ASTANA – Kazakhstan’s unemployment rate hit 4.6% as of 2024, Vice Minister of Labour and Social Protection of the Population Askar Biakhmetov said at a July 29 government meeting.

Askar Biakhmetov. Photo credit: Prime Minister’s Office

He noted that the main contribution to employment growth was made by employed workers, whose number reached 7.1 million, while the number of self-employed was 2.1 million.

Biakhmetov described the current unemployment rate of 4.6% as a record low. In his report, the vice minister outlined key labor market trends and the government’s approaches to its development.

“First, there is digitalization and automation. An increasing number of professions now demand digital skills. Second, the rise of platform-based employment and e-commerce. Third, our population continues to grow, which means the annual influx of young people into the labor market is increasing. By analysts’ estimates, this figure will reach 360,000 per year by 2035, creating additional pressure on the labor market,” the official said.

Another challenge is the shadow economy. According to Biakhmetov, as of 2024, roughly 30% of the employed population was not contributing to the pension system. The absence of labor standards in certain sectors also contributes to sustaining informal employment.

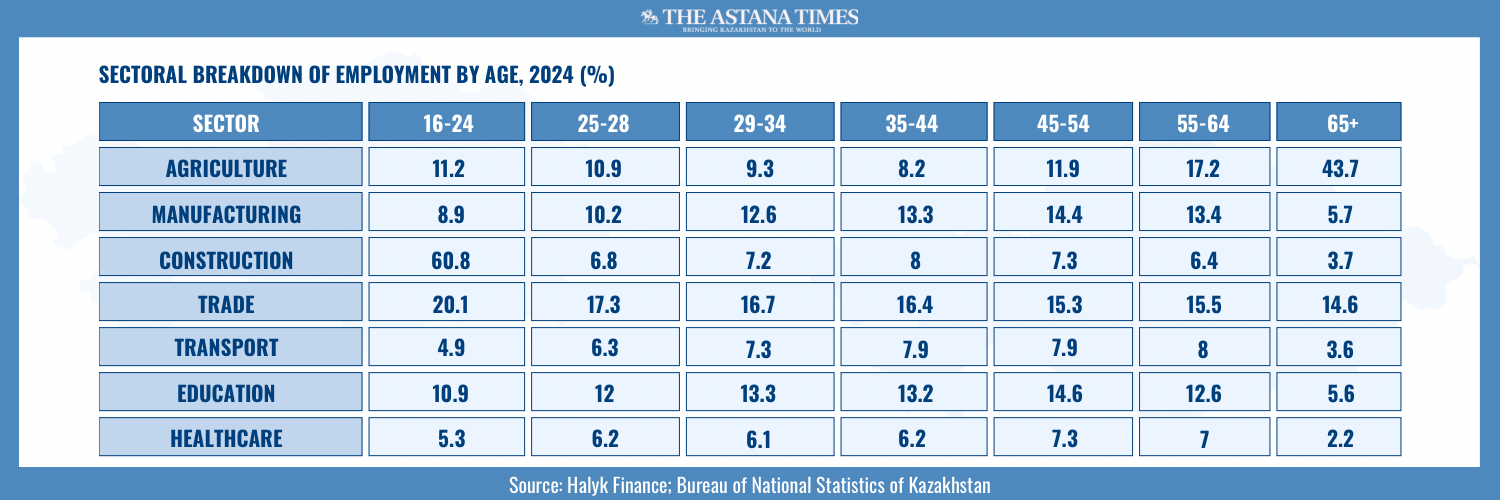

Sectoral breakdown of employment by age. The graphic is designed by The Astana Times.

“The projected demand for workers in the medium term stands at nearly three million people. The sectoral breakdown of this demand shows where efforts should be focused. Public services, including government administration, education, healthcare, and social protection, account for 29% of total labor demand. They are followed by business services (21%), transportation and logistics (16%), industry (13%), and construction and agriculture, each at 7%,” Biakhmetov said.

National targets

Addressing the cabinet at a July 29 government meeting, Prime Minister Olzhas Bektenov highlighted the country’s target to employ 3.3 million citizens by 2030, including 2.3 million young people.

“As part of the Year of Vocational Professions, announced by the head of state, the priority must be to elevate the status of workers and vocational professions. They should meet modern demands. Today, the country is launching large-scale logistics and energy projects. Digital solutions are being rapidly introduced across industries. Taken together, these measures will create new, high-quality jobs,” Bektenov said.

Bektenov also emphasized the need to increase the responsibility of local and foreign investors in meeting their commitments to create new jobs.

To ensure effective oversight of job creation, Kazakhstan has developed an Innovative Project Navigator. This is an information system that tracks the number of new jobs, their alignment with labor market needs, and whether employers are meeting their hiring commitments.

However, at the moment, Bektenov said it reflects only large-scale investment projects across industries. According to the ministry, as of July 29, the system is monitoring 1,415 investment projects with plans to create 222,400 jobs by 2030. Of these, 1,141 projects are in progress, 274 have been completed, and 33,000 jobs have been created.

Bektenov tasked the government to launch a unified information system that will allow real-time monitoring of projects across the country, including workforce qualifications, working conditions, and wages, among other indicators.

State support

State support measures include short-term professional training, business training courses, and grants to start a business. In terms of numbers, in the first half of 2025, nearly 197,000 citizens took part in active employment programs. Of these, 48,100 people enrolled in short-term vocational training courses, 30,800 received entrepreneurship training under the Bastau Business project, 113,700 were placed in subsidized jobs, and more than 4,200 received grants to launch new business ideas.

However, some experts advocate for the revision of state support measures.

“Existing measures, including subsidies and preferences, while yielding positive results, can in some cases weaken companies’ incentives to improve their own competitiveness, particularly when it comes to boosting labor productivity. In addition, without a stronger focus on outcomes, there is a risk that businesses will develop entrenched expectations of ongoing government assistance. This, in turn, can hinder initiative, innovation, and independent growth in the entrepreneurial sector,” writes Arslan Aronov from the analytical center of Halyk Finance, an Almaty-based investment bank.

He suggests shifting policy priorities toward strengthening market infrastructure, investing in human capital, and supporting scientific research, innovative projects, and R&D programs.

Structural challenges

Kazakhstan’s labor market remained structurally vulnerable in 2024.

“While real wages are gradually rising, their growth lags behind the pace of the country’s economic growth indicators and some peers with comparable income levels. Inflation, particularly in the consumer sector, continues to weigh on household earnings,” wrote Arslan Aronov.

Real wage growth remained at 1.7%-2.7% year on year, which is significantly below the pre-pandemic levels when in 2019, the growth was 9.1%.

In 2024, the average nominal wage in Kazakhstan reached 405,416 tenge (US$746). The sectors showing the strongest real growth were finance (+14% year-on-year), telecommunications (+13.7%), and water supply and waste management (+14%).

“In a context where the labor contribution of the population is poorly monetized and wages account for only one-third of gross domestic product, building a fair, dynamic, and sustainable labor market is not merely a matter of social policy but a strategic necessity. First, income regulation must shift toward a more balanced approach. Wage growth should be synchronized with gains in labor productivity, while the overall distribution of income must become more equitable,” writes Aronov.

While Kazakhstan is considered an upper-middle income economy based on the World Bank classification, wages lag behind those of other countries in this category.

“This is explained by the fact that Kazakhstan is a country with a high share of oil, gas, and metal exports. These sectors generate a large share of gross value added but employ relatively few workers. For example, the oil industry can account for nearly 17% of GDP while employing less than 3% of the workforce. Kazakhstan also lags behind three global regions in real wage growth but outpaces the European Union as well as North and South America,” Aronov writes.

Gender pay gap

The gender pay gap also remains relatively high. According to the latest figures from the Bureau of National Statistics, in 2024, men in Kazakhstan earned 26.5% more than women. Their monthly wages stood at 468,914 tenge (US$862) on average, while women’s pay reached 344,496 tenge (US$634).

Explaining this gap, Aronov states that men are more likely to work in higher-paying sectors such as manufacturing, transportation, and telecommunications. At the same time, women are concentrated in lower-paid fields like education and healthcare. Men also more often hold leadership positions, further widening wage disparities.

“Women in Kazakhstan, as on average in the world, tend to have higher levels of education, but the International Labour Organization notes that this is not a significant factor. One important factor is the so-called ‘greedy work,’ which implies readiness to work overtime, travel, and respond quickly to emergencies,” he explains.

Women are also more likely to take breaks in their careers to have and raise children, which affects their opportunities to advance in the career ladder.

“Goldin [Claudia Goldin, recipient of the Nobel Prize in economics] wrote that if a couple has equal earnings before marriage, by the time their child turns 15, the income gap averages 32%. This difference is driven not only by women working fewer hours but also by a decline in their hourly wage,” he explains.

Equal pay is not only a matter of fairness but also a fundamental human rights issue with long-term implications for society and the economy. Narrowing the gender pay gap could expand the economy by as much as 7% over the long term.

Kazakhstan ranked 92nd out of 146 countries in the latest Global Gender Gap Report by the World Economic Forum. This is 16 spots down from last year’s performance.

Kazakhstan’s drop in the rankings is attributed to weaker scores in the subindexes for Economic Participation and Opportunity (61st spot, down 33 places) and Educational Attainment (82nd, down 46 places). At the same time, the nation improved by 13 spots in the Health and Survival subindex, rising to 33rd place. Indicators for Political Empowerment remained stable, with Kazakhstan ranking 117th in 2025.

“It is critically important to address gender inequality in the labor market in a systematic way. Existing programs aimed at developing women’s entrepreneurship, ensuring equal access to high-paying professions, and promoting career advancement must be further strengthened. Increasing employment flexibility, expanding infrastructure to help balance work and family responsibilities such as childcare and day-care centers, and tightening measures against discrimination are all essential elements of this process,” writes Aronov.

No economy has yet achieved full gender parity. Iceland leads the ranking for 16 consecutive years, and remains the only economy to have closed over 90% of its gender gap.

Age trends

In their report, Aronov noted that the structure of employment in the economy demonstrates pronounced age specifics, reflecting both personal preferences of workers and the nature of the requirements of various industries.

For example, in 2024, young people aged 16 to 24 years largely worked in trade (20.1%), primarily in retail. This figure stems from the fact that trade requires a relatively low level of qualifications and experience, offers flexible forms of employment, and is easily accessible in large and medium-sized cities.

“For young people, such employment is often the first opportunity to enter the labor market, acquire basic labor skills and start shaping their professional path. In this case, the trade sector acts as a kind of launching pad for labor activity,” he wrote.

People aged 55 to 64 are more likely to work in industry (13.4%), agriculture (17.2%), transport (8%), and education (12.6%).

“This reflects both higher professional qualifications and a preference for employment that offers clearer career trajectories and social protections,” the report added.