Version originale en français, Carte commentée. Le Groenland dans le viseur de Trump : menace chinoise ou course aux minéraux critiques ?

JANUARY 2026. Donald Trump reiterates his desire to acquire Greenland, presenting it as a “national security priority” in response to what he describes as the Chinese threat in the Arctic. The proposal, which had already sparked controversy during his first term in 2019, now returns with greater rhetorical intensity and in a changed geopolitical context. But does this ambition truly respond to defence imperatives, or does it conceal strategic objectives of another kind ?

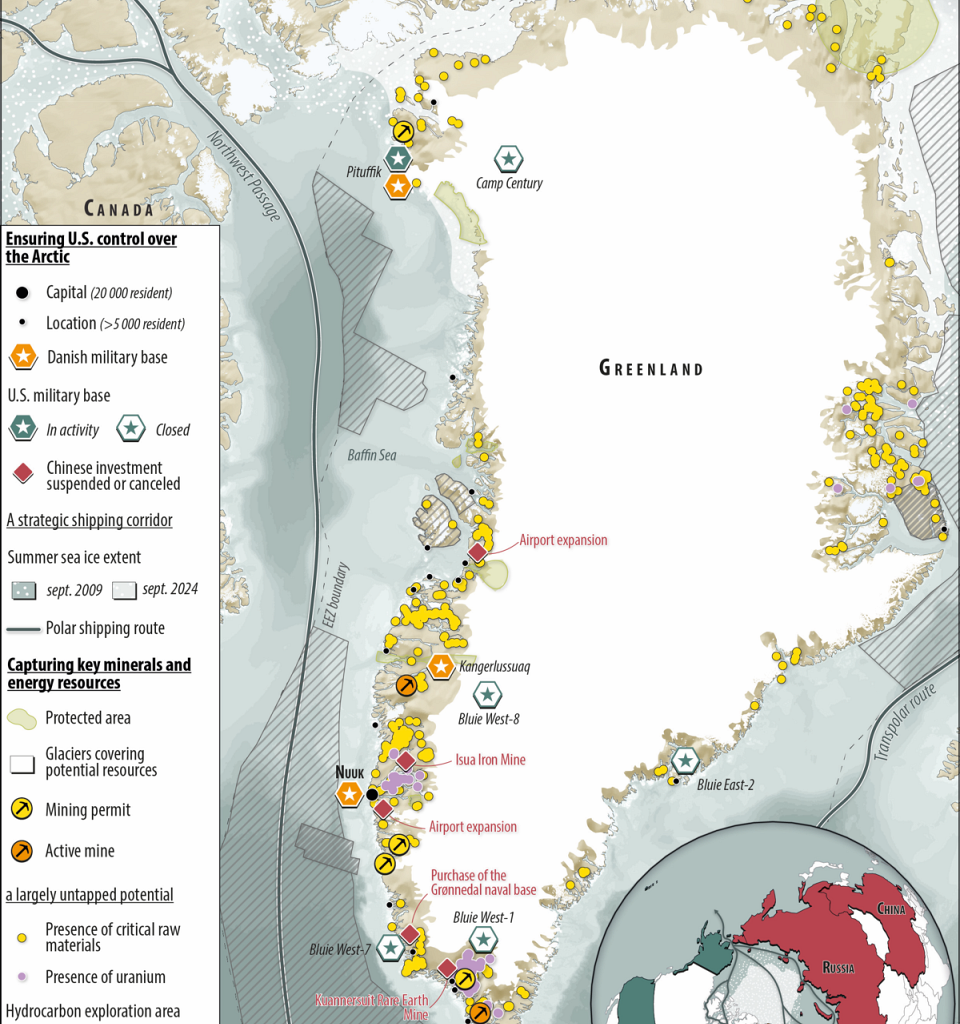

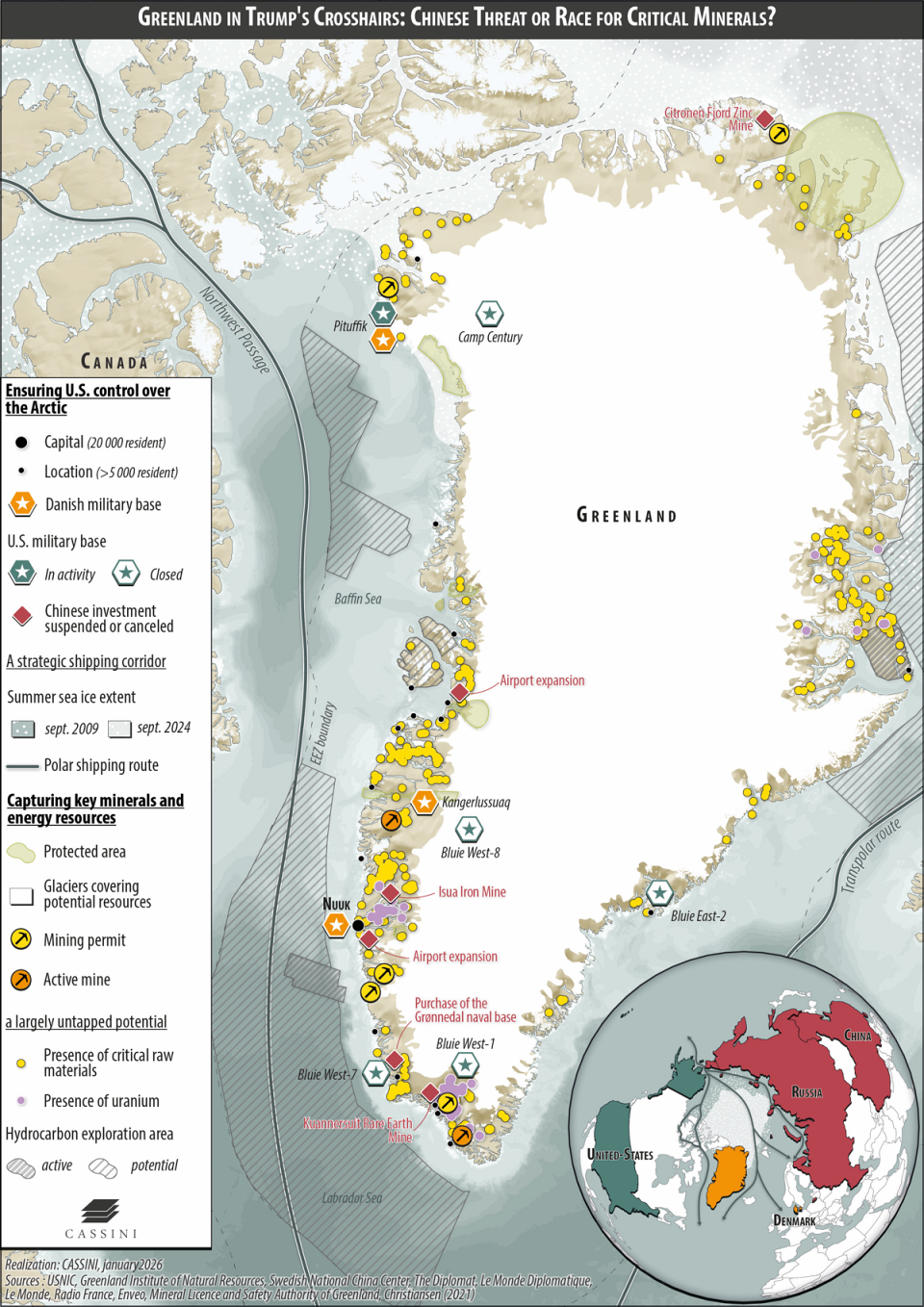

Map. Greenland in Trump’s Crosshairs : Chinese Threat or Race for Critical Minerals ?

In Greenland, it is for Washington to ensure US control over the Arctic and to get its hands on mining and energy resources. Map in PDF format for high-quality printing. Design and production : Cassini, January 2026.

A cartographic analysis allows us to break down the various factors converging in this renewed American interest. The world’s largest island, with a surface area of 2.16 million km²—81% of which remains covered by ice – has a population of barely 56,000, concentrated in coastal settlements with no land connections between them. Despite this apparent marginality, the Trump administration’s motivations are not limited to containing China ; they also involve global competition for critical mineral resources, opportunities created by climate change, and the reconfiguration of Arctic trade routes. Understanding the complexity of this geographic space requires looking beyond official rhetoric.

The Security Argument : A Limited Chinese Presence

The White House justifies its interest in Greenland by citing the need to counter what it describes as growing Chinese influence in the Arctic. It is true that the Chinese government, which in 2018 declared itself a “near-Arctic state,” has increased its capabilities in the region through the construction of icebreakers and the promotion of a “Polar Silk Road.” However, China has only three icebreakers, compared to the fleet of more than forty operated by Russia, and China’s physical presence in Greenland is considerably more modest than the White House suggests.

Successive Chinese investment attempts in Greenland have been systematically blocked by the Danish government or have failed for economic reasons.

Chinese efforts to establish an economic foothold on the island have faced recurring obstacles. In 2018, when China Communications Construction Company bid to finance the expansion of the Nuuk and Ilulissat airports, the Danish government intervened directly to take over the project, thus preventing Chinese control over infrastructure deemed critical. A similar pattern emerged in 2016, when the Hong Kong-based company General Nice attempted to acquire a decommissioned Danish naval base at Grønnedal. At that time, the Danish government blocked the transaction, citing national security reasons.

Other extractive projects with Chinese participation have met various fates, but none has materialised. A licence to develop the Isua iron mine, acquired by General Nice in 2015, was revoked by the Greenlandic government in 2021 after years of inactivity and non-payment. The Citronen Fjord zinc project, in which NFC (China Nonferrous Metal Industry) signed a memorandum of understanding in 2014, lost momentum and its promoters eventually turned to American investors. As for the Kuannersuit rare earth deposit in the south of the island, the 2021 reinstatement of the uranium extraction ban, which applies to uranium present alongside the rare earths, has effectively paralysed the project, despite the participation of Chinese group Shenghe Resources as a shareholder. The parent company, Energy Transition Minerals, is currently seeking $11.5 billion in compensation through international arbitration.

This record of failed attempts significantly nuances the narrative of a Chinese “omnipresence” threatening American security. The urgency invoked by the Trump administration also contrasts with the established position that the United States already maintains on the island. Pituffik Air Base, formerly known as Thule, is the northernmost American military installation and has operated continuously since the Cold War. Its early warning radar forms part of North America’s missile defence system. The United States has agreements with the Danish government that would allow it to expand this presence if deemed necessary.

A Climate Opportunity

Interest in Greenland cannot be separated from the transformations that climate change is bringing to the Arctic. The accelerated retreat of the Greenlandic ice sheet is creating opportunities that seemed unthinkable decades ago. Between 1979 and 2024, the extent of summer sea ice has been reduced to approximately half the levels recorded in the 1980s, opening up coastal zones and facilitating access to previously inaccessible territories.

This development has direct consequences for natural resources. Vast areas of Greenland, currently covered by glaciers, contain mineral deposits whose exploitation was previously technically and economically unfeasible. As the ice retreats, these reserves are becoming progressively accessible. At the same time, the reduction of sea ice is expanding the navigability window of Arctic corridors, such as the Canadian Northwest Passage, which can save up to two weeks compared to the Panama route, or the Siberian Northern Sea Route, which halves the journey between Asia and Europe.

For the United States, controlling Greenland is equivalent to securing a privileged position over resources and trade routes whose importance will only grow.

In this context, controlling Greenland takes on a forward-looking dimension. It is not only about the present situation, but about anticipating a scenario in which the Arctic becomes a space for commercial transit and resource extraction comparable to other strategic regions of the planet. The United States lacks significant Arctic coastline beyond Alaska, while Russia holds more than half of the Arctic littoral and Canada another quarter. Arctic routes still operate with limited navigation windows, but climate models project essentially ice-free summers before mid-century. Greenland, with its more than 44,000 kilometres of coastline, would offer the United States a privileged gateway to this new arena of global competition.

The Mineral Imperative : The Real Race

While the security argument requires nuance and the climate factor operates over the medium term, there is a more immediate motivation that more precisely explains American insistence : access to critical minerals. Greenland contains 25 of the 34 minerals that the European Union has classified as critical for the energy and technological transition, including rare earths, graphite, cobalt, and copper. Its rare earth reserves, estimated at 1.5 million metric tonnes, are comparable to those of the United States and greater than Canada’s. Deposits such as Kvanefjeld concentrate neodymium, dysprosium, and terbium, elements essential for manufacturing high-power magnets.

This geological wealth assumes strategic relevance when considering current market structures. China controls approximately 90% of global rare earth refining capacity – elements indispensable for manufacturing wind turbines, electric vehicles, military guidance systems, and virtually all advanced electronic devices. The Chinese government has used this dominant position as a foreign policy tool, imposing export quotas that affect Western supply chains. In 2010, during a territorial dispute with Japan, it temporarily restricted rare earth exports, triggering a price surge that exposed the vulnerability of dependent economies.

The United States has directly experienced this vulnerability. Dependence on Chinese imports for essential components of its defence and technology industries represents a structural weakness that successive administrations have attempted to address. Efforts to develop domestic extractive capabilities – such as the Mountain Pass mines in California, Vulcan Elements projects, or ReElement Technologies recycling facilities – are steps in that direction, but remain insufficient to alter the situation in the short term.

Integrating Greenland into the American economic sphere would offer a more direct solution. Greenlandic reserves, if exploited at significant scale, would provide the United States with its own supply source, reducing exposure to Chinese restrictions and strengthening its strategic autonomy in key sectors. This logic fits into a broader trend in recent foreign policy, also evident in the mining agreements signed with Ukraine after the Russian invasion, aimed at securing access to critical raw materials through bilateral alliances.

However, the gap between reserves and effective exploitation is considerable. Greenland lacks roads between its settlements, has limited port infrastructure, and currently operates only two mines in its entire territory, dedicated to extracting gold and anorthosite for thermal insulation. Political risk, following the revocation of licences such as Kuannersuit, has undermined investor confidence. Analysts estimate a horizon of ten to fifteen years and an investment of billions of dollars before any rare earth project reaches the production phase. Even then, the extracted ore would have to be sent to China for processing, given the Chinese monopoly on refining capabilities.

European Dilemmas in Arctic Rivalry

The Trump administration’s focus on Greenland reveals a significant gap between official discourse and underlying motivations. The rhetoric of a Chinese threat serves a legitimising function, providing a comprehensible narrative for public opinion. However, China’s actual presence in Greenland, as we have seen, is limited ; what truly concerns the American government is Chinese dominance over critical mineral value chains, not its establishment on the island.

The debate over Greenland illustrates how competition for natural resources is reconfiguring the geopolitical priorities of great powers. Climate change acts as a catalyst, transforming a peripheral territory into an area of growing strategic relevance. Critical minerals form the material core of this interest. Without them, the Western energy transition remains subject to decisions made by the Chinese government.

For the Danish and Greenlandic autonomous governments, this convergence of pressures presents considerable dilemmas. Approximately 50% of Greenland’s economy depends on Danish subsidies (about 600 million dollars per year), and exports from the fishing sector account for nearly one-quarter of its GDP. The relationship with the United States is a central element of Danish security architecture, but proposals for territorial acquisition conflict both with Greenlandic self-determination rights and with the Danish government’s sensitivity to interference in its sovereign space. The debate over Greenland’s future status (which already has an autonomous executive with broad powers) is likely to intensify in the coming years.

For the European Union, the case presents an additional dilemma. Denmark is a member state ; Greenland, although outside the EU since 1985, maintains association agreements with European institutions. Sustained pressure from the American administration on this territory would force the European Council to define a collective position, exposing divergences between more Atlanticist governments and those advocating greater strategic autonomy. If member states were unable to articulate a common response to pressures on the sovereign space of one of them, the very viability of an integration project aspiring to be a geopolitical actor would be called into question.

The Greenlandic case clearly illustrates the centrality that natural resources, particularly critical minerals, have acquired in contemporary geopolitical competition. The energy transition, far from depoliticising access to raw materials, is generating new forms of dependence and rivalry. In this context, territories once considered peripheral acquire unexpected relevance. Greenland is now one of those spaces where competition for critical resources becomes territorialised, and where the outcome will depend as much on the decisions of great powers as on the capacity of local actors to defend their own priorities.

Copyright Janvier 2026-Cattin-Palacios/Cassini-Conseil/Diploweb.com

Map in PDF format for high-quality printing.

Map. Greenland in Trump’s Crosshairs : Chinese Threat or Race for Critical Minerals ?

Realization : Cassini, january 2026

Version originale en français, Carte commentée. Le Groenland dans le viseur de Trump : menace chinoise ou course aux minéraux critiques ?