John Brady Balfa is serving a sentence of life imprisonment at the Louisiana State Penitentiary, having been convicted of second-degree murder, armed robbery, and aggravated kidnapping.

On Jan. 6, 1983, at 5:15 a.m., Aubrey LaHaye and his wife, Emily, who were known to their great-granddaughter Jordan LaHaye as PawPaw and MawMaw, were awakened by a knock at the door of their Evangeline Parish home. They opened their door to a man who claimed he was having car problems. As Mrs. LaHaye attempted to phone a wrecker service, the intruder displayed a knife which he held to her husband’s chest.

After Mr. LaHaye gave the intruder $200 from his wallet, the man loosely tied Mrs. LaHaye to the bedpost. He then departed with Mr. LaHaye, who was clad only in pajamas and slippers. At 7:10 a.m., the LaHaye residence received a phone call. The caller demanded $500,000 from one of LaHaye’s sons.

The caller was informed, “We want our daddy back alive! We ain’t gonna pay a dime for a dead man, you hear me?” There was no return call.

Later that same morning, the LaHaye homestead was filled with more than 100 law enforcement personnel of the Evangeline Parish Sheriff’s Department and Louisiana State Police force, who would be joined by a task force of 35 FBI agents who were called to action by way of the Hobbs Act, a federal law prohibiting the extortion of U.S. bankers. Aubrey LaHaye was the recently retired president of the local bank.

Ten days later, on Jan. 16, 1983, LaHaye’s body was found in Bayou Nezpique, 14 miles from his home. In September 1984, 20 months later, Mrs. LaHaye identified John Brady Balfa in a lineup.

A forensic pathologist testified at Balfa’s trial that death was caused by blows to the back of the head by a blunt object. A forensic anthropologist testified that LaHaye had been dead 10-12 days when his body was discovered. A search warrant executed at the Balfa residence found three Camaro tire rims and three mobile home tire rims that, the state’s witnesses claimed, matched the Camaro tire rim and the mobile home tire rim that were found tied to LaHaye’s body. The matching of these rims was the subject of testimony by two special agents from the FBI laboratory, one with expertise in instrument analysis, the other an expert in the examination of tool marks. Another FBI expert testified that the rope used to tie the rims to LaHaye’s body and the piece of rope used to tie Emily LaHaye to the bedpost at her home were identical to rope found at the Balfa workshop. Paint on these pieces of rope was also matched by microscopic analysis.

Balfa did not testify at trial. His attorney called no witnesses. The defense strategy was aimed at trying to discredit the prosecution’s witnesses. The jury considered all the incriminating physical evidence, Mrs. LaHaye’s positive identification of Balfa as the man who tied her up and who abducted her husband, and other circumstantial evidence during the brief time they deliberated before unanimously voting to convict Balfa on all counts of his indictment.

A break in the lengthy investigation into the LaHaye case had happened in September 1984, when Det. Rudy Guillory received a phone call from St. Landry Parish Detective Roy Mallet.

“Hey, Rudy, sorry to be calling so late. I wanted to let you know, today our officers brought us a case of attempted burglary and attempted to murder here in Eunice. The guy came in looking for money, carrying rope and a knife. If I’m not mistaken, that MO sounds a lot like the big LaHaye case y’all have been investigating. Am I right?”

“Who’s the guy,” Guillory wondered.

“His name is John Brady Balfa,” Mallet replied.

Several decades later, Aubrey LaHaye’s great-granddaughter, Jordan LaHaye Fontenot, asked her father, the parish urologist, to fill her in about what happened to his grandfather. Dr. LaHaye revealed that every now and then one of his patients would say, in so many words, “I really don’t think that Balfa boy killed your granddaddy.”

A seed was planted in the author’s mind to fully investigate the crime, the convicted perpetrator, and many other aspects of the case and its aftermath.

In an Author’s Note introducing her book, Jordan LaHaye Fontenot explains, “The story in your hands is built from what remains of a devastating event that occurred thirteen years before I was born. These remnants include old newspaper articles, boxes of documents from the Evangeline Parish District Attorney’s Office, redacted fragments of correspondence records from the FBI’s investigation, the court transcript of the State of Louisiana v John Brady Balfa (1985), and the memories of law enforcement, the community, and my family almost forty years later.”

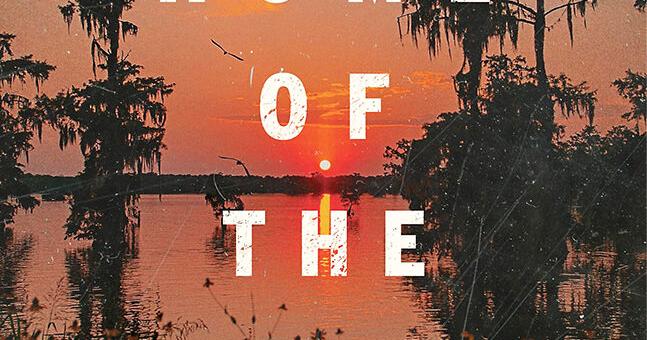

Although “Home of the Happy” is non-fiction, in many ways it reads like a good suspense novel. It is a well-researched, highly readable, and dramatic story that carries the reader from the courtroom to the Louisiana State Penitentiary and to other interesting places in the author’s search for truth.

Her search focuses on several possibilities: 1) Balfa actually committed the crimes against Aubrey LaHaye and that he acted alone in the commission of these violent crimes; 2) Balfa killed LaHaye and was part of a conspiracy that resulted in the kidnapping and murder of LaHaye; 3) Balfa isn’t the man who abducted, robbed, and killed LaHaye but knows the people who were directly involved; or 4) Balfa did not commit these crimes, and knows nothing about the crimes or who committed them.

As you read “Home of the Happy,” you are apt to go back and forth in your opinions of the above alternatives. The author reveals reasons for both supporting and rejecting each alternative. Will she be able to finally satisfactorily resolve all the inconsistencies and mysteries surrounding the violent death of her great-grandfather?

Because I have had some experience in reviewing prisoners’ innocence claims, I could truly appreciate the thoroughness of Fontenot’s search for truth — a search that included wading through the archives of the Louisiana State Penitentiary inmate newspaper, “The Angolite,” in which Balfa is featured in several articles concerning his ministry.

One of these articles is about a Catholic high school retreat held on the prison grounds in 2007. Twenty-five teenagers toured the prison and attended seminars conducted by Catholic inmate ministers, including inmate John Brady Balfa. Will any of these Angolite articles help Fontenot in her search for the truth?

Whether Balfa is innocent or guilty of the crimes against the author’s great-grandfather, he was a violent man before his arrival at Louisiana State Penitentiary. Another important feature of Fontenot’s book is that she grapples with the issue of life imprisonment with no possibility of parole. In their old age, “lifers” have usually mellowed out, often becoming frail and care dependent. If Balfa, who is regarded as “a model inmate,” is unsuccessful in the courts, Fontenot considers whether or not, at some point, Balfa should nevertheless be released from prison on the basis that he is no longer a threat to public safety.