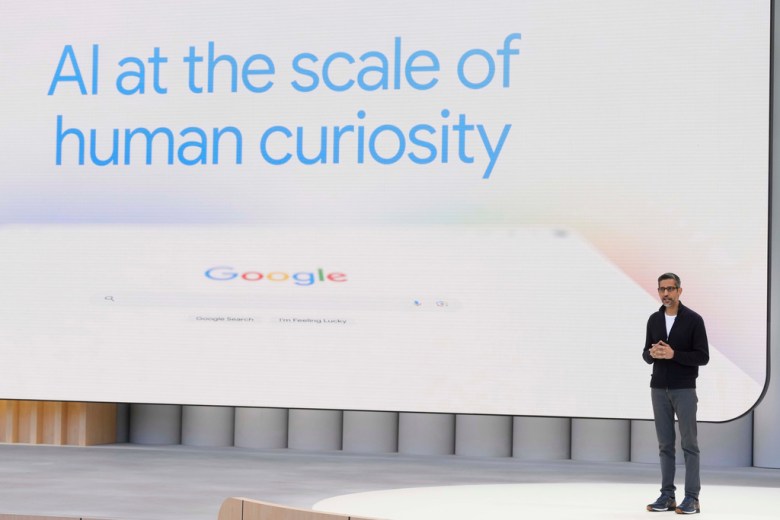

Alphabet CEO Sundar Pichai speaks about Google’s developments in artificial intelligence at an event in Mountain View, CA, on May 20, 2025. (Photo by Jeff Chiu/Associated Press)

Alphabet CEO Sundar Pichai speaks about Google’s developments in artificial intelligence at an event in Mountain View, CA, on May 20, 2025. (Photo by Jeff Chiu/Associated Press)

It’s August, the school year is about to begin, and dread is in the air.

The reason isn’t that the summer idyll is about to end, but AI (Artificial Intelligence) and LLMs (Large Language Models).

Since ChatGPT appeared in 2022, AI is everywhere reshaping everything. From manufacturing to healthcare to engineering, no part of life remains untouched. Many jobs will disappear, we’re told, and even more will be transformed.

Including education.

Schools, both K-12 and higher ed, have rushed to embrace AI. Ohio State University, for example, announced that all incoming students will be trained in AI because, according to OSU’s president, “In the not-so-distant future, every job, in every industry, is going to be [affected] in some way by AI.” The University of Florida proudly announces that they integrate AI “across all disciplines, from healthcare to agriculture and aerospace to the arts.” Same for Arizona State University.

Bringing AI into the classroom leads to “better questions” and “deeper thinking.” Using AI to find and summarize articles means you don’t have to do this yourself, resulting in “liberated time” which can be put to better use.

AI, its boosters say, will do much more than shape how we teach and learn. A tech entrepreneur opined in Time Magazine: “AI promises a future of unparalleled abundance,” enhanced creativity, and social justice though “ensuring fair decision-making, reducing biases, and promoting transparency in governance” in ways beyond human capability. Mark Zuckerberg told Meta’s investors that AI “will improve ‘nearly every aspect of what we do,’” and would usher in “a new era of individual empowerment.”

But we’ve heard this kind of utopian rhetoric before.

The Internet was supposed to end dictatorships. In 1989, speaking in the shade of the crackdown at Tiananmen Square, Ronald Reagan predicted that the “Goliath of totalitarianism will be brought down by the David of the microchip.” MOOCs [Massive Open Online Courses] were supposed to transform education. In 2020, the coronavirus epidemic led to school closures, and tech’s boosters celebrated. Andrew Cuomo, then Governor of New York, with Bill Gates by his side, wondered why we need brick-and-mortar buildings when we have tech to replace teachers. Social media was supposed to lead to a happier, more connected world.

It’s not that tech hasn’t changed our world. Everything, it seems, happens online, and the advantages are enormous. But there are also good reasons for skepticism.

First, the utopian hopes did not come to pass. China, for example, uses the web for political repression, and they are not alone. Social media may bring people together, but according to the U.S. Surgeon General, it also poses “a profound risk of harm to the mental health and well-being of children and adolescents.” Consequently, New York, Oregon, Georgia, and Missouri have banned cell phones from their K-12 schools. Closing schools and moving education online during Covid has led to profound and lasting learning loss. X (née Twitter) isn’t a digital town square, but a cesspool of hate speech, antisemitism, and misogyny.

Next, the companies promoting AI usually have a vested interest. For example, the Deloitte Center for Government Insights published an article last year urging everyone in higher ed to “incorporate and embrace gen AI and traditional AI tools in ways that can enhance efficiency and improve outcomes across the academic enterprise.” A quick Google search reveals that Deloitte has invested $2 billion in AI. So they are not urging colleges and universities to adopt AI out of the goodness of their hearts; they want to see a return on their investment.

Similarly, Microsoft, OpenAI, and Anthropic are investing millions to train K-12 teachers to use AI in their classrooms. The underlying hope is that once kids are introduced to their brand, they will be customers for life.

I’m not saying capitalism is bad. It isn’t. Capitalism is what drives innovation. But as the phrase goes, “caveat emptor,” or, “let the buyer beware,” and when it comes to AI and education, there’s a lot to beware. Because AI can make you stupid.

Studies from both MIT and Microsoft-Carnegie Mellon University (neither bastions of anti-tech Luddism), show that using AI degrades your cognitive skills. For the MIT study, researchers had the subjects write an essay, some using ChatGPT, others not, and they found that the ChatGPT users registered the lowest level of brain activity: “While LLMs offer immediate convenience,” the study concluded, “our findings highlight potential cognitive costs. Over four months, LLM users consistently underperformed at neural, linguistic, and behavioral levels.”

The Microsoft-CMU study showed that the more users employed ChatGPT, the less they examined arguments and came up with their own conclusions:

Specifically, higher confidence in GenAI is associated with less critical thinking, while higher self-confidence is associated with more critical thinking. Qualitatively, GenAI shifts the nature of critical thinking toward information verification, response integration, and task stewardship.

None of this should be surprising. The brain, to state the obvious, is a muscle, and if you don’t exercise a muscle, it atrophies. Which is why AI drives a stake through education’s heart. College is not just about learning content, it’s also about learning how to think about content. AI undermines both by doing your work for you.

If you ask ChatGPT to create an outline for an essay, then you are not learning how to evaluate, synthesize, and organize evidence for yourself. If you use AI to summarize articles, then you are not reading them for yourself. And if you use AI to write your assignments, then you are defeating the purpose of the assignment. Nor are the problems restricted to the humanities. If you use AI to solve your algorithm problems, you aren’t learning how to program.

These are not hypotheticals. By all accounts, resorting to AI is rampant in higher ed. As James D. Walsh puts it in his infamous New York Magazine article, “Everyone is cheating their way through college.”

But instead of skepticism, Mildred Garcia, the chancellor of the California State University System, proudly announced a $17 million initiative with ChatGPT to “Become Nation’s First and Largest AI-Empowered University System.” That’s $17 million at a time of major budget cuts and ballooning deficits for a program widely available for free.

When I asked the chancellor’s office about the MIT and Microsoft studies, Leslie Kennedy, assistant vice chancellor of academic technology, responded, “This is an opportunity for CSU to lead in the exploration of generative AI and its impact on higher education and beyond,” which doesn’t exactly answer the question.

As for the prevalence of cheating using AI, Kennedy referred to a Substack article proposing that students begin with original drafts, then use AI “to refine their prose and expand creative and intellectual possibilities.” But the author also admits that “AI can actually hurt your ability to think creatively by anchoring you to its suggestions.”

Which brings me back to the dread surrounding the start of classes. Not only are students relying on a program allowing them to slide through their classes without doing the required reading, but forbidding AI’s use won’t work for two reasons.

First, AI detection software often gives false negatives and false positives. Walsh fed an AI-generated essay into one such program and it came back as “11.74%” AI-generated. On the other hand, a passage from Genesis “came back as 93.33 percent AI-generated.” There are even programs that will “humanize” AI’s tell-tale airless prose.

More importantly, the CSU administration enthusiastically supports AI, putting teachers in the difficult position of banning something the administration fully backs.

To be honest, nobody knows what to do, but it feels like the end of education.

Peter C. Herman is a professor of English literature at San Diego State University. He has published books on Shakespeare, Milton and the literature of terrorism, and essays in Salon, Newsweek, Inside Higher Ed, and Times of San Diego. His latest book is “Early Modern Others: Resisting Bias in Renaissance Literature” (Routledge).