Taxpayers, get ready for another round of bailouts. But, unlike Wall Street executives who begged Uncle Sam to cover their risky bets, cash-strapped nonprofit rural healthcare providers have not gambled away their resources.

Quite the contrary, they have done nothing irresponsible. The best part is the bailout is not a fait accompli. The solution is simple: Louisiana’s lawmakers, and other state legislatures, can codify access to the critical savings that providers attain under the 340B Drug Pricing Program.

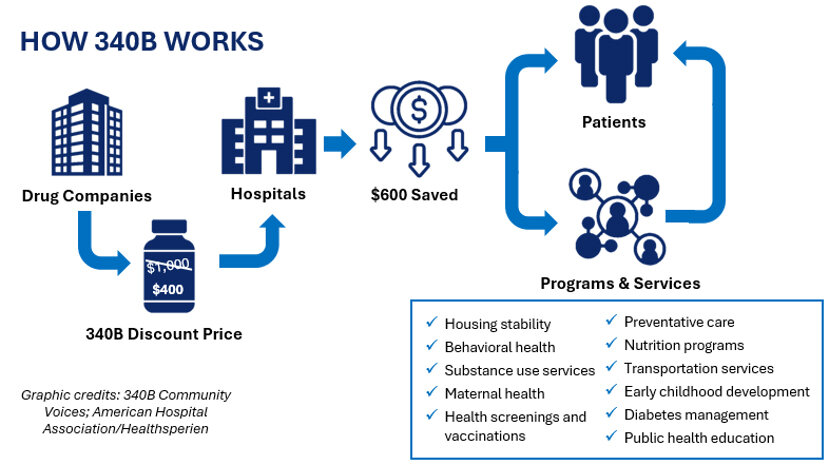

Through no fault of their own, rural hospitals and clinics find their operating expenditures squeezed by the public and private sectors. On the public end, the federal government reimburses care below cost for people on Medicaid, a significant portion of the patient mix for nonprofit providers that care for the working poor. These nonprofit providers deliver high-quality medical services they know will put them in the red. And they are fine with that, because they have a healthcare mission, not a remit for generating revenue.

On the other side, drug companies are harming providers by undermining 340B, a lifeline for Louisiana’s safety net providers. Drug companies began their assault on 340B-eligible providers in 2020 by restricting where providers can access their drug discount purchase savings.

The first year saw only a handful of drug companies shirking their 340B responsibilities. Fast forward to today, and almost 40 companies have restricted access to at least one of their products. In effect, drug makers are denying resources the law entitles to eligible healthcare nonprofits.

The resulting cash crunch forces providers to reduce services. Lack of resources means many will cease operations altogether, contributing to the healthcare desert crisis ravaging rural America.

Since 2010, 89 rural hospitals have closed, two of which were in Louisiana. Another 65 underwent “converted closures,” defined by reducing or eliminating services, changing locations, and/or closing facilities. According to a 2025 analysis from the Center for Healthcare Quality and Payment Reform, 760 rural hospitals are at risk of closing, with 40 percent facing an immediate risk of shutting down.

For Louisiana, 25 rural hospitals (45 percent) risk closure, with seven at immediate risk. Understand that the current financial reality occurred even with the critical savings enabled from 340B. The fundamental changes to the program desired by drug companies would cause catastrophic damage to healthcare in rural America.

Louisiana officials on both sides of the political aisle have acted to prevent further damage to their healthcare safety net. Former Governor Edwards signed Act 358 into law in August 2023, making Louisiana one of the first states to prohibit contract pharmacy restrictions by drug makers and discriminatory reimbursements by PBMs. The move paid immediate dividends, as some drug companies paused their contract pharmacy tactics. In 2024, a district court in Louisiana upheld the state law, siding against drug makers.

Drug companies do not care. Their lawfare will continue. For all their faux concern about just wanting to ensure patients benefit directly from 340B discounts, drug makers have one goal—to limit the number of prescriptions available at discounted prices. Fewer 340B prescriptions means more money. They do not care if they bankrupt rural providers and leave taxpayers to pick up the tab.

As multiple lawsuits are working their way through the judicial system, drug companies have adopted a new scheme to put the screws to 340B providers. Unsatisfied with using contract pharmacy restrictions to starve providers of resources in the short and medium term, they now want to convert the upfront savings providers rely on to rebates on the back-end of drug purchases. The maneuver, if green-lit by the federal government, would end 340B through provider attrition. And that is the long-term goal: Fundamental changes to 340B on the drug industry’s terms.

Here is what drug companies want: Delay. The plan is to reimburse providers at an indeterminate future date, on their own terms, making every 340B claim subject to dispute and protracted payment. Drug companies understand that many rural providers operate on shoestring budgets. If they can slow-walk how covered entities attain 340B savings, providers face resource deficits they cannot overcome.

What if drug makers deny every initial rebate claim, extending the life cycle of payments months down the road? The clinical outcomes of millions of rural Americans depend on their providers, often the sole provider they can access, receiving upfront 340B savings to keep their doors open.

Louisiana must continue its leadership in defending 340B at the state level. The attorney general should file suit against any company that institutes a rebate scheme. Lawmakers should write legislation that forbids a payment model that converts upfront discounts to rebates. If drug makers get their way, rural providers will have their hands out to the federal government, asking taxpayers to underwrite the consequences of the drug industry’s enrichment goals.

Louisiana should not leave providers at the mercy of national politics. Federal solutions take too long to materialize, if they happen at all. The time to act is now.

John Arcano is senior manager of policy and government affairs at AIDS Healthcare Foundation.