As a part of our 25th-anniversary celebration, we’re republishing formative magazine stories from before our website launched. This story previously appeared in Dwell’s February 2001 issue.

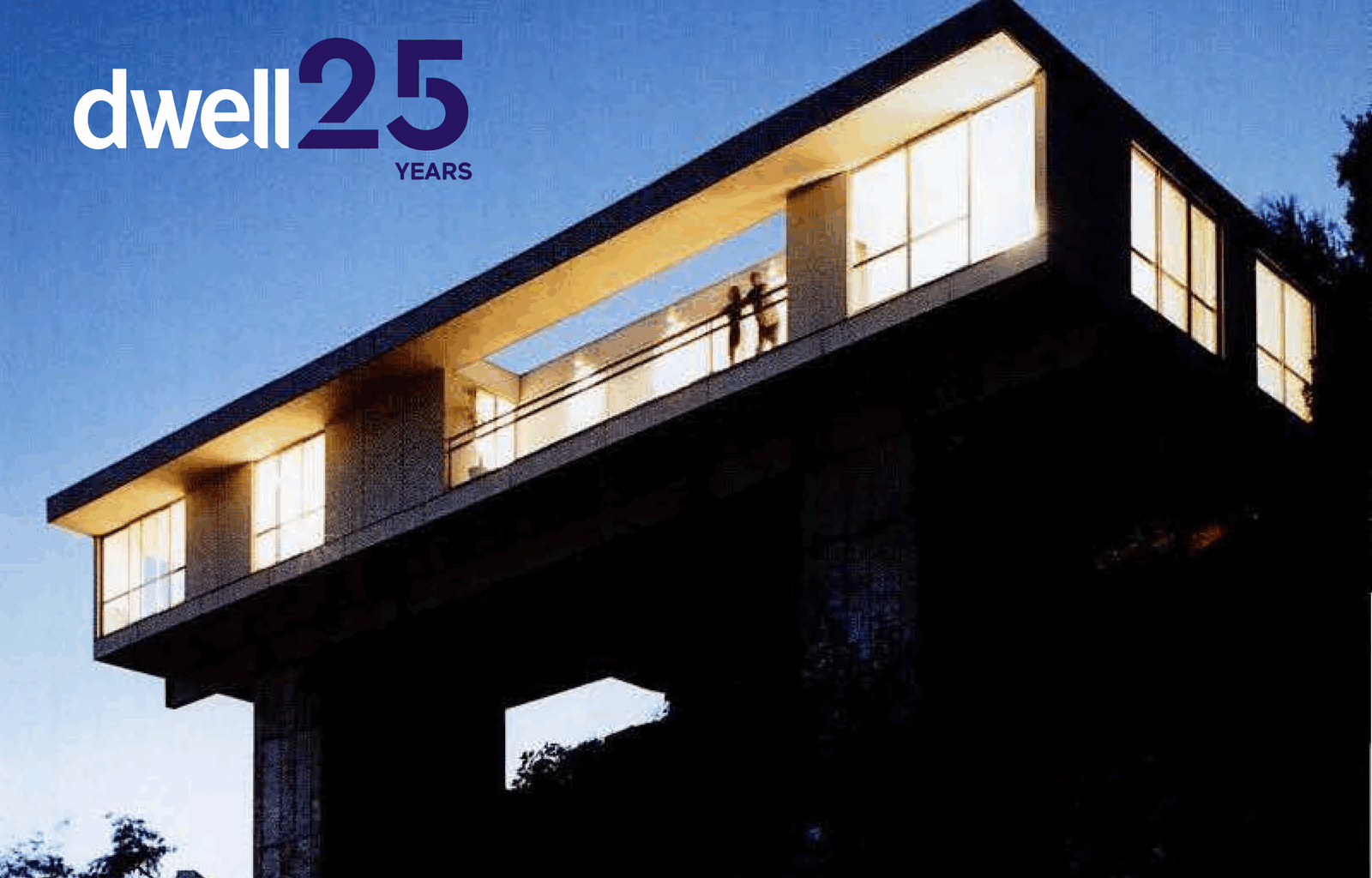

The very first people to be shocked by architects Frank Escher and Ravi GuneWardena’s supremely minimalist house, floating in space high above Pasadena, were the couple who commissioned it. Bryce Jaime, 35, had been dreaming about “a rustic, cabin-style house,” but his wife, Rochelle, a Montessori schoolteacher, persuaded him to go for something more up-to-date. Yet, even Rochelle, who admits to instructing the architects—”I wanted lots of air, lots of white, and I wanted it extremely modern”—was taken aback when she saw the plans for a futuristic box perched atop two massive towers.

Had the Jaimes known the two 40-year-old architects better, perhaps they wouldn’t have been surprised. Soft-spoken and cerebral, this pair’s highly rational ideas about architecture are unusual in Los Angeles, where artistic heroes such as Frank Gehry, who put a premium on the lyrical exteriors of their buildings, are routinely worshiped.

“We don’t design something because we think it’s fashionable. Not at all,” declares Escher, who, with pale complexion, unkempt black hair, and a utilitarian polo shirt, appears too intense for his thin frame.

Referring to their philosophy as “poetic rationalism,” Escher and GuneWardena favor geometric, structure-based design. They play around for hours with the volumes of an interior space—eliminating what they regard as nonfunctioning in-between spaces—before they even consider the outside of a building.

“This ensures that even the smallest of houses will seem expansive,” says GuneWardena, whose pinstriped shirttails tend to hang outside his pants and whose quick smile masks his seriousness. Partners in the office and at home, Escher and GuneWardena are both obsessed with cost-effectiveness; for instance, they persuaded the Jaimes to lower the ceiling height on their house so that patio doors and windows available at WindowMaster could be used.

Of course, Bryce Jaime, a senior networking engineer at Paramount Pictures, didn’t know any of this when, in 1996, he telephoned the pair for advice. All he remembered was that 11 years earlier, GuneWardena, born in Sri Lanka (as were both the Jaimes), had designed a house for his uncle in San Diego.

Jaime had seen a steep hillside lot in Pasadena for sale, one that fulfilled his primary requirement: “I always wanted to look out over a golf course.” Jaime hoped that, like a surfer who spends hours surveying the ocean, he could improve his golf game by gazing out, day after day, at 18-hole links. Actually, standing on the road above their future home site, he and Rochelle couldn’t see much besides the Brookside Golf Course. The site plunged so precipitously from the pavement that Jaime asked himself, “Could you even build here?” In desperation, he reached out to GuneWardena.

The client’s love of golf should have been a tip-off for the less athletically inclined architects that their highly evolved ideas about design might not be immediately understood, let alone embraced. The Jaimes, who had come from Sri Lanka in the late 1980s in pursuit of a better life, proved to have highly conventional ideas about the house that would fulfill that goal. They wanted, all separate and enclosed, a formal dining room, four bedrooms, a family room, and, of course, a powder room by the front door. By contrast, the architects’ conception involved “simply one big space with some wall partitions.”

“But,” says GuneWardena, “we had to acknowledge that was how we would like to live, and even if we’d convinced them to live ‘our way,’ they would have gone back to the way they were used to living.”

Escher and GuneWardena decided the best way to nudge the Jaimes into their way of thinking was to give them a quick lesson in Los Angeles modernism. The subsequent tour included a visit to the Chemosphere House, a flying saucer-like home designed by John Lautner in 1960. Also on a steep hillside, and owned by the German publisher Benedikt Taschen, the Chemosphere is being restored under the guidance of GuneWardena and Escher, who administers the John Lautner Archives.

The strategy seemed to work. “They really got us wanting to build something different,” Jaime recalls. “So when I talked to Frank, I said, ‘I wish we could do something that nobody’s even thought of before.’”

But what brought the clients squarely into the architects’ camp was the 71 percent downward-sloping site. To erect a house on such a slope required imaginative engineering, given the limited budget. The unique structural solution at which the architects arrived ensured that the final design would be anything but conventional.

Enter Andrew Nasser, an engineer known for his work on tunnels, high-rise buildings, and Hollywood-specific problems such as the giant snake in the movie Anaconda.

“Normally, architects come to me with their designs already done, but they came to me first,” says Nasser, who in his early days advised Eero Saarinen and later, Lautner. “[Escher and GuneWardena] wanted to know what was the best and cheapest way to support a house on a steep hillside.”

Nasser’s advice was simple: a structural system with the least amount of contact with the hillside. The Chemosphere House has a single pillar holding it aloft, but, the engineer reasons, “This limits your design alternatives too much.” He suggested a strategy for the Jaimes’ home: erect a bridge, two towers rooted deep in the hillside supporting a pair of steel beams upon which the house would securely balance.

Engineering considerations aside, the Jaimes’ limited budget was very much a factor. “It’s not hard to design a fantastic house if you have a budget of $300 a square foot,” maintains Escher. “But to design one that is accessible to anyone who wants to buy the [architectural] equivalent of Ikea furniture—that was something we were really interested in.”

The bridge scheme, calling for eight underground caissons at $8,000 apiece, was relatively economical. (By contrast, the Spanish-style house next door, with almost the same size floor plan, necessitated 27 caissons.) In theory, a budget of $100 a square foot was possible. But the delays imposed on the project by a two-year wait for permits from the city of Pasadena, and the precision with which the house needed to be detailed, led to a final cost of $180 a square foot, or $425,000.

The bridge supports a rectangular floor plan, measuring 84 by 30 feet. The architects took great pleasure in making the most of this box shape. By now they had reached a compromise with the Jaimes. “They realized they didn’t need ‘separate spaces,’ only spaces which could be used for different purposes, and that it was OK to have all the living spaces open and connected,” according to GuneWardena. In fact, the interior reflects Escher and GuneWardena’s obsession with mathematically precise layout.

To ensure that the floating quality of this rectangular space station would always be evident, the architects prevented views of the exterior walls from being blocked by interior walls or doors. So, no room along the house’s perimeter walls is fully enclosed.

The only fully enclosed spaces are deep within the interior of the house: the powder room, a laundry, a second bathroom, and, of course, the garage—which, artfully placed in the middle of the house, separates the eastern, more formal, end of the house from the western section, which contains the kitchen, family area, and children’s bedrooms.

The other design concern, especially for the Jaimes, was how best to frame the extraordinary views. Of vital importance was situating the east and west windows at either end of the house so that from, say, the kitchen counter, the family could take in two different mountain ranges.

The result of all this sometimes-fidgety geometry is to give the 1,965-square-foot house (plus 400-square-foot garage) an expansiveness way beyond that of a traditional home of the same dimensions. When the Jaimes moved from their highly compartmentalized, three-bedroom house in the outer suburb of Tujunga, they were daunted by their new home’s spaciousness. “At first it was hard, walking from one end to the other, but we got used to it,” remarks Rochelle as if she had moved to San Simeon.

From the outside, the house is less subtle. Although its sharp edges are softened by the gray-white texture of its Cempanel siding, the rectangular box appears almost too delicate to warrant the massive supporting towers. In contrast to the Chemosphere House—a space station-like form poised for a graceful liftoff—the light-filled Jaime house, with its heavy foundations, is conspicuously earthbound. The outcome—in which proportions seem somewhat unbalanced—attests to Escher and GuneWardena’s preference for design based on structure more than aesthetics.

It’s the inside that the Jaimes respond to most. And respond they have, taking delight in every inch of space. They had barely moved in before a variety of relatives appeared from Sri Lanka to stay. Parties started happening. The floating box was instantly bursting with life.

There’s only one problem. Life in the house with the fabulous golf course view is simply too hectic. “I haven’t had time to play golf,” laments Bryce Jaime, who confesses that his handicap is on its way up.