Kaiser Permanente study finds medication is still necessary for patients with a reduced ejection fraction that improves over time

Several medications used to treat heart failure with a reduced ejection fraction have been so effective that cardiologists have had to establish a new category: heart failure with an improved ejection fraction. But as a large new study led by Kaiser Permanente researchers shows, patients with an improved heart function still need treatment.

“We found that nearly 1 in 3 of our patients saw their ejection fraction improve in the first year of being on these medications,” said senior author Ankeet Bhatt, MD, MBA, ScM, a research scientist at the Kaiser Permanente Division of Research and a cardiologist with The Permanente Medical Group. “But as our study showed, although their heart function has improved, these patients are still at high risk for worsening heart failure, and they still need treatment.”

Ejection fraction is a measure of how much blood the heart pumps out from its left ventricle with each beat. A normal ejection fraction is typically between 55% to 60%. When the measure is 40% or less and a patient has heart failure-related symptoms, the diagnosis is heart failure with a reduced ejection fraction. If after starting treatment, the patient’s ejection fraction increases by at least 10% to over 40%, the diagnosis is heart failure with improved ejection fraction. The new study published n the Journal of the American College of Cardiology is believed to be the largest and most contemporary assessment in the U.S. of patients who see this improvement.

. . . although their heart function has improved, these patients are still at high risk for worsening heart failure, and they still need treatment.

— Ankeet Bhatt, MD, MBA, ScD

The research included 28,292 members of Kaiser Permanente Northern California (KPNC) who were newly diagnosed with heart failure with a reduced ejection fraction between 2013 and 2022. Within this group, the investigators identified 8,656 patients (30.6%) who started treatment and met the criteria for heart failure with improved ejection fraction within 12 months of their diagnosis. These patients had a 40% reduction in the risk of worsening heart failure or death. Specifically, the study found 17 cases of worsening heart failure and 6 deaths per 100 person years among the patients with an improved ejection fraction compared to 34 cases of worsening heart failure and 11 deaths per 100 person years among the patients whose ejection fraction did not improve.

“Seeing these better outcomes and being able to tell patients on treatment whose ejection fraction improves that they are less likely to develop worsening heart failure or to die from heart failure is important,” said first author Kyung H. Min, MD, a KPNC resident physician.

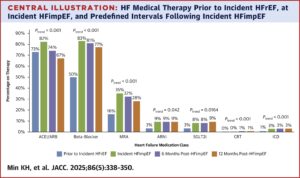

All the patients in the study had been prescribed similar treatments when they were initially diagnosed with heart failure. However, patients who were started on additional evidence-based medications were more likely to see their ejection fraction improve. The researchers also found that, over time, use of potentially life-saving medication decreased in the patients with improved ejection fraction, and those who stopped taking their medications altogether were more likely to develop worsening heart failure.

“Even though these patients see their ejection fraction improve, they need to know that their risk of worsening heart failure is still likely substantially higher than it would be for someone who never had heart failure, and that they need to stay on their medication,” said Min. “Improving their ejection fraction does not seem to cure their heart failure syndrome.”

Treatment guidelines

In 2022, the American College of Cardiology and the American Heart Association incorporated the new category of heart failure with an improved ejection fraction into treatment guidelines. These guidelines recommend that patients stay on medications approved to treat heart failure after their ejection fraction improves.

“There are multiple components to heart failure medical therapy,” said Bhatt. “Our findings support our current understanding that optimal and timely treatment of heart failure with a reduced ejection fraction can increase the likelihood of heart function improvement. They also suggest that maintaining these treatments even after heart function improves may continue to be beneficial.”

“There are multiple components to heart failure medical therapy,” said Bhatt. “Our findings support our current understanding that optimal and timely treatment of heart failure with a reduced ejection fraction can increase the likelihood of heart function improvement. They also suggest that maintaining these treatments even after heart function improves may continue to be beneficial.”

Bhatt said there might be some patients with an improved ejection fraction who can stop treatment, but more research will be needed to identify that group. “We saw that more than 20% of patients who had an improved ejection fraction experienced worsening heart failure or died over the following 3 years,” said Bhatt. “This suggests that the heart is still weakened or vulnerable, and until we know more about the patients with improved ejection fraction, we would not suggest anyone stop their medications, especially without first speaking with their doctor.”

Funding for this study was provided by Kaiser Permanente Northern California.

Co-authors include Alan S. Go, MD, Rishi V. Parikh, MPH, Kate M. Horiuchi, Andrew P. Ambrosy, MD, and Thida C. Tan, MPH, of the Division of Research; Keane Lee, MD, Jana Svetlichnaya, MD, Ivy A. Ku, MD, and Sirtaz Adatya, MD, of The Permanente Medical Group; Kishan Srikanth, MD, and Steven A. Hamilton, MD, of Kaiser Permanente Northern California; Scott D. Solomon, MD, of Brigham and Women’s Hospital; Riccardo M. Inciardi, MD, of University of Brescia, Italy; Orly Vardeny, PharmD, MS, of the University of Minnesota; and Elena Vasti, MD, and Alexander T. Sandhu, MD, of Stanford University.

###

About the Kaiser Permanente Division of Research

The Kaiser Permanente Division of Research conducts, publishes, and disseminates epidemiologic and health services research to improve the health and medical care of Kaiser Permanente members and society at large. KPDOR seeks to understand the determinants of illness and well-being and to improve the quality and cost-effectiveness of health care. Currently, DOR’s 720-plus staff, including 73 research and staff scientists, are working on nearly 630 epidemiological and health services research projects. For more information, visit or follow us @KPDOR.