On November 30, 1963, a woman named Karyn Kupcinet was found naked and dead in her Hollywood apartment. The story got stuffed into the back pages of the papers: The mysterious death of a 22-year-old actress with a handful of small TV roles to her credit was interesting, but only so interesting. And the country was still mourning the assassination of John F. Kennedy eight days earlier.

But for Jedidiah Rosenthal, the narrator of Peter Orner’s third novel, The Gossip Columnist’s Daughter, Kupcinet’s death was the equivalent of a nuclear blast. It provoked a generations-long rift between his family and the Kupcinets, who were Chicago newspaper royalty. Karyn’s father, Irv Kupcinet, a.k.a. Kup, was the boldfaced-names columnist at the Chicago Sun-Times, which made him a crucial midcentury entertainment-industry figure. As Orner puts it, “If you wanted to make it in show business in America, you had to go through Chicago, and to go through Chicago, you had to go through Kup.”

For years, the Rosenthals and the Kupcinets were all but joined at the hip. Jedidiah’s grandfather Lou accompanied Kup to Los Angeles to identify Karyn’s body and return it home. But that act of support would prove to mark the end of the pair’s fast friendship. Jedidiah is determined to find out why, but he’s also questioning his own motives. As a college writing professor whose last book came out more than a decade ago, is he just on a desperate hunt for new material? Is he distracting himself from his crumbling marriage? Is he trying to revive a classier, giddier, more socially upscale era in his family’s history?

It’s a little bit of all of that. Orner’s novel is a rich and messy—sometimes deliberately, sometimes not—study of a man compelled to solve both a murder mystery and a more existential one, while wondering if he’s fit for the job. “At best, I’m a haphazard, distractible researcher with an indifferent cat for an assistant,” he muses. But Karyn’s death does offer a novelist plenty of material. She’d parlayed some TV work into a role in a Jerry Lewis film, but evidence found after her death suggests she was cracking under some kind of strain. She abused diet pills and wrote odd and threatening notes to her boyfriend (and, oddly, herself) while filling notebooks with despairing messages: “I’m no good. I’m not really that pretty.”

She was found with a broken hyoid bone, suggesting strangulation, but the chief suspect, her boyfriend, had a clean alibi. The case, in the novel and in reality, remains unsolved, so stories rush in to fill the gap. Indeed, Jedidiah was beaten to the punch by James Ellroy, who accessed the police files for a 1998 GQ article. But Jedidiah isn’t satisfied with his conclusion: “Ellroy’s theory is that Cookie, while dancing naked and ecstatically…(and also loaded and junked-up), fell, and somehow broke her hyoid bone. She then crawled up onto the couch, where she died.”

If only it stopped there. J.F.K. assassination buffs whipped up a story connecting Karyn to her journalist father, who had connections to Lee Harvey Oswald assassin Jack Ruby, who might have told Kup that—well, the red string gets pretty tangled around the corkboard. Jedidiah is sane enough to reject that conspiracy theory, but he’s doing some stringing of his own, suggesting that Kup used his clout to cover up the truth about Karyn’s death, with the help of infamous mob fixer Sidney Korshak, setting off a rift between the Kupcinets and the Rosenthals that’s become Jedidiah’s inheritance.

What Faulkner did for bitter Mississippians, Orner does for glum Jewish Chicago families: In story collections like Last Car over the Sagamore Bridge and novels like Love and Shame and Love, he has specialized in studying the ways families fracture and decline. Daughter is of a piece with that work, thick with earnest laments (“Who else but the Rosenthals would have dropped everything?”), keen observations about the city (“Chicago is giddy for knocking buildings down.… Where’s the money in history?”), and self-deprecating humor. Jedidiah has a habit of talking through his writerly and familial struggles with his cat, who mocks his intentions: “You’re no better than Ellroy. You think you are, Mr. Iowa MFA. Get over yourself, Mr. Literary, the fewer books you sell, the better you think you are.”

Jedidiah, via Orner, isn’t the man to solve the murder, and that inevitability gives the novel its emotional weight. But it also makes it somewhat centerless as it bounces from Hollywood to Chicago clubland history to mob tales to riffs on Saul Bellow. The line between a novelist telling a story about a frazzled novelist and a frazzled novel gets a bit blurry. The cat has thoughts on this, too: “Isn’t your whole point—if you had a point, which you don’t—that families lie to themselves, and that these lies get handed down as love.” A clean resolution was never in the offing—Orner is no detective novelist, and Jedidiah no detective. But both understand families, and the melancholy charm of this novel, which still flashes through all that red string, is that even with all the facts at hand, families will forever be sources of loss, frustration, and mystery.•

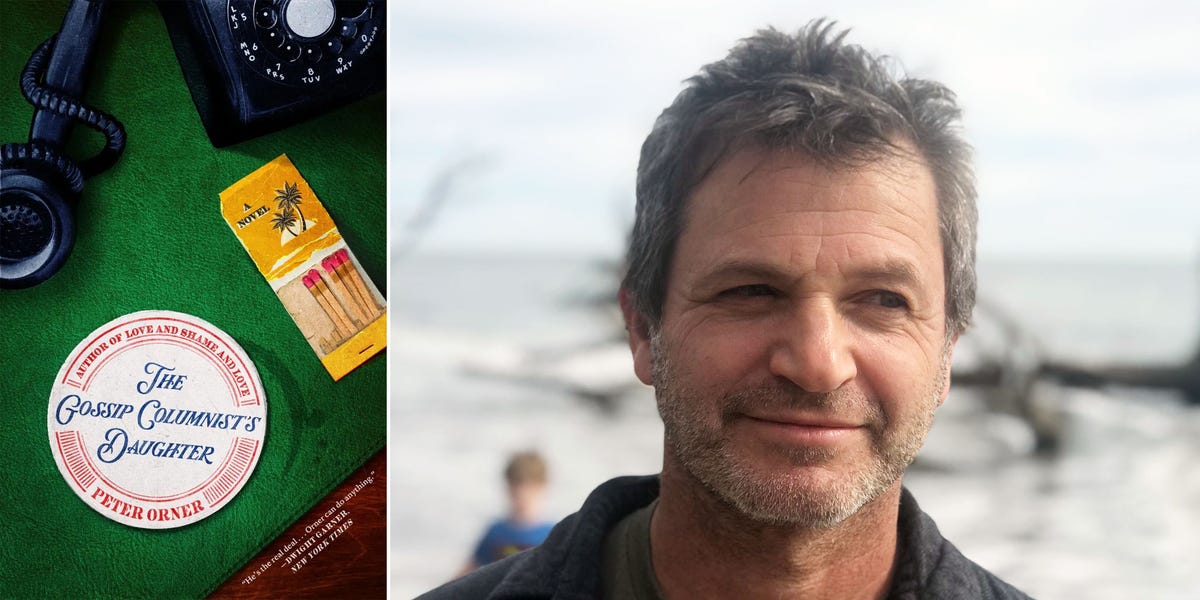

THE GOSSIP COLUMNIST’S DAUGHTER, BY PETER ORNER

Credit: Little Brown and CompanyRelated Stories

Credit: Little Brown and CompanyRelated Stories

Mark Athitakis is the author of The New Midwest (Belt Publishing), a critical study of contemporary fiction set in the region. He lives in Arizona.