This article is part of our NHL Arena Rankings series, in which we rank all 32 current rinks and present stories about memorable rinks of the past and present.

Once Rob Ray realized what was happening, the puck was three feet from his face.

The Buffalo Sabres enforcer-turned-analyst was working between the teams’ benches at the KeyBank Center, as a New York Rangers defenseman inadvertently launched a stretch pass out of play toward Ray’s grill during a February 2025 game. The smack — and ensuing reaction — was so loud, it picked up on Ray’s mic.

“Ah, f—.”

This season marks two decades of what might be the most hazardous TV job in sports: the between-the-benches color commentator. Amid flying snow, pucks and insults, these broadcasters are in the middle of the action while standing in an ice-level alcove sandwiched between two team benches. It makes for good TV — and has led to some legendary stories as analysts spin yarns about close calls with pucks and sticks, having front-row seats to on-ice scrums and of chirps and expletives lobbed over their heads.

“Being between the benches to do our job is the greatest place possible,” Ray told The Athletic. “From being a player, you get into the game a lot more. You get a better feel for it. You hear a little bit of what’s going on both sides. And you stay into the game.”

“It’s the greatest seat in the house,” TVA Sports reporter Renaud Lavoie said. “(The game) is really, really quick. You see everything. And that’s the beauty of it.”

“You’re right in the middle of the field of play,” former NBC and TSN hockey analyst Pierre McGuire said. “You’re basically an interloper in the players’ and the coaches’ office.”

NBC first introduced the concept of on-air talent working rinkside during the 2005-06 season, when reporters and analysts were “Inside the Glass,” as coined by NBC Sports producer Sam Flood. The idea was inspired by NASCAR pit reporters working alongside pit road and overhearing teams strategize during races.

“The concept was to put someone in real time who had played the game or coached the game, who could understand the code of the game of hockey, and give you real-time information about what’s transpiring on both teams’ benches,” Flood said.

However, it took time for the NHL to get on board with the idea. Flash back to mere moments before Game 5 of the 2004 Stanley Cup Final in Tampa, featuring the Lightning and Calgary Flames, when Flood sought out McGuire, then with TSN, for a quick question.

Flood grew up in Dedham, Mass., learning to play hockey as soon as he could walk and idolizing Bobby Orr of the nearby Boston Bruins. Flood played hockey in high school with his father, Richard, as his coach. Eventually, the younger Flood captained the Williams College hockey team. Years after graduating with a bachelor’s degree in history, Flood joined NBC as a researcher before progressing to producing live events, including in NASCAR.

When Flood wasn’t producing, he was back home in Boston helping his father with his summer hockey program. McGuire, armed with NHL coaching experience in Pittsburgh and Hartford, was among the program’s coaches.

So, Flood was more than familiar with McGuire’s work as an analyst and wondered aloud what he’d think about having someone call a game from between the benches. It would be a groundbreaking way for NBC to return to NHL coverage after striking a new broadcast deal with the league in May 2004, which kicked in for 2005 after a season-long lockout ended.

Pierre McGuire, once an analyst for NBC Sports, watches a game from between the benches in 2014. (Brace Hemmelgarn / USA Today)

“I know I could, but there’s no way the league will ever allow that,” McGuire told Flood. “(Flood’s) exact phrase to me was, you leave that to (NBC Sports President) Dick Ebersol and myself, and we’ll get it done. If you think you can do it, you’ve got the job.”

Flood initially met with league broadcast executives who weren’t sure how NHL arenas would make space for on-air talent to hang around near the ice, and ultimately shut down his idea. Undeterred, Flood presented his idea to NHL commissioner Gary Bettman during a post-lockout meeting and tried to sell him on “Inside The Glass” being a “unique way that could potentially change the way hockey is covered.”

“And Gary said, ‘Well, that sounds like a great idea, Sam. We’ll make sure it happens,” Flood said.

NBC started coverage in time for the 2005-06 season, with some teams allowing reporters on their bench. But pushback continued from some teams, including the Anaheim Ducks, whose arena didn’t have sufficient space for on-air talent. In the hopes of changing his mind, four hours before a Stanley Cup Final game in 2007, Flood met with then-Ducks GM Brian Burke in his office as he rode an exercise bike.

During a December 2004 meeting, in the midst of the season-long NHL lockout, the two clashed during a meeting led by Brendan Shanahan — dubbed the “Shanahan Summit” — in which a handful of players, coaches, and executives discussed how the game could improve. When Flood complained that the NBA provided more media access to its players compared to the NHL, Burke said, “There’s no f—ing way we’ll let that happen.”

Two and a half years later, Flood stood in front of the exercising Burke and pleaded for a space along the bench for McGuire to broadcast the game. Burke wasn’t happy. Flood didn’t want to “pull rank” and have the NHL call Burke to tell him to make room. But he would if necessary. Burke bluntly told him to get the “f—” out of his office.

“Go ahead and call Bettman if you have to. I’m not agreeing with it,” Burke said. “Bettman called me and said, ‘Yes, you are.’ I argued with Gary, too, but didn’t have any force. So, Pierre was on our players’ bench during a game.”

“Burke and I had mutual respect,” Flood said. “He wanted what was best for the NHL, and I think he trusted (it). Because he’d seen two seasons at this point of the on-the-bench concept, and it was very well received and people wanted to use it.”

Twenty years after Flood’s “Inside the Glass” concept began, having reporters and analysts alongside benches has become the norm for fans and coaches. Broadcasters such as TNT will even have three-person broadcasts featuring a play-by-play and color commentator in the booth, while a reporter/analyst will occupy their in-between-bench role.

“I’m trying to gather stuff that’s going on at ice level,” TNT broadcaster and former goaltender Brian Boucher said. “Maybe the temperature of the game, something I’m hearing at ice level. So, you get in two different perspectives when we do that broadcast.”

With that access, sometimes the action gets a little too close.

Former NHL backup goaltender Jamie McLennan suffered two concussions over a 17-year pro career, 11 of those in the NHL. McLennan, now a TSN broadcaster, has had the same number of concussions in the last three years working between the benches as an analyst. Both came from sticks that whacked him in the head. Both came from defensemen, Erik Brannstrom and Mark Borowiecki, reacting after being hit along the boards.

“I always joke that, knock on wood,” McLennan added, pun unintended. “The next time I get hit will be the last time, because I’m going upstairs for good.”

Analysts and reporters such as McLennan have similar stories. They’ve experienced close calls with pucks and sticks while having front-row seats for on-ice scrums and angered coaches, eavesdropping on chirps they wouldn’t normally hear. Such as the time Lavoie heard a back-and-forth between former Montreal Canadiens and Ottawa Senators captains — and eventual future teammates — Max Pacioretty and Mark Stone.

“Stone was looking at Pacioretty,” Lavoie remembered. “And he was like, ‘No one likes you on your team. Everyone hates you on your team.’ And (Pacioretty) was the captain. And (Pacioretty) was like, ‘No, that’s not true. Everyone loves me.’ And Stone was like, ‘No, they all hate you.’”

Or when former NWHL star and ESPN and Amazon Prime Hockey analyst Blake Bolden got “smoked” on her cheekbone by the heel of a stick blade as a player came off the ice for a line change.

“I remember freaking out a little bit inside, because I’m on air. I know I’m live,” Bolden said. “I think I pulled it off so nicely, and I didn’t look like I was rattled. Even though I was, because it was throbbing. I kid you not. It hurt so bad.”

And even innocuous fun can prove troublesome, as Seattle Kraken analyst and former NHLer JT Brown explained after his former teammate Yanni Gourde skated toward him and snowed him after a hard stop.

“Not only did he get me,” Brown said. “But more importantly, he got my notes. And I was using just a regular pen, regular paper.

“It was gone. Everything. So, all my notes for the game, gone,” he added, remembering Gourde laughing in his face as he showed him his drenched notes.

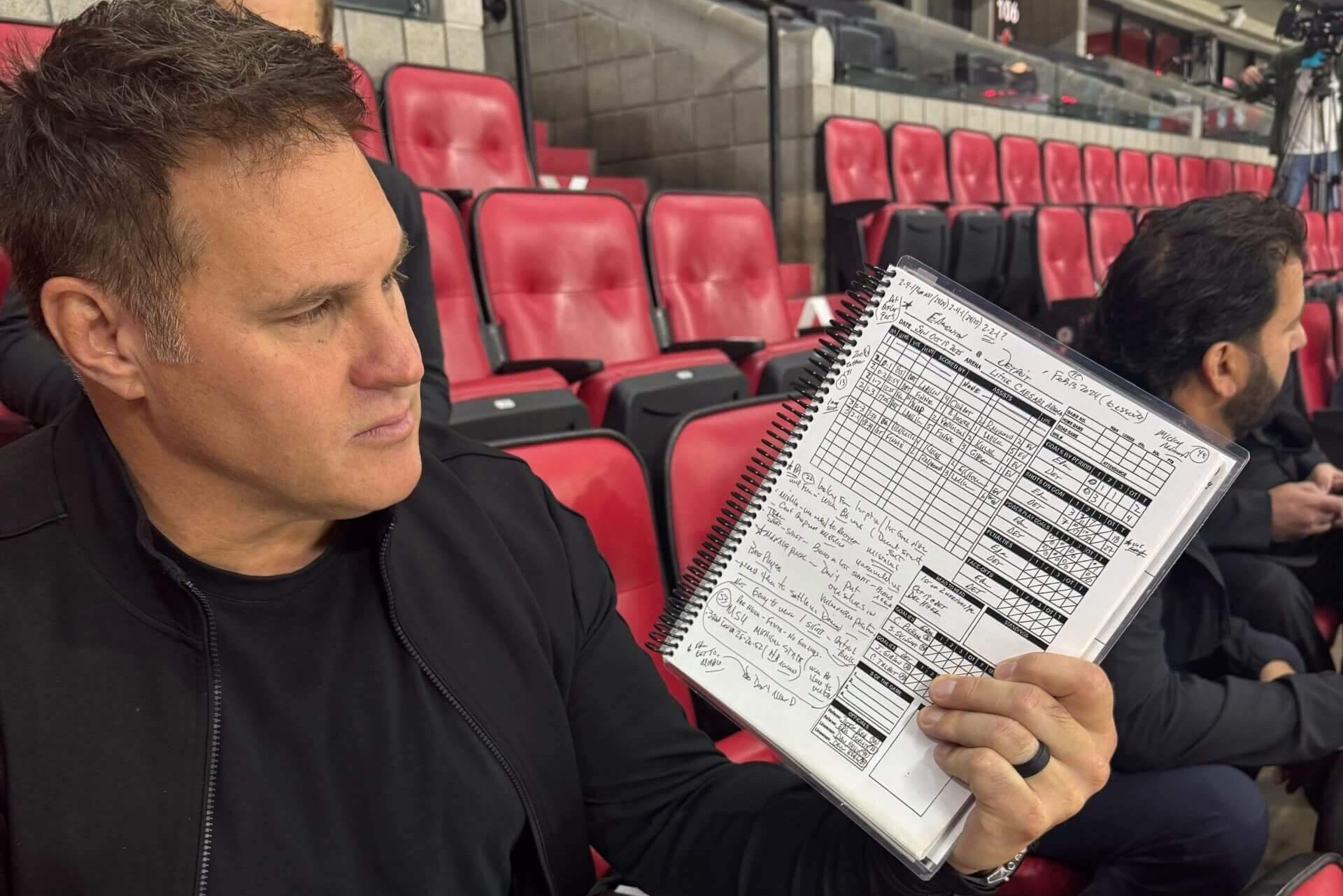

In response, Brown now exclusively writes his notes on 80-lb cardstock notebooks and with thin-point Sharpies.

“So that if it does get wet, it doesn’t ruin my whole notes,” Brown said.

Sportsnet broadcaster Louie DeBrusk’s notes are in a notebook covered in hard plastic, which can help avoid the same fate that Brown once suffered, among other hazards. During one of his first games between the benches, he shared the space with fellow broadcaster and former NHL goalie Darren Pang, who likened his notebook to a goalie “blocker,” which can prove useful to DeBrusk for oncoming pucks shot in his direction.

“If I think the puck’s coming,” DeBrusk said, holding up his notebook. “I’m just blocking my face.”

Louie DeBrusk shows his game notes. (Julian McKenzie / The Athletic)

But if you think brushes with pucks, sticks and players should entice on-air talent to wear protective gear such as a helmet while rinkside, there will be detractors. It’s something many broadcasters, such as Lavoie, hope never happens.

“If you look at the number of games that were played with people between the benches in the last 10, 12, 15 years, there’s not a lot of major incidents,” Lavoie said. “It’s happened. It’s always going to happen.

“I think that if you’re really cautious, if you’re dialed in, if you watch the game, if your eyes are always on the puck, you’re never going to get hurt.”

After taking that puck to the face last February, Ray called the game with a golf-ball-sized welt on his face, inches above his left eye. The last time he got hit by a puck, it was right in between his eyes and he needed up to eight stitches. This time around, he made light of the situation. Days later, he called part of the next Sabres broadcast from the arena nosebleeds and even wore a helmet.

He will not require said helmet for future broadcasts. Despite the risks and pain, Ray loves his job working games in between the benches — arguably one of the most unique jobs in the sports broadcasting world — and wouldn’t change a thing.

“If I could do all 82 games between the benches, I’d do it in a second,” Ray said. “Getting hit, whatever, I don’t care. Because it’s so much more enjoyable being down there than being up top.”

The NHL Arena Rankings series is part of a partnership with StubHub. The Athletic maintains full editorial independence. Partners have no control over or input into the reporting or editing process and do not review stories before publication.