By Rose Hoban

In the wake of congressional passage of the One Big Beautiful Bill Act, which cuts more than a trillion dollars over the coming decade in health and human services spending, North Carolina state lawmakers passed a stripped-down version of a state budget Wednesday that starts to carve millions out of spending on some of North Carolina’s most vulnerable residents.

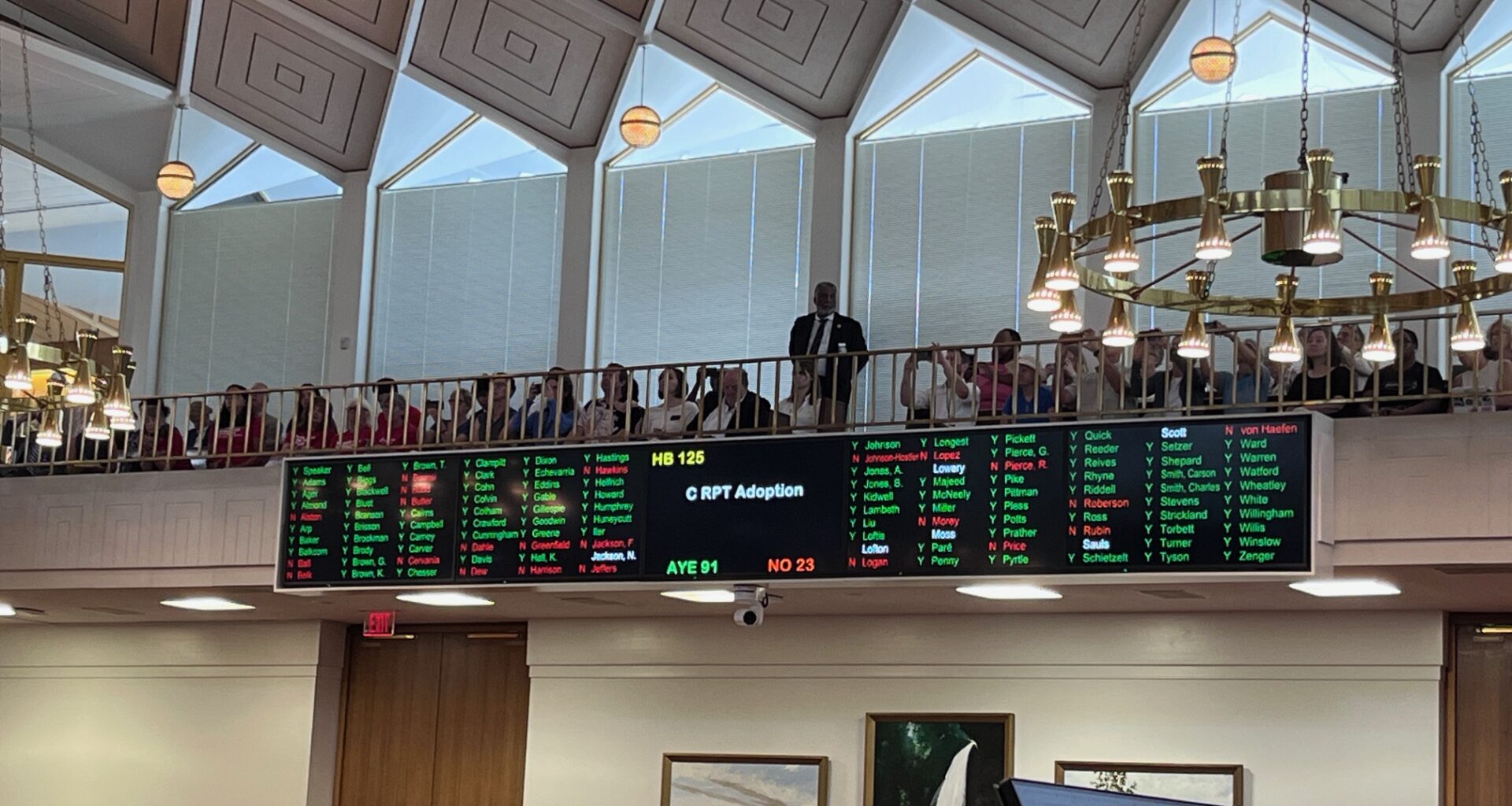

In a vote where about half of the Democrats in the House of Representatives and most of the Senate Democrats crossed the aisle to vote with Republicans, the continuing budget operations bill came in at a mere 31 pages.

Lawmakers had left Raleigh in late June without completing work on the state budget because the Senate and the House couldn’t agree on how to structure the two-year spending plan that should have been in place by July 1, the start of the state fiscal year. Sticking points include the size of tax cuts and the funding structure for a children’s hospital to be built in the Triangle, among other issues.

The initial budget documents that went before the House and Senate this spring tallied more than 1,000 pages. In the document approved this week in both chambers, the “mini budget,” only four pages include health care and social services provisions. And most of those Health and Human Service projects were hit with the red ink pen, slashing funding for mental health, public health and child care subsidies.

“It doesn’t get much more bare bones in our HHS world than this,” said Karen McLeod, who runs Benchmarks, an advocacy organization focused on child and family service providers.

When asked at the end of June whether part of the budget delay was reflective of the budget process unfurling in the halls of Congress at the time, North Carolina legislators waved off reporters. But the lean spending plan rolled out on Tuesday reflects the deep cuts made by Congress that will roil state budgets for years to come.

House budget writer Donny Lambeth (R-Winston-Salem) told his colleagues as he introduced the mini budget before the vote that it was “a step along the path that ultimately leads us to a final budget.”

Financing Medicaid

One of the big ticket items is the Medicaid financing plan, which includes an annual “rebase” that reflects the amount of funding required to maintain current service levels for beneficiaries of the state and federally supported health care plan. This number ticks up every year.

“The primary drivers of the rebase request amount are largely medical cost inflation, scheduled changes in the federal medical assistance program (FMAP), and increased service utilization,” Patsy O’Donnell, a spokesperson for the state Department of Health and Human Services, told NC Health News in an email.

Lawmakers allocated $600 million in the mini budget for the rebase — more than $219 million short of what contracted actuaries have estimated DHHS will need this fiscal year.

O’Donnell noted the new estimation was “an increase from the $700 million request in the Governor’s budget proposal which was developed based on data from January.”

Most of the rebase covers monthly payments to managed care companies that pay for each of the close to 3 million North Carolinians enrolled in Medicaid, she wrote. There are also several recent or new initiatives that have been added by the legislature that are increasing the price tag. Those include:

“We felt like at this point in our process, this was the best number we could go with,” Lambeth told his colleagues before the House vote Wednesday morning. “We do think with all the things going on with Medicaid at the federal level, that we’re going to have to actually spend more time, not only on the rebase number and all the other issues related to Medicaid sometime in the fall.”

Democrats decried both the abridged process for drafting the budget and the fact that their party was shut out of deliberations.

“This just came out yesterday,” Rep. Marcia Morey (D-Durham) said during an abbreviated floor debate. “We haven’t had a whole lot of time to digest and have any hearings with public input on it.”

Morey pressed Lambeth on the $200 million difference between DHHS’ number for the fluctuation in costs this year and the lesser amount in the bill.

“We’ve spent lots of hours on the telephone,” Lambeth said. “We’ve had conference calls talking about the rebase number. I would tell you that it is still a work in progress. We’ve had staff scrub the numbers; we’ve looked at options. We felt like at this point in our process, this was the best number we could go with.

Holding their breath

McLeod and other advocates in the health and human services industry were breathing somewhat of a sigh of relief that lawmakers had at least included the $600 million for Medicaid costs.

Still, another issue looms. How to make up for the hundreds of millions the state is losing from the federal government for the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program, or SNAP. Food assistance programs have been wrestling with how to fill that void.

“They’ve got to find recurring $434 million or so for the SNAP if we want to keep that,” McLeod said.

“Then they have all of these changes to Medicaid that they’ll have to find. I’m hearing it’s about a half a billion dollars,” she continued. “So you’re talking about a billion dollars in state funds recurring they will have to find, just to keep SNAP and Medicaid whole. That’s even before we do a budget.”

And that, McLeod noted, is on top of hurricane relief funds needed for western North Carolina counties still clawing their ways out of the damage caused last year by the remnants of Hurricane Helene. Lawmakers also turned their focus toward raises for teachers and other priorities in the mini budget, even as Republicans want to continue to cut taxes.

In an interview with NC Health News after the mini budget vote, Lambeth said budget writers are still waiting for details from federal officials about what form Medicaid cuts will take.

“The problem with the federal stuff right now is, you had the bill that came out and it was passed, but you don’t have the regulations or the rules,” he said.

Lambeth pointed out a provision of the federal budget bill requiring states to verify employment among Medicaid recipients twice a year. “There’s no rules written about what that is, and there’s no funding,” he said.

“We need a little bit more information before we really dig deep into what’s the real impact on North Carolina,” Lambeth added.

Red ink

Other provisions in the skinny budget also included cuts to mental health services and public health, causing lawmakers to move money from one fund to another to cover those cuts, the state budgetary equivalent of digging for coins among the couch cushions.

For example, the bill repeals a reserve fund created in the wake of former Gov. Roy Cooper’s Mental Health and Substance Use Task Force Reserve Fund that was established in 2016, moving some $41 million to DHHS to make up for cuts.

The mini budget cuts $18.5 million that had been allocated to the state’s four mental health managed care organizations, Trillium, Alliance Health, Vaya and Partners Health Management. In addition to billing Medicaid for some services, those funds also cover mental health and substance use services for people who lack any form of insurance coverage. The budget obligates these organizations to provide the same level of services as last year, even as they’re given less to do it with.

The budget reduces funds for the Division of Child and Family Well-Being by a total of $1.4 million and cuts $10.9 million in funding that goes to counties to help pay for Medicaid recipients who live in adult care homes.

The budget also moves more than $20 million in funds that flow to the state from a nationwide class action lawsuit settlement over asbestos contamination in talcum powder from the Department of Justice to the state’s Division of Public Health to cover costs there.

All of these trims come on the heels of recent federal agency clawbacks and cuts to tobacco control programs, HIV services and tailored suicide and crisis hotline options.

This will be just the first of several challenging budget cycles, as North Carolina lawmakers work to fill the holes created by the federal budget bill. And Lambeth admitted that some of those holes won’t end up filled.

“Those Medicaid cuts are going to be a mess, and we’re going to have to just work right through them,” Lambeth said.

Republish This Story

Republish our articles for free, online or in print, under a Creative Commons license.