Hiroshima –

When the first atomic bomb dropped on Hiroshima on Aug. 6, 1945, physicist Albert Einstein was at his summer cottage in upstate New York, near Lake Saranac. Sixteen hours after pilot Paul Tibbets opened the hatch doors of the Enola Gay to release the first atomic bomb ever used against another country, U.S. President Harry S. Truman issued a prepared statement that was broadcast on radio stations across the United States.

At the time of the announcement, Einstein was taking a nap, but his secretary, Helen Dukas, had the radio on. When Einstein entered the room, it was Dukas who delivered the news. He fought back a deep sadness, then spoke two words in German: “Oh weh.”

Various translations exist: “Alas.” “Woe is me.” “Oh my God.” “And that’s that.” Literally, the phrase is used to express profound pain. The news had affected him deeply.

Most scholars or biographers who write about this period in Einstein’s life connect his anguish to being at least indirectly responsible for the bomb’s creation. In an Aug. 2, 1939 letter to President Franklin D. Roosevelt — the now-famous Einstein-Szilard letter — Einstein, by virtue of his signature, urged Roosevelt to “speed up the experimental work” on what would eventually become the atomic bomb.

Einstein did this believing the United States needed to stay ahead of Adolf Hitler’s Germany — Japan was still 28 months away from bombing Pearl Harbor. It was a letter he came to regret after World War II ended. In 1947, he said as much: “Had I known that the Germans would not succeed in developing an atomic bomb, I would have done nothing for the bomb,” he told Newsweek magazine.

What has largely been forgotten is that Einstein, in December 1922, visited Miyajima, now part of Hiroshima Prefecture. He met local residents, hiked a sacred mountain, visited shrines and saw — at least from a distance — the Hiroshima Prefectural Commercial Exhibition Hall designed by Czech architect Jan Letzel. Today, the building is known as the Genbaku Dome, or Hiroshima Peace Memorial.

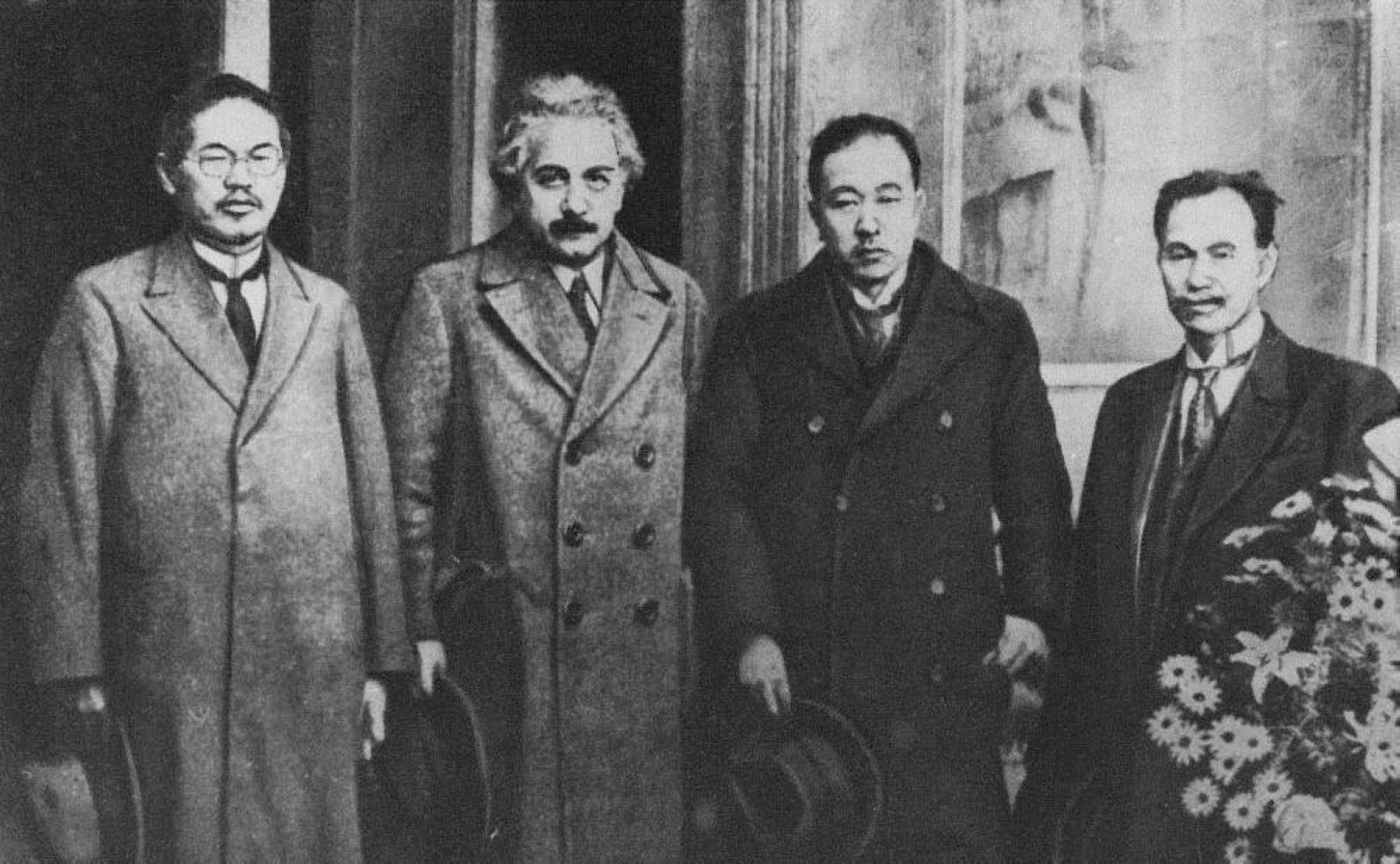

Albert Einstein (second from left) visited Tohoku University in November 1922. He is seen here with (from left) metallurgist and inventor Kotaro Honda, physicist Keiichi Aichi and geophysicist Shirota Kusakabe.

| PUBLIC DOMAIN/ VIA WIKIMEDIA COMMONS

Einstein’s five-week trip to Japan transformed the way he thought about Japanese culture and its people. When he later said “Oh weh,” he knew exactly where the bomb had been dropped and what it had destroyed — because he had been there.

By pairing local newspapers, archival sources and a site visit I made in April 2025 with Einstein’s diaries of the trip, it is possible to trace his movements during the three days he spent in Hiroshima. He was 43 years old and at the peak of his fame. His second wife, Elsa, accompanied him.

Getting to Hiroshima

On Nov. 17, 1922, the Kitano Maru docked in Kobe. Einstein and his wife were met by large crowds. A press conference followed, then a respite at a hotel in Kyoto. When the couple reached Tokyo, the intensity of the attention drained what energy he had left: “Arrival at hotel, completely exhausted among gigantic floral wreaths and bouquets. Still to come: visit by Berliners and burial alive.”

Over the next few weeks, Einstein toured the main island of Honshu, his rock-star level of fame evident at nearly all 15 of his lectures. From Sendai to Fukuoka, his theory of relativity was met with what he described as “immense interest.”

During the lectures, Einstein spoke in German for about 15 minutes while his translator, Jun Ishiwara, took notes. Einstein would then pause, allowing Ishiwara to interpret his words for the packed audience. In a Dec. 14 lecture on a frigid, snowy day at Kyoto University, Einstein attempted to explain how he developed his theory of relativity. As he had in countless talks before, he cited “the strange result of the Michelson experiment,” along with a favorite anecdote from his time at the patent office in Bern in 1907, when he was struck by the idea that “if a man falls freely, he should not feel the weight himself.”

Einstein spoke at universities and public lecture halls, meeting with hundreds of Japanese officials and faculty members. No country he had visited since leaving Germany, however, impressed him more. “The Japanese do appeal to me,” he wrote from Kyoto on Dec. 17 to his sons, Hans and Eduard, “better than all the peoples I’ve met up to now: quiet, modest, intelligent, appreciative of art, and considerate; nothing is for the sake of appearances, but rather everything is for the sake of substance.”

He was even more candid two days later in a letter from Nara to his friend Michele Besso. Einstein felt confident enough to suggest that he understood Japan better than Lafcadio Hearn had — even though he had been there only a few weeks. “Not as mysterious as Hearn sees … but they are delicate and natural.”

From Nara, Einstein and Elsa traveled overnight by train “from 6 p.m. to 6 a.m.” to Hiroshima Prefecture. In the early morning hours of Dec. 20, after a 15-minute motorboat ride, they arrived “in the dark” on the island of Miyajima — about 20 kilometers from central Hiroshima — and checked in at the Miyajima Hotel.

The sacred island

Until 1868, when Emperor Meiji began the painful process of modernizing Japan, no one was allowed to be born or die on the island of Miyajima. If a pregnant woman was about to give birth, she was taken by boat to the mainland to deliver her child. If an elderly resident grew weak or ill, they were removed from the island before death. For nearly 18 centuries, Miyajima existed in a state of suspended animation — immortal, in this sense.

After half a century of industrialization, however, these and other sacred strictures gave way to practical considerations, including tourism. Still, by the time Einstein arrived at his hotel at 6 a.m. on Dec. 20, 1922, the island retained a fable-like quality — and does to this day. His itinerary planners had intended these few days to serve as a period of rest and recovery after three exhausting weeks of crowds and lectures.

Einstein’s guide and interpreter was 28-year-old Morikatsu Inagaki, whom Einstein referred to in his diary as “Gaki.” Inagaki had been at Einstein’s side for the previous month, interpreting anything Einstein said in public or in conversation — the technical lectures on relativity were Ishiwara’s job. Fluent in German — his wife was German — Inagaki developed such an easy rapport with Einstein that the two became lifelong friends.

Inagaki’s language skills and political connections were formidable. They had been strong enough to place him on Japan’s executive committee during post-World War I negotiations connected to the establishment of the League of Nations in 1920. Both men believed that a world government was the only viable path toward international cooperation and lasting peace.

After sleeping until 10 a.m., Einstein and Inagaki took a 10-minute walk from the hotel to Itsukushima Shrine. In his diary, Einstein noted that “from 11-12,” he took an “enthralling walk along the coast to the temple with graceful pagoda, built in the water (tidewater region).”

A photo taken at a commemorative dinner in Japan on Nov. 29, 1922, with Albert Einstein (front row, seventh from left) and his wife, Elsa (front row, ninth from left).

| UMUT EXHIBITION, PUBLIC DOMAIN VIA WIKIMEDIA COMMONS

Itsukushima Shrine has existed in some form since the late sixth century. Now a UNESCO World Heritage Site, the shrine’s spiritual purpose has long been to protect the island from maritime disaster and conflict.

At noon, Einstein encountered a different kind of conflict in the form of a telegram. The German ambassador, Wilhelm Solf, informed him that Maximilian Harden — a Jewish journalist who had been stabbed two weeks after the assassination of politician Walther Rathenau by antisemitic extremists — had stated during his trial that “Professor Einstein went to Japan because he did not consider himself safe in Germany.”

While Einstein did feel gravely threatened at the time, his motivations for traveling to Japan had largely been kept private. Now that Harden had made them public, Einstein knew he would have to respond — carefully.

After receiving the telegram, Einstein, deep in thought, set out with Inagaki on a hike to the summit of Mount Misen. By matching his diary entries with the three possible routes, it is likely that the pair took the Daishoin Trail, named for the Shingon Buddhist temple complex at the mountain’s base.

The hike is steep and took me about two hours to complete. A stone torii gate and stone steps were added in the early 1900s, financed by Prince Hirobumi Ito, who served as Japan’s prime minister from 1900 to 1901. “Along the way,” Einstein recorded, he encountered “countless small temples dedicated to natural deities.”

With Inagaki explaining the meanings of the stone figures they passed, Einstein found the hike “delightful,” noting with relief that “the entire path of steps” had been “hewn into granite rocks.” Inagaki also told him the trail was a “memorial to (the) Japanese love of nature,” dotted with what Einstein described as “all sorts of endearing superstitions” — including the stacking of stones to help the souls of children who die before their parents escape limbo and reach paradise.

At the summit, Einstein enjoyed a “wonderful view over the Japanese Inland Sea.” The unobstructed vista, full of the “subtlest of colors,” allowed him to see downtown Hiroshima in its entirety.

Albert Einstein and his wife, Elsa, enjoy Japanese hospitality on their visit to the country in 1922.

| PUBLIC DOMAIN/ VIA WIKIMEDIA COMMONS, COURTESY OF MEIJI SEIHANJO, SCANNED FROM “ALBERT EINSTEIN: CHIEF ENGINEER OF THE UNIVERSE: ONE HUNDRED AUTHORS FOR EINSTEIN”

The view from Mount Misen remains extraordinary, and much of what Einstein encountered along the Daishoin Trail endures today, largely unchanged from how it appeared more than a century ago.

After the hike, Einstein returned to the hotel and drafted a reply in German to Solf. Harden’s statement, he wrote, would make his life more “awkward.” Harden, Einstein admitted, was not “completely right” but also not “completely wrong.”

“A yearning for the Far East led me, in large part, to accept the invitation to Japan; another part was the need to get away for a while from the tense atmosphere in our homeland for a period of time, which so often places me in difficult situations,” Einstein explained. “But after the murder of Rathenau I was certainly very relieved to have an opportunity for a long absence from Germany, taking me away from the temporarily heightened danger without my having to do anything that could have been unpleasant for my German friends and colleagues.”

On Dec. 21, Einstein again immersed himself in Miyajima’s natural beauty, setting out on a “coastal walk with brilliant sunshine” alongside Inagaki and the well-known artist Ippei Okamoto. Okamoto had been sketching Einstein throughout his trip, with many of the drawings appearing in what was then Japan’s largest newspaper, the Tokio Asahi.

At one point, Einstein stopped to help several children fix a kite, untangling the strings so it could fly. Once the kite was ready, the children waited eagerly for the wind to rise. After several awkward minutes, it did not. Einstein moved on.

A “walk in (the) woods” followed, as did a “jellyfish hunt with rocks” with Inagaki and Okamoto. The next day, Sanehiko Yamamoto, the publisher of Kaizo magazine and the patron who had financed Einstein’s visit, arrived on Miyajima. On Dec. 22, Einstein took additional walks in the woods, completed a “wooden block puzzle” and narrowly avoided disaster when a small coal fire filled the room with anthracite fumes, leaving the group — including Elsa — mildly “intoxicated.”

At 4:10 p.m. on Dec. 22, Einstein and Elsa departed Miyajima by ferry. A week later — after “being photographed for the 10,000th time,” delivering a lecture in Fukuoka Prefecture, playing his violin for children at a YMCA on Christmas and staying at a hotel in Moji where “everything (was) separated by paper sliding doors that a little finger could easily shift aside” — the couple boarded a ship and left Japan.

“I loved the people and the country so much,” Einstein later told his secretary, “that I could not restrain my tears when I had to depart from them.

The author of the article would like to thank Yukiko Morikawa and Shun Arai for help with Japanese translations; Mara Peppmüller for help with German translations; and Sophie Qano and Mariko Kikuchi for their help along the Daishoin trail.