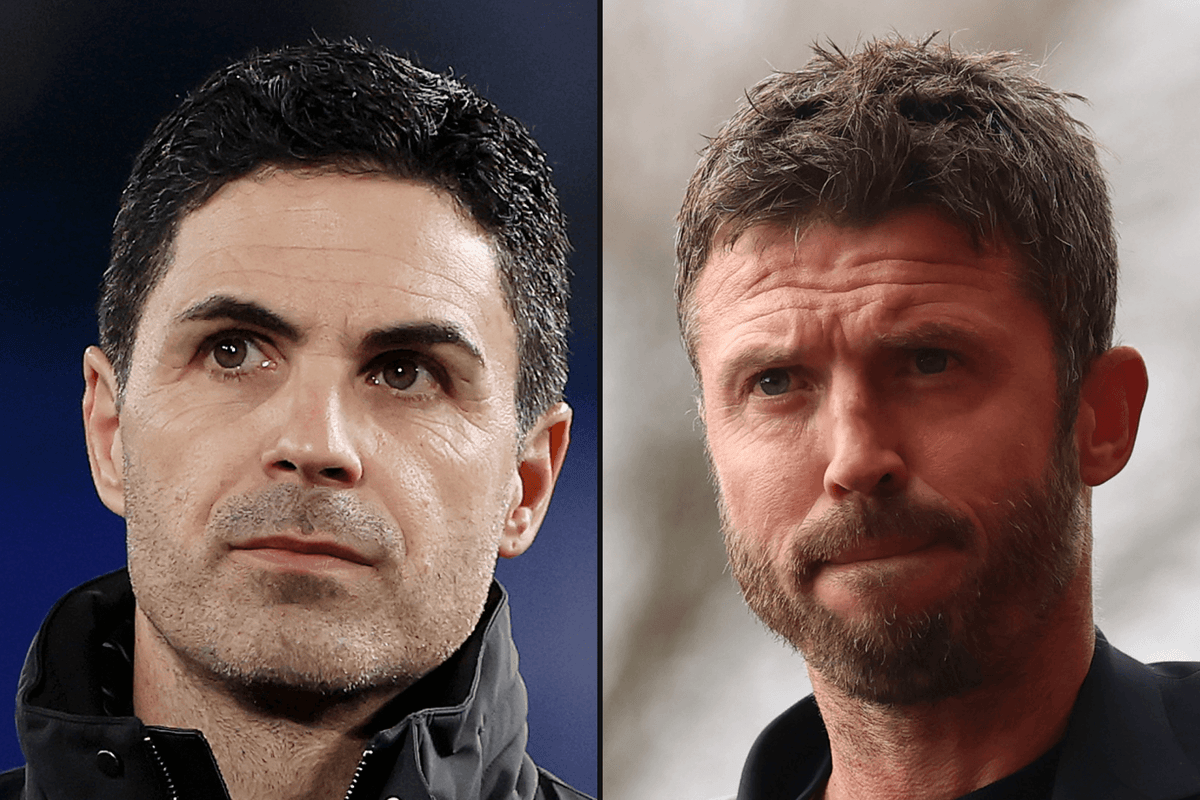

If someone had told you, when Mikel Arteta and Michael Carrick were anchoring the Arsenal and Manchester United midfields 10 to 15 years ago, that they’d one day be the managers in a fixture between those two clubs, you’d quite probably have said… ‘Hmmm, yeah, that seems about right.’

You can never guarantee that players will go into management, and you can never be sure those who do will put themselves in a position to be in the frame for top jobs. But somehow, based solely upon style of play, you’re rarely surprised by the type of footballers who do go on to become managers.

Arteta and Carrick are in very different places as managers, of course. Arteta is on course to steer Arsenal to their first Premier League title since long before the period he played for the club. Interim head coach Carrick only has a job until the end of the season as things stand, and United are desperately short of the level he was accustomed to as a player for them, when he helped win five league titles and a Champions League.

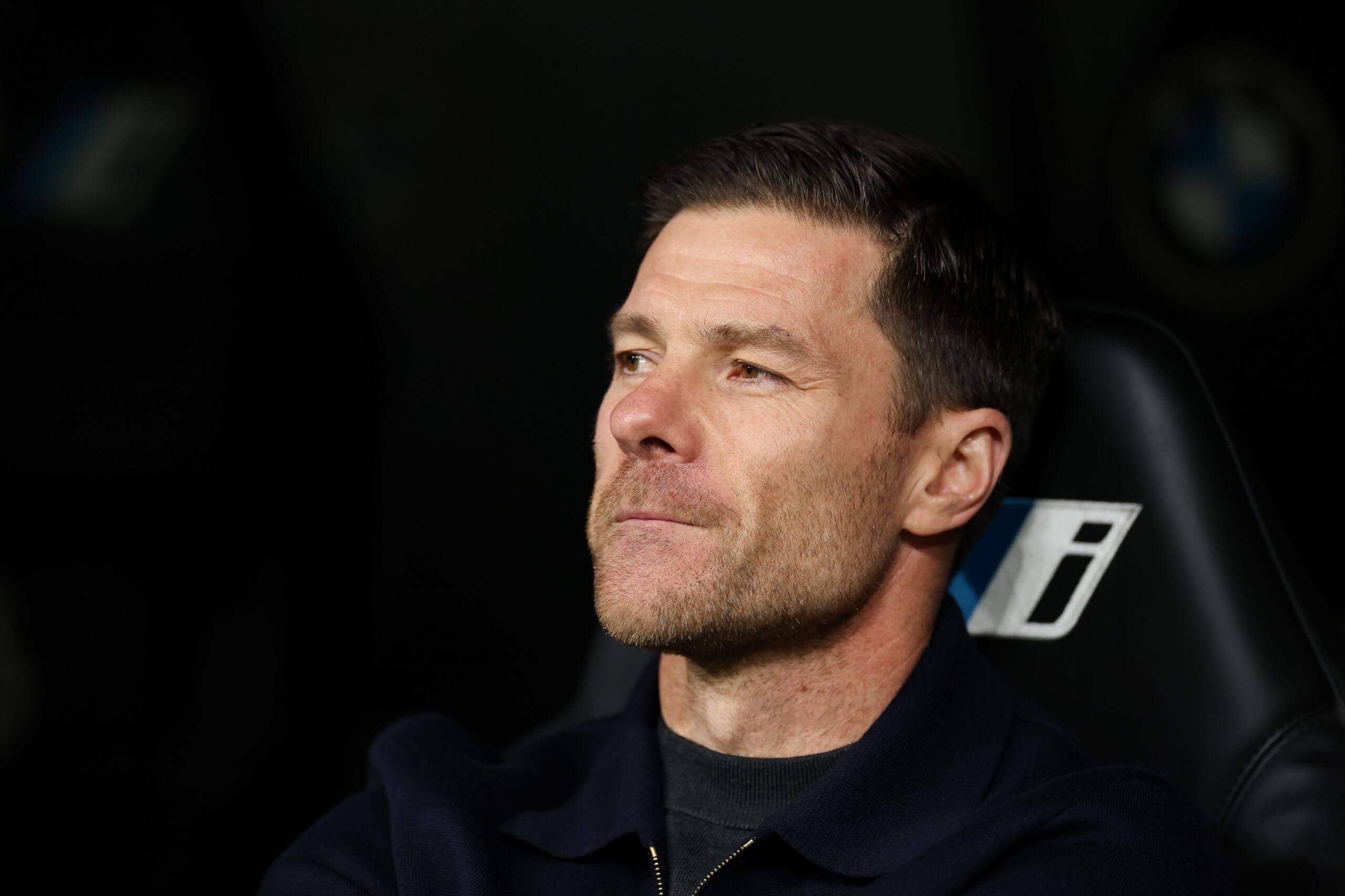

But if anyone was likely to be in charge of these two clubs, this pair fit the bill perfectly. And, for that matter, if you’d been asked to predict which two Real Madrid players from 15 years ago would be in charge of them this season, you might well have picked the intelligent, deep-lying midfielder Xabi Alonso, and the tactically flexible, highly-disciplined full-back Alvaro Arbeloa.

Alonso is another manager of a similar age and playing profile to Arteta and Carrick (Florencia Tan Jun/Getty Images)

Of the 27 managers to have taken charge of a Premier League side this season who had some form of professional playing career (which is nearly all of them), there’s a distinctly uneven spread if you look at their on-pitch positions. Fourteen were midfielders (most of them of the defensive rather than the attacking variety) and 11 were defenders (six centre-backs, five full-backs). Only one, Nuno Espirito Santo, was a goalkeeper. And only one, Daniel Farke, was a centre-forward and — with respect to him — he played at a rather low level in the German league system.

There is some logic to that.

Central midfielders, probably more than anyone else on the pitch, need to have a good tactical understanding of the game. They need to constantly be thinking about every aspect of play. Defenders, meanwhile, are playing an inherently reactive role; they need to read the flow of a match, anticipate opposition and make sure they’re working as part of a unit, rather than as an individual.

But there’s something slightly more specific: almost all successful managers were, as a player, slow. Or rather, they played in a way that was not defined by their pace or ability to get around the pitch.

Football is clearly a physical and technical sport, but it’s really a psychological and tactical sport. As Johan Cruyff said, “You play football with your head, and your legs are there to help you.”

Cruyff is — as it happens — one of the few examples of a highly successful manager who was fast as a player, although even then, he was more celebrated for his cerebral genius than his physical capacities. Still, it’s extremely rare to find a former winger, or a wide attacker, or a player who relied on speed in behind — a Michael Owen figure — popping up as a manager.

Almost every manager seems to have been slow.

Farke? “I was probably the slowest striker in Western Europe,” he once said in a Soccer AM interview.

Pep Guardiola? “I was a slow midfielder, I had no shot, no dribbling, poor aerial play, I wasn’t fast,” he once said.

Arne Slot? “One of Slot’s hang-ups was his lack of pace,” wrote his biographer, Maarten Meijer.

Fabio Capello? “He had an uncanny ability to read the play and pick out passes,” wrote his biographer Gabriele Marcotti. “His only weakness was a lack of pace.”

Even, say, Tony Pulis? “The slowest runner I ever saw,” remarked Bobby Gould, one of his old managers.

Arne Slot – not the quickest (VI Images via Getty Images)

We could go on. Arteta and Carrick weren’t desperately slow footballers — they played several hundred games at the top level, to start with — but they played the game in a manner that didn’t rely on speed or mobility.

In truth, both were fortunate to peak in the years when football was, more than ever, based around the patient possession play epitomised by the Barcelona and Spain sides of that era, although in a sense, both felt slightly on the periphery of things. Arteta was never capped by Spain at senior level (it’s not unreasonable to suggest that if he’d played in any other position or in any other era, he probably would have been) while Carrick had a strange 34-cap England career, always seemingly on the outside looking in. He only ever started one tournament match: a 1-0 win against Ecuador in the round of 16 at the 2006 World Cup, after which he received rave reviews for his passing quality, but was nevertheless dropped for the quarter-final.

Still, in Premier League terms, both excelled. And in their pomp, an era when in-depth statistics were becoming available to the public for the first time, it was notable that they figured highly in the passing stats. In 2012-13, for example, they were two of the three most prolific passers in the division. (The other, their fellow midfielder Yaya Toure, is currently on his own coaching journey, as an assistant with the Saudi Arabian national team.)

Both Arteta and Carrick probably enjoyed a couple more years playing at the top than they would in the modern era, when the focus on pressing means high-intensity sprints are a bigger factor.

Arteta and Carrick in action for Everton and Manchester United in 2010 (Andrew Yates/AFP via Getty Images)

Alonso and Xavi, two midfield greats of that era, have already won one of Europe’s big five domestic leagues as a manager/head coach, with Bayer Leverkusen and Barcelona respectively.

OK, if it was so simple to identify future managers a decade or so ago, then how about predicting the next generation from the current crop?

Maybe the most obvious candidate will be involved when Arteta and Carrick pit their wits against each other at the Emirates Stadium this weekend: Martin Zubimendi. The Arsenal and Spain midfielder plays the right position. He depends upon reading the game as much as his physical attributes. He played under Alonso, one of his idols, in the Real Sociedad youth system and is now managed by Arteta. And being Basque seems to help — as well as the aforementioned duo, the likes of Unai Emery and Andoni Iraola come from that region straddling the Spanish/French border.

Other names spring to mind: Bernardo Silva, Granit Xhaka, perhaps Casemiro, too.

But maybe the 100mph nature of the modern game means there is less room for the likes of Arteta and Carrick now. Players have to think faster, certainly, but they also need to run faster.

In that respect, that period around 2010 — the time when top-level football was briefly obsessed with pure passing midfielders in the Spanish style — was a particularly fertile period for future managers.