The Big Island’s new mayor says there’s no way Hawaiʻi can meet its 2050 deadline for converting the state’s 83,000 cesspools to septic tanks.

Since his island is home to well over half of those cesspools, Mayor Kimo Alameda’s perspective carries weight in the debate over the 2017 law.

“It’s an unfunded state mandate and it’s stressing everybody out… especially on our island,” Alameda told Civil Beat.

The deadline stems from Act 125, which was aimed at curbing tens of millions of gallons of sewage pollution from flowing daily into Hawaiʻi’s ocean and destroying its coral reefs.

Renowned reef expert Greg Asner backs the mayor up, calling the deadline “very pie in the sky.”

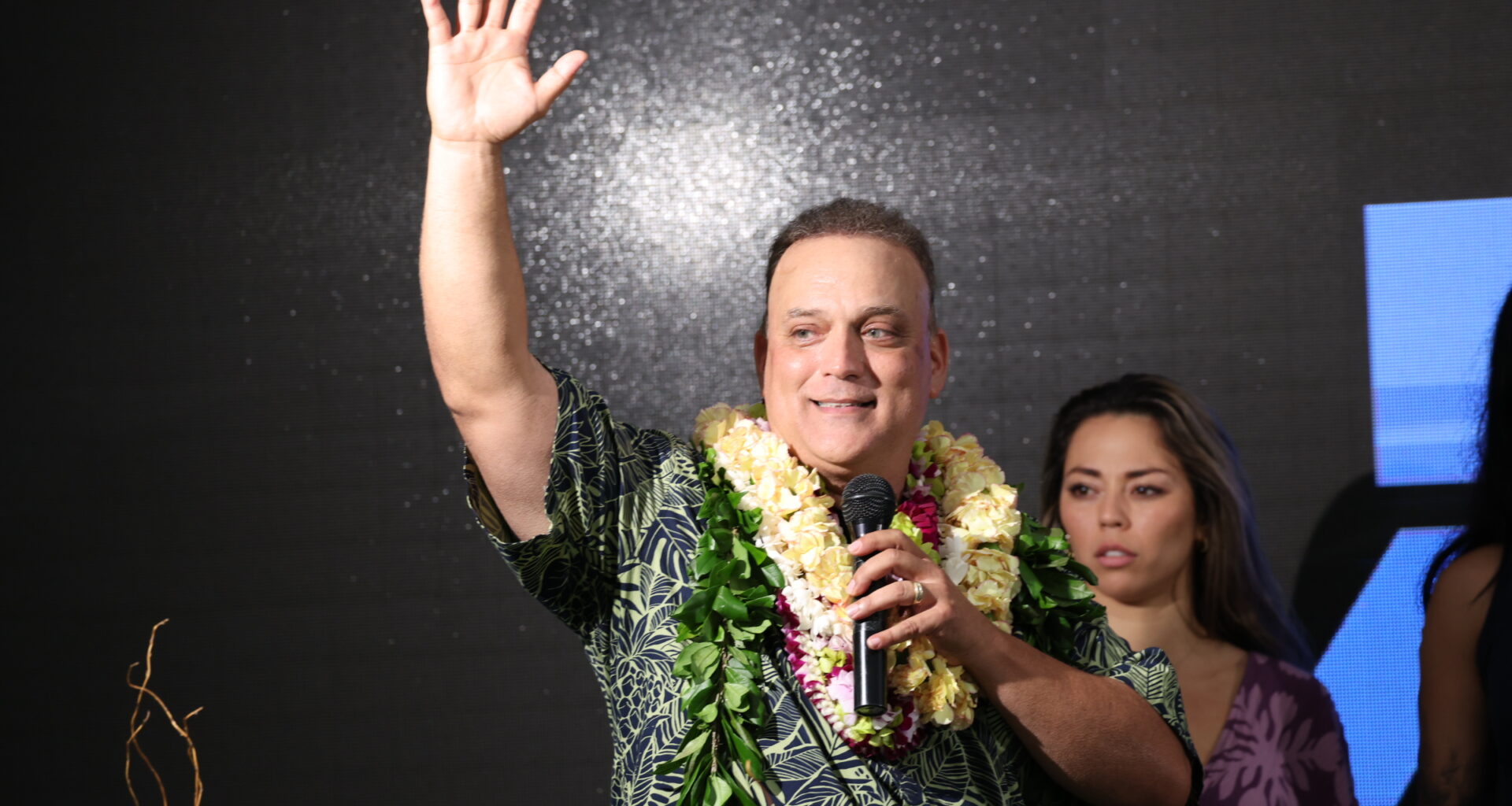

Clinical psychologist and former Big Island rancher Kimo Alameda at his victory party in November 2024 (Cody Yamaguchi/Civil Beat/2024)

Clinical psychologist and former Big Island rancher Kimo Alameda at his victory party in November 2024 (Cody Yamaguchi/Civil Beat/2024)

Alameda’s stance might sound like an about-face from his campaign promise last year to make his island’s waste problem a top priority. But it’s actually a recognition of the depth and scope of the problem.

“In my talk stories when I was campaigning, I said, ‘How dare the feds, you know, give us this mandate without any funds?’” Alameda said. “Come to find out, it’s a state mandate!”

When he found that out, he said he picked up the phone.

“I talked to Josh,” he said — Gov. Josh Green, that is.

Alameda said he told Green he wants to see Act 125 revised. Push the deadline back. Don’t require every single cesspool to be converted. Be strategic.

A portion of Hawaiʻi’s new “green fee” championed by the governor should go to homeowners trying to convert their cesspools in Alameda’s view. Starting in 2026, the new fee increases by .75% the state’s transient accommodation tax to support environmental protection and climate resilience. It’s expected to raise about $100 million annually.

Alameda isn’t depending on the state to do everything either. He’s convening a task force of experts to chart a path forward for Hawaiʻi island, including Arizona State University’s Asner, a Big Island resident.

He also directed the island’s Department of Environmental Management to produce a countywide integrated wastewater management plan by this fall. And he’s meeting with hard-hit communities such Puakō that are actively trying to trade cesspools for modern alternatives.

As much as Alameda would like to rid his island of these noxious pits, he said there’s not enough money to compensate homeowners to make the costly conversions. There’s currently no dedicated fund to help them convert to septic tanks, he said, which typically costs between $25,000 and $45,000.

Nor is there an adequate labor force — the engineers, contractors and others — to do the work.

He suggests the mandate needs some revision. Not all cesspools are alike. Some are too far from the ocean to be problematic and septic tanks may not even be the answer. They also leach sewage, pharmaceuticals and other pollutants into the groundwater, and then the ocean.

“Traditional septic is not really a solution for us,” agreed Susan Jamerson, a rural development specialist on the Big Island who advises communities on wastewater matters. “It really isn’t that much better than cesspools.”

Pollution Threatens Swimmers, Drinking Water

Despite its worldwide reputation for turquoise beaches, coral reefs and tropical fish, Hawaiʻi’s underwater environment is bombarded by substantial amounts of pollution.

It’s subjected to some 53 million gallons of sewage pollution from underground plumes every day, according to state health officials. More than 30 million gallons of that leak into Big Island waters, including at popular beaches in Kona, Waikoloa and Puakō. Those discharges have been traced back to cesspools and septic tanks.

That pollution imperils reefs, fish, seaweed and other marine species, and it exposes surfers and swimmers to unhealthy levels of bacteria.

“We do know that Hawaiʻi has the highest rate of staph and MRSA infections in the entire country,” said Stuart Coleman, executive director of Wastewater Alternatives & Innovations, a leading nonprofit helping with cesspool conversions.

The effluent can also infiltrate drinking water wells. That’s especially a problem in the Puna District, the fastest-growing place in Hawaiʻi.

Aerial view of Hawaiian Paradise Park. (Cory Lum/Civil Beat/2014)

Aerial view of Hawaiian Paradise Park. (Cory Lum/Civil Beat/2014)

A 2014 study of individual drinking water wells in Puna’s Hawaiian Paradise Park neighborhood found just over half contained total coliform, a fecal indicator bacteria, and nearly a quarter tested positive for E. Coli, according to study author Bob Whittier of the Hawaiʻi Department of Health.

Whittier, a source water protection geologist, said he chose Hawaiian Paradise Park because it has the state’s highest concentration of cesspools. With no access to municipal sewer and water, the neighborhood has about 4,300 household waste disposal sites, most of them cesspools.

Despite the many obstacles, meaningful action can and should be taken to protect the reefs, Asner said. Hawaiʻi just needs to get tactical about how it approaches the problem by zeroing in on the worst offenders.

That’s a big focus of his research.

In a 2024 published study, Asner and colleagues identified more than 1,000 places where freshwater percolates into the ocean. After the study’s publication, his team collected samples from point sources on the Big Island’s leeward side, testing for sewage pollution.

They knew from previous research that groundwater discharge is ubiquitous along the West Hawaiʻi coastline. But they wanted to pinpoint the coordinates of the most polluted spots. They did so with high-tech Earth mapping technology from Asner’s airborne laboratory.

Greg Asner, center, is director of Arizona State University’s Center for Global Discovery and Conservation Science. (Nathan Eagle/Civil Beat/2024)

Greg Asner, center, is director of Arizona State University’s Center for Global Discovery and Conservation Science. (Nathan Eagle/Civil Beat/2024)

In a study poised for publication in the journal Frontiers in Marine Science, Asner reveals some new findings.

Some 42% of tested locations had elevated levels of Enterococcus bacteria, he said. Another 23% had concerning levels of the bacteria, commonly found in the intestines of people and warm-blooded animals.

These hot spot sites dotted the South Kona and South Kohala shoreline, including resort areas south of Puakō, parts of Hōnaunau Bay, and at Miloliʻi Beach Park, within walking distance of Asner’s lab.

As expected, the sites with the worst contamination sit below watersheds with high levels of development, with more cesspools and septic tanks, and with greater amounts of barren land.

On a practical level, the research indicates where Hawaiʻi County and the state Department of Health, which regulates cesspools and septic tanks, should direct their efforts.

“Going from strategy to tactics is what I’m all about,” Asner said, “because I’m trying to fix this reef.”

Racing To Beat A Reef’s Collapse

At more than 4,000 square miles in size with many far-flung, rural neighborhoods, the Big Island may never be able to extend county sewer lines to every household. It’s too costly.

Decentralized onsite systems for individual homes or neighborhoods may offer a lower-cost solution.

County Council member Heather Kimball is working with Coleman of Wastewater Alternatives & Innovations on a proposal for a community facilities project in Miloliʻi as a potential alternative. This public-private partnership would be a funding tool to move the community’s cesspools onto a decentralized treatment system.

Assuming the community agrees to tax itself to cover some of the costs, it could be a solution for Miloliʻi, home to a community-based subsistence fishing area of significant cultural importance to Native Hawaiians. And Kimball said it could serve as a demonstration project for other neighborhoods trying to make cesspool conversions a reality.

Many coastal states, including Washington, Oregon and California, are moving away from allowing septic tanks in shoreline neighborhoods, or already have.

“That’s something I think we need to look at too,” Kimball said.

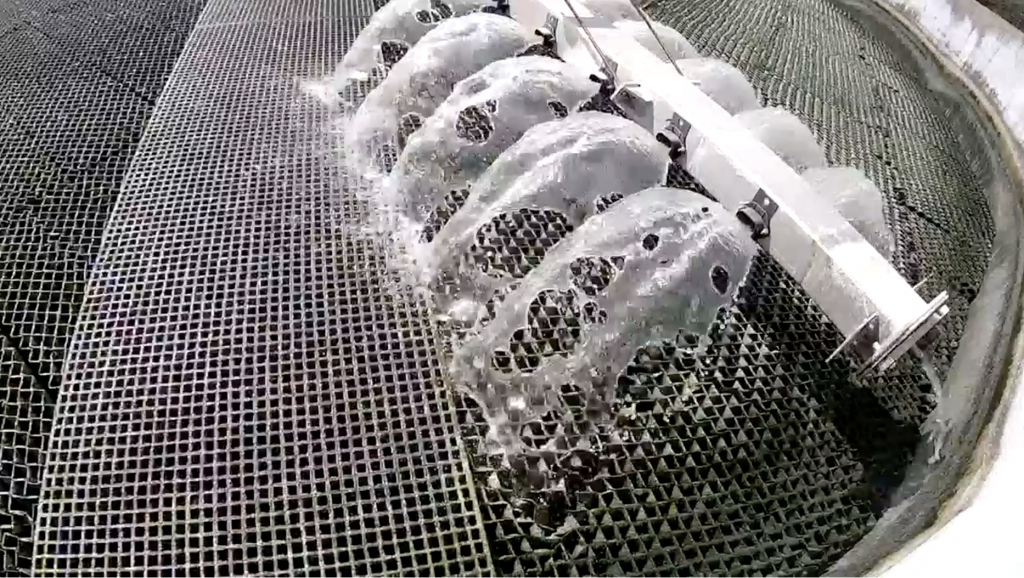

Dye tracer studies starting with cesspools and septic tanks show sewage flow reaches the Puakō shoreline within hours. (University of Hawaiʻi/2021)

Dye tracer studies starting with cesspools and septic tanks show sewage flow reaches the Puakō shoreline within hours. (University of Hawaiʻi/2021)

The community of Puakō is trying to quickly move in a new direction as well, before its reef collapses. Coral coverage on the Puakō reef, a key marker of health, has declined from as much as 70% to as little as 5% in the last half-century, according to various studies.

With a highly degraded reef due to cesspool pollution, residents and the nonprofit Puakō For Reefs are working with officials to establish a community facilities district. Some $3 million raised by the community over the past 12 years has gone toward design and engineering plans, said Karen Anderson, president of Puakō For Reefs and a former director of The Nature Conservancy in Washington State.

If a community facilities district is funded and approved, Puakō wastewater would be collected from cesspools and piped to a treatment plant not far down the coast at the Mauna Lani resort.

Advocates are hoping to get a rural development loan from the U.S. Department of Agriculture to pay for some of it, and for the county to float bonds to cover additional costs. The County Council has already approved a $1 million revolving loan fund for the Puakō project and future ones elsewhere on the island, Anderson said.

Although many county staff responsible for financing and wastewater infrastructure are new to their roles and still in a learning curve, Anderson is encouraged by what she’s hearing from Alameda.

“We were able to get a meeting with the new mayor in January,” soon after he took office, Anderson said. “They’re meeting with us, and they are listening.”

The Nations Largest ‘Unsewered’ City

Beyond cesspools, the Alameda administration is grappling with critical upgrades to Hilo’s dilapidated wastewater treatment plant known for large, accidental discharges of raw or partially treated sewage into Hilo Bay, a body of water that federal regulators have deemed impaired since 1998.

Hilo is the nation’s largest “unsewered” city because up to 70% of houses remain on cesspools, according to a Wastewater Alternatives presentation during a December 2024 town hall.

The county has signed a contract to fix the Hilo wastewater treatment plant. (Hawaii News Now/Screenshot/2022)

The county has signed a contract to fix the Hilo wastewater treatment plant. (Hawaii News Now/Screenshot/2022)

On top of that, having a municipal wastewater plant that the Environmental Protection Agency considers one of the worst in the nation makes Hilo Bay and its surrounding beach parks a questionable location to swim, paddleboard or fish.

Given the precarious state of the corroded plant, Alameda signed an emergency proclamation in February authorizing emergency actions if the plant collapses or discharges a large amount of untreated or partially treated waste. He reupped the proclamation in June and has signed a $337 million contract with Honolulu construction firm Nan Inc. to fix the plant over a five-year period.

A community “blessing” kicked off the long-awaited project this week. Alameda described it as an event to “get everybody all jazzed up and together and, you know, ready to do this.”

Civil Beat’s coverage of environmental issues on Hawaiʻi island is supported in part by a grant from the Dorrance Family Foundation and its coverage of climate change and the environment is supported by The Healy Foundation, the Marisla Fund of the Hawai‘i Community Foundation and the Frost Family Foundation.

Sign up for our FREE morning newsletter and face each day more informed.

Sign Up

Sorry. That’s an invalid e-mail.

Thanks! We’ll send you a confirmation e-mail shortly.