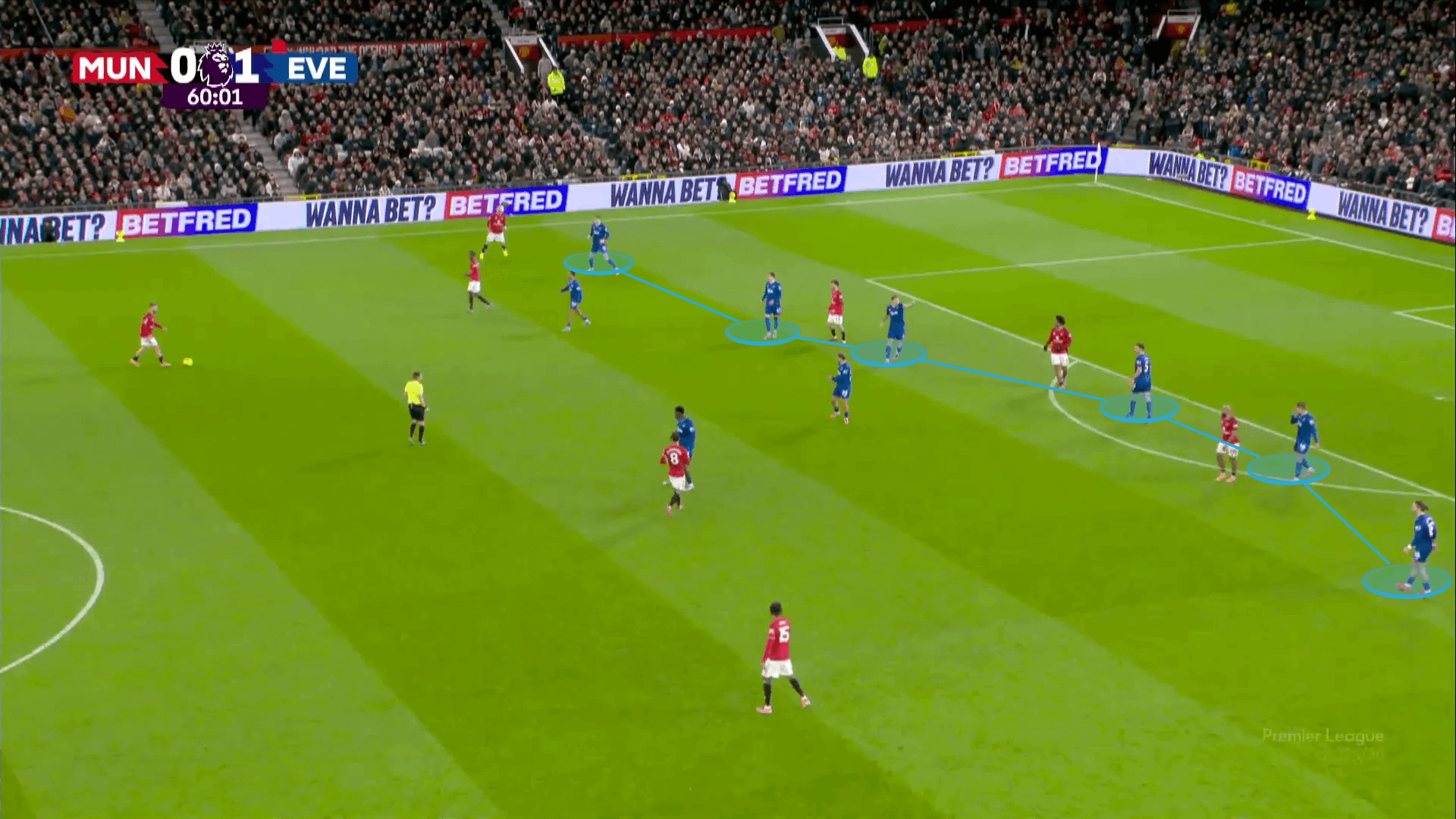

In November’s 1-0 home defeat against Everton, a game played largely against 10 men after Idrissa Gueye’s dismissal in the 13th minute, the opposition retreated into what was effectively a back six. United failed to commit a centre-back further forward to take advantage of their numerical advantage, and with few overload opportunities, the lack of individual spontaneity and risk-taking was glaring.

A soft centre

But the biggest thorn in Amorim’s reign was that, for all the extra protection of a back three, United still looked porous.

This issue was most keenly felt in central midfield. United’s double pivot often paired Fernandes — a creator rather than a defensive enforcer — with Casemiro, who, at age 33 (34 next month), can no longer cover the amount of ground he used to.

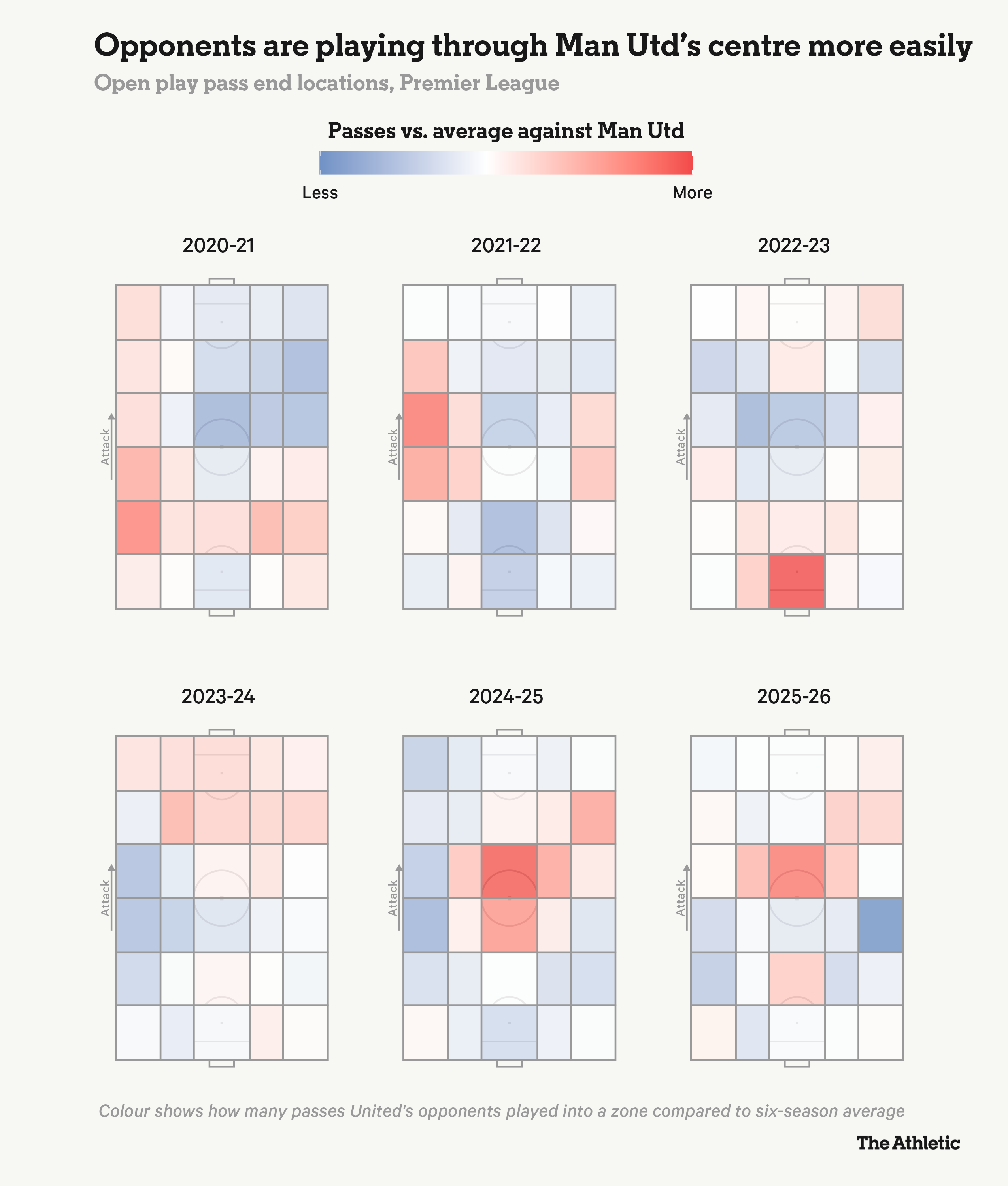

The pitch map below shows the percentage of passes played into different zones against United, compared with their six-season Premier League average, highlighting a soft central area.

United’s double pivot was often outnumbered by three-man midfields. To counteract this, one of the centre-backs is supposed to “jump” forward into midfield in mid-block situations, and restore numerical parity.

The timing of that movement proved difficult, though. Centre-backs were often hesitant to step out, a hesitation that teams exploited. “We knew that we would be able to get behind their two midfielders, and their three centre-backs wouldn’t want to jump,” Fulham midfielder Alex Iwobi said after the teams’ 1-1 draw at Craven Cottage in August.

Carrick, by contrast, simplified the demands on his centre-backs.

Rather than asking them to execute these risky forward jumps into midfield, United looked to plug gaps against City on Saturday through recovery runs from ahead of the ball. In the example below, Rodri picks out Phil Foden between the lines, but Patrick Dorgu is alert and sprints back from left midfield to close the space and win back possession.

![]()

Fernandes, who recorded 17 defensive actions against City — the third most in the match — was particularly diligent in this regard. “He had a disciplined role defensively as well, to protect the team from anything through the middle as much as possible,” Carrick said afterwards.

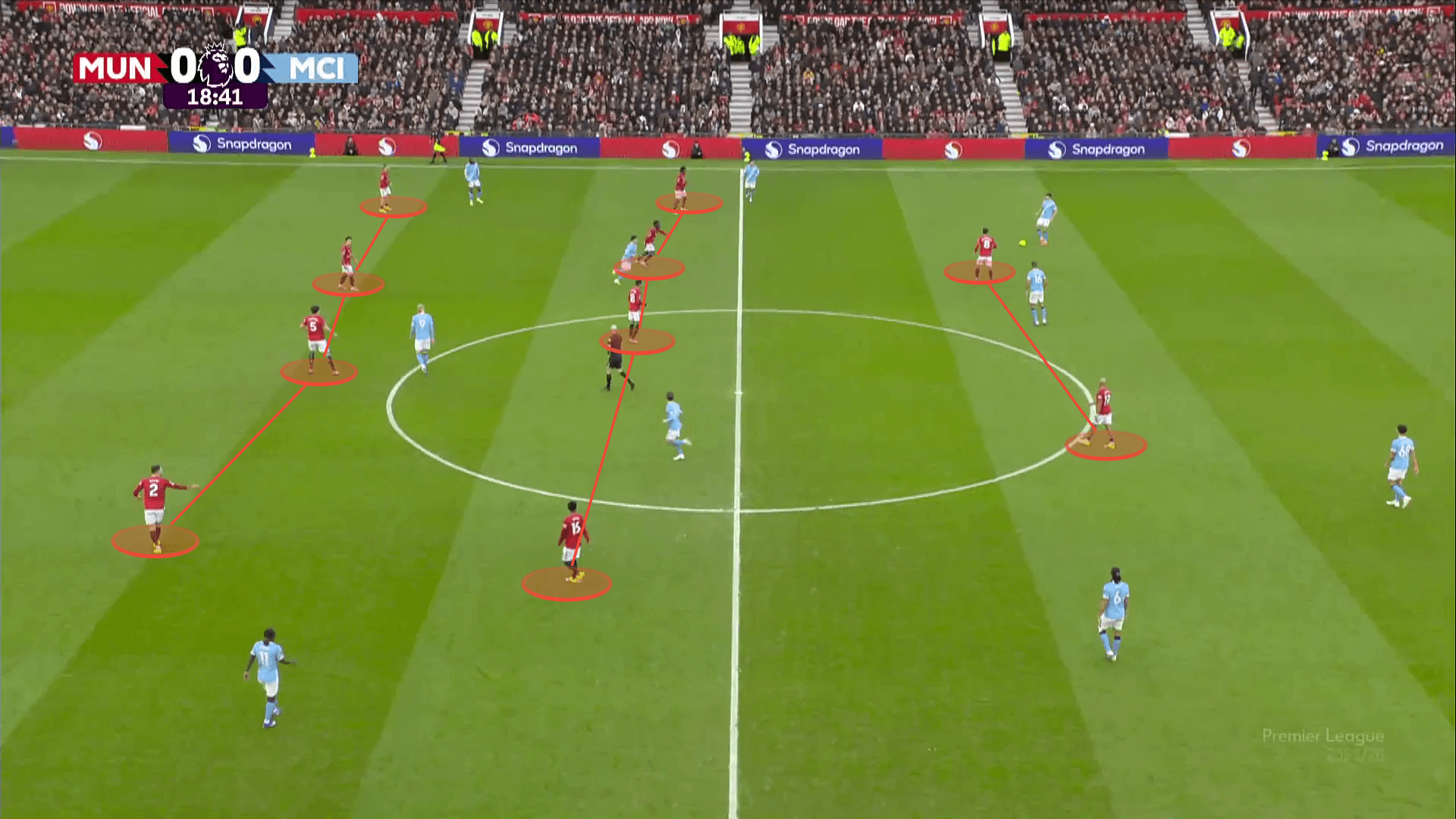

Overall, United showed few of the out-of-possession issues on Saturday that have plagued them this season. “We needed to be compact and needed the distances as short as possible between the units and between the positions,” said Carrick, and the image below shows the narrow 4-4-2 structure they adopted without the ball.

United did not simply drop deep and preserve this shape; they also disrupted City’s build-up through their pressing.

In the sequence below, Rodri drops deep to initiate play, but Mainoo steps out aggressively to track him, joining Mbeumo and Fernandes in the press. Behind them, Amad and Dorgu tucked inside alongside Casemiro to form a temporary three-man midfield.

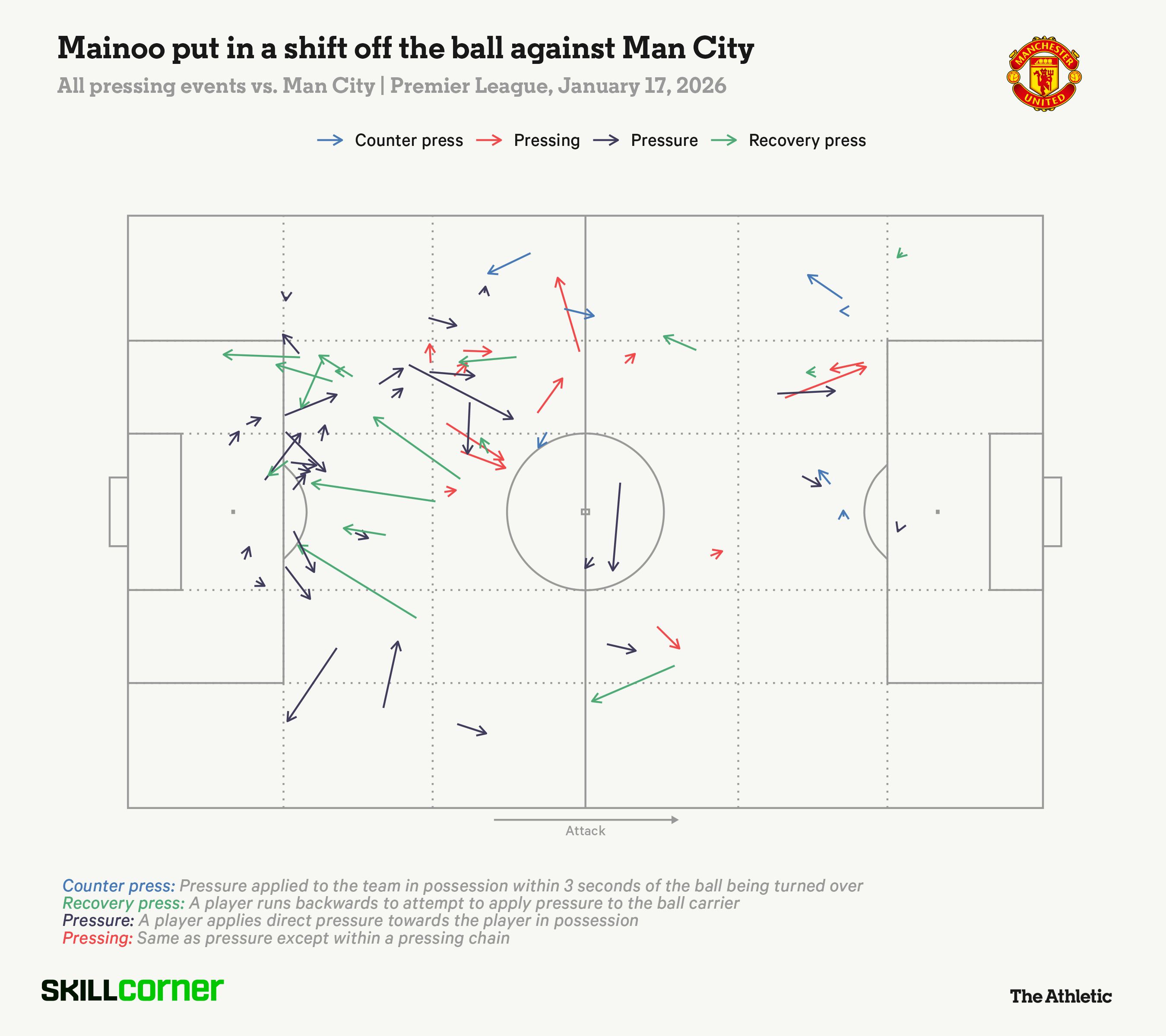

That dynamic of Mainoo pushing forward and Casemiro shifting across to screen the space behind allowed United to nullify Rodri’s influence without compromising their defensive solidity. Mainoo — frequently criticised by Amorim for his off-ball work — covered ground relentlessly, as shown by the map below of his pressing actions.

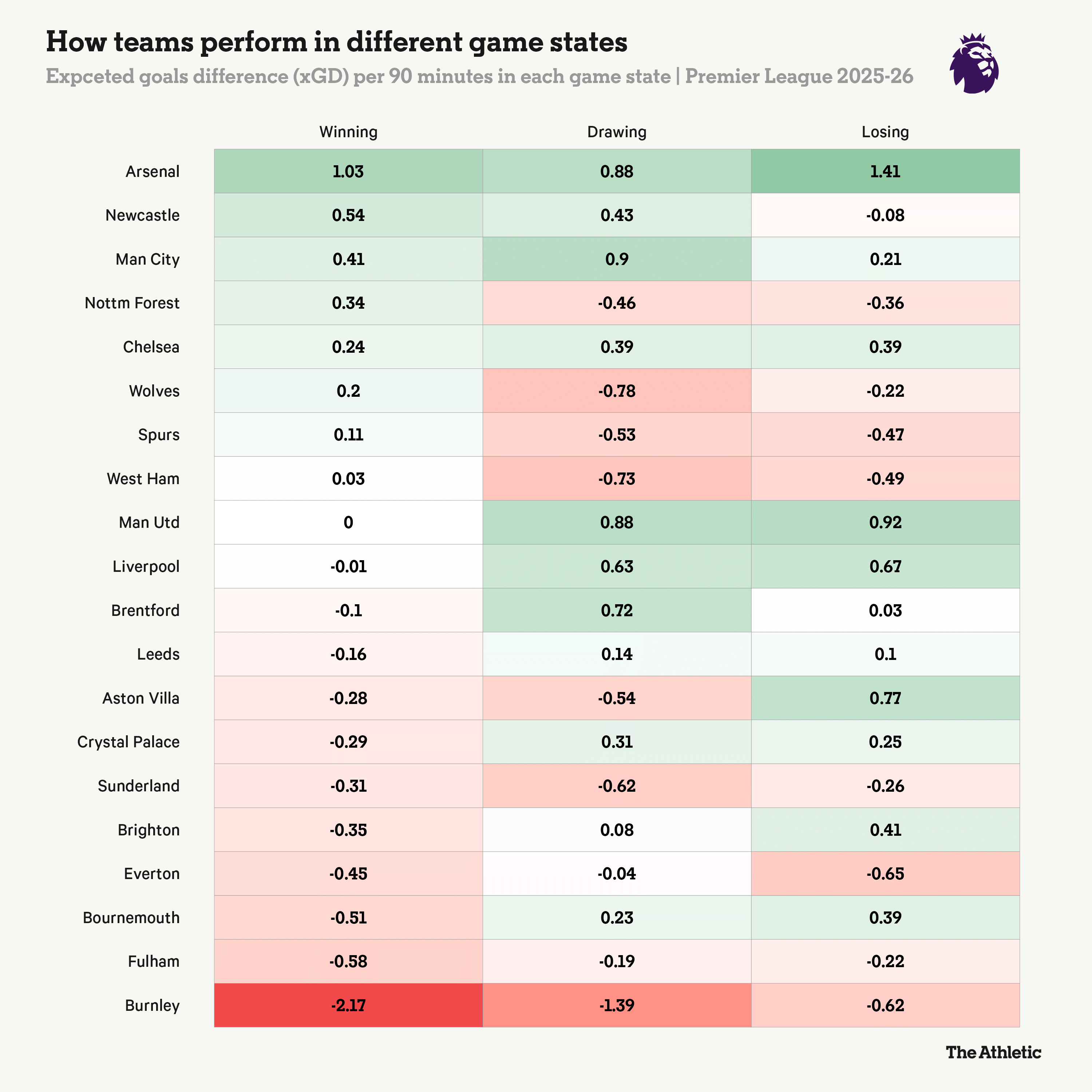

United also displayed a quality largely absent under Amorim: composure when ahead. As the graph below shows, United rank second in the Premier League for expected goal difference when trailing, and joint-second best when level, but struggle when in the lead.

They have dropped 14 points from winning positions this season, struggling to control the tempo to see out games. “It’s understanding of the game, and how to play the game in different moments,” said Amorim in his press conference after facing Bournemouth last month, a home game United led three times but ultimately drew 4-4.

On Saturday, they showed that understanding, remaining calm after taking the lead, and even more so once Dorgu doubled their advantage in the 76th minute. Composure was a theme Carrick was keen to stress in the post-match glow.

United have long been capable of producing landmark victories; where they have fallen short over the past decade is in backing them up with consistent performances across a campaign.

Even allowing for Carrick’s sensible caution, that derby win at the weekend offered enough evidence that he possesses the tactical nous to get this faltering United side back on track.