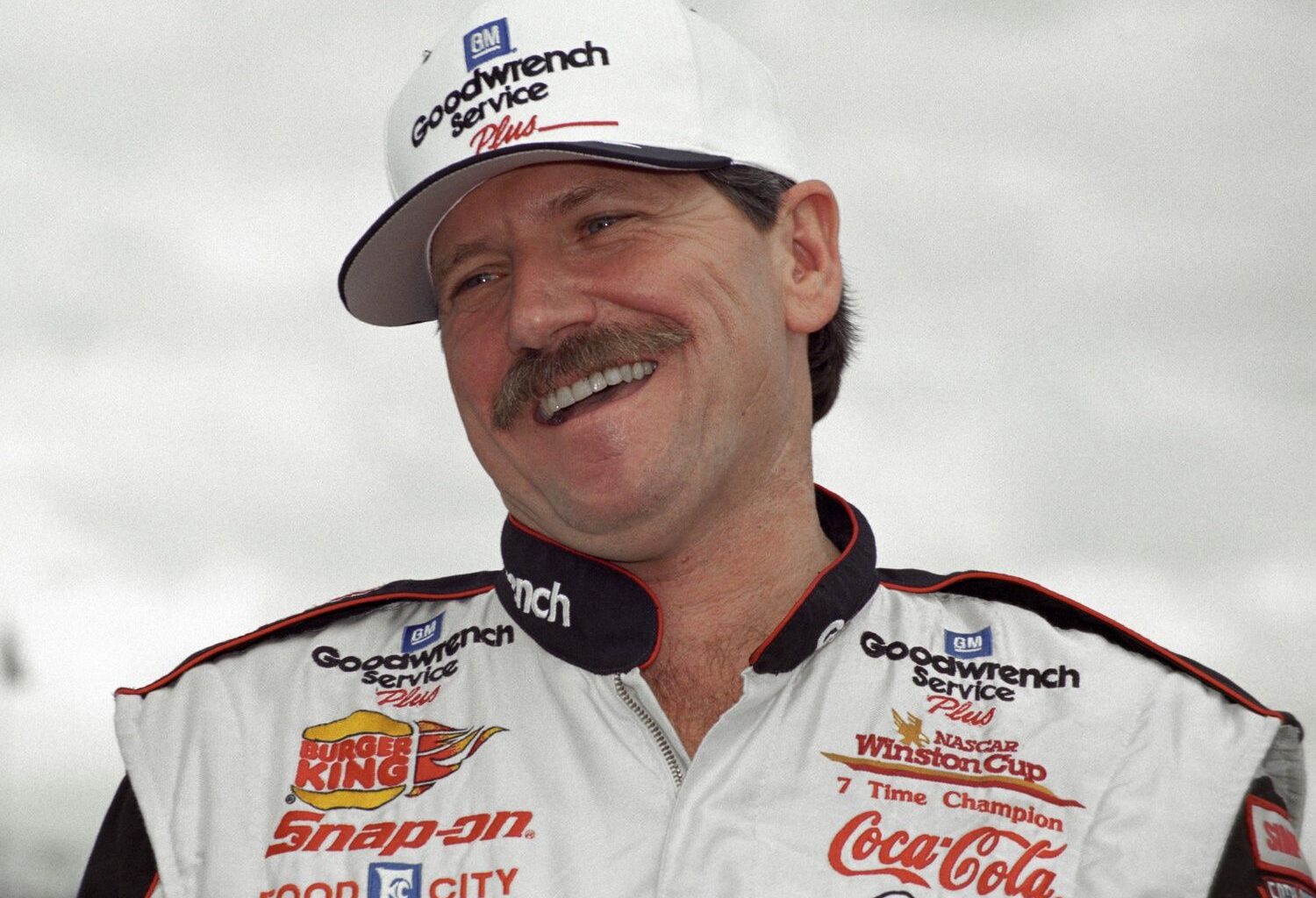

Dale Earnhardt Sr. had a unique way of breaking the ice with the new breed of professionals entering NASCAR’s garage area in the early 2000s. The seven-time champion’s playful nickname for his engineering crew offers a glimpse into how the sport was evolving during those transitional years.

What Did Dale Earnhardt Sr. Call His Engineering Crew?

Earnhardt used to call his engineering crew “train-drivers,” a light-hearted reference that revealed both his humor and the changing landscape of NASCAR. The nickname came to light through a conversation between motorsport content creator Bozi Tatarevic and ex-NASCAR engineer T Chris Andrews, who worked with Earnhardt at Richard Childress Racing.

Andrews said while cracking a laugh, “Dale Earnhardt called us all train drivers. In the early 2000s, engineers were pretty new on the scene in NASCAR, and we were all affectionately called train drivers cause that’s what they knew most engineers did more than anything.”

Dale Earnhardt called him “train driver” and today I learned why and asked my engineer Chris (@tcaellc) to share that story along with an experience of working with Dale at Sonoma as one of the earliest engineers in NASCAR.

Part 1: pic.twitter.com/FMd0bbk31p

— Bozi Tatarevic (@BoziTatarevic) July 12, 2025

The nickname perfectly captured the era when NASCAR was transitioning from its grassroots origins to a more technical sport. Engineers were slowly making their way into the garage, clipboards in hand, looking somewhat out of place among the grease-stained veterans who had built the sport’s foundation.

How Did Andrews First Work With Earnhardt at Sonoma?

Andrews shared the story of his first weekend working with Earnhardt’s team at Sonoma Raceway in 2000. The engineer had joined RCR at the end of 1999, bringing experience from Trans Am Racing to the NASCAR world.

“I was new at RCR at the end of 99. I didn’t travel with teams in 2000, but right before Sonoma, Kevin Hamlin, crew chief, asked me if I could go to Sonoma and help out because I had come from Trans Am Racing to NASCAR,” he said.

Hamlin recognized Andrews’ road racing background could prove valuable at the challenging California road course. “And he said, well, you might know more about road racing than I do, that was my first trip to the track with three car with Sonoma in 2000.”

The assignment Andrews received showed how different NASCAR operations were in those days. “I got there excited to be there first weekend at a Winston Cup Race, and Kevin handed me the radio and he said, go out to turn seven and spot. Don’t say anything on the radio unless you see somebody crash.”

“That’s what I did, I went out to turn seven, I stood out there like in the weeds up to my waist, watched the whole first practice. Listened on the radio and followed along.”

By Friday night, the team was struggling with their setup. Hamlin turned to Andrews for advice about their poor qualifying performance. “So, Friday night, Kevin Hamlin called me. We got together and he said man, what do you think we should do? We’re terrible, we’re awful, we qualified terrible, and I said, well, I ran a truck here year before we ran well with the truck at Sonoma.”

Andrews suggested several technical changes based on his road racing experience. “I think we need a bigger rear sway bar. I think we need softer rear springs. I think maybe we should try this with the front sway bar, shock adjustment. He was like Oh man, I don’t know. Dale doesn’t like rear sway bars. That’s poof, I don’t know.”

The story illustrates both the collaborative spirit of early NASCAR engineering and Earnhardt‘s particular preferences when it came to car setup. It also shows how the sport was beginning to embrace technical expertise while still maintaining the personal relationships and informal communication style that defined NASCAR’s culture.