What are journalists missing from the state of Delaware? What would you most like WHYY News to cover? Let us know.

Mick Stanziale, who has debilitating cardiac issues and can’t walk 50 feet without getting winded, pays $100 a month toward his $23,000 in medical bills.

At that rate, the 64-year-old Claymont man would pay off his debt in about two decades.

Stanziale’s whopping financial obligation stems from a January 2024 heart catheterization and followup care that his insurance only partially covered. He’s no longer able to work for Home Depot or Lowe’s, his most recent employers, so now Stanziale lives on about $2,000 a month — $1,700 from Social Security and $300 from a small 401(k) account.

Paying for rent, utilities, food and medicine eats up almost all of his income, but each month Stanziale takes pains to send off the $100 check to ChristianaCare, Delaware’s dominant health care provider. He also makes small payments to a fire company for a short ambulance ride he needed last year.

That’s all he can afford.

“The catheterization started the snowball effect,” Stanziale said. “It’s been crazy. Cut me close.”

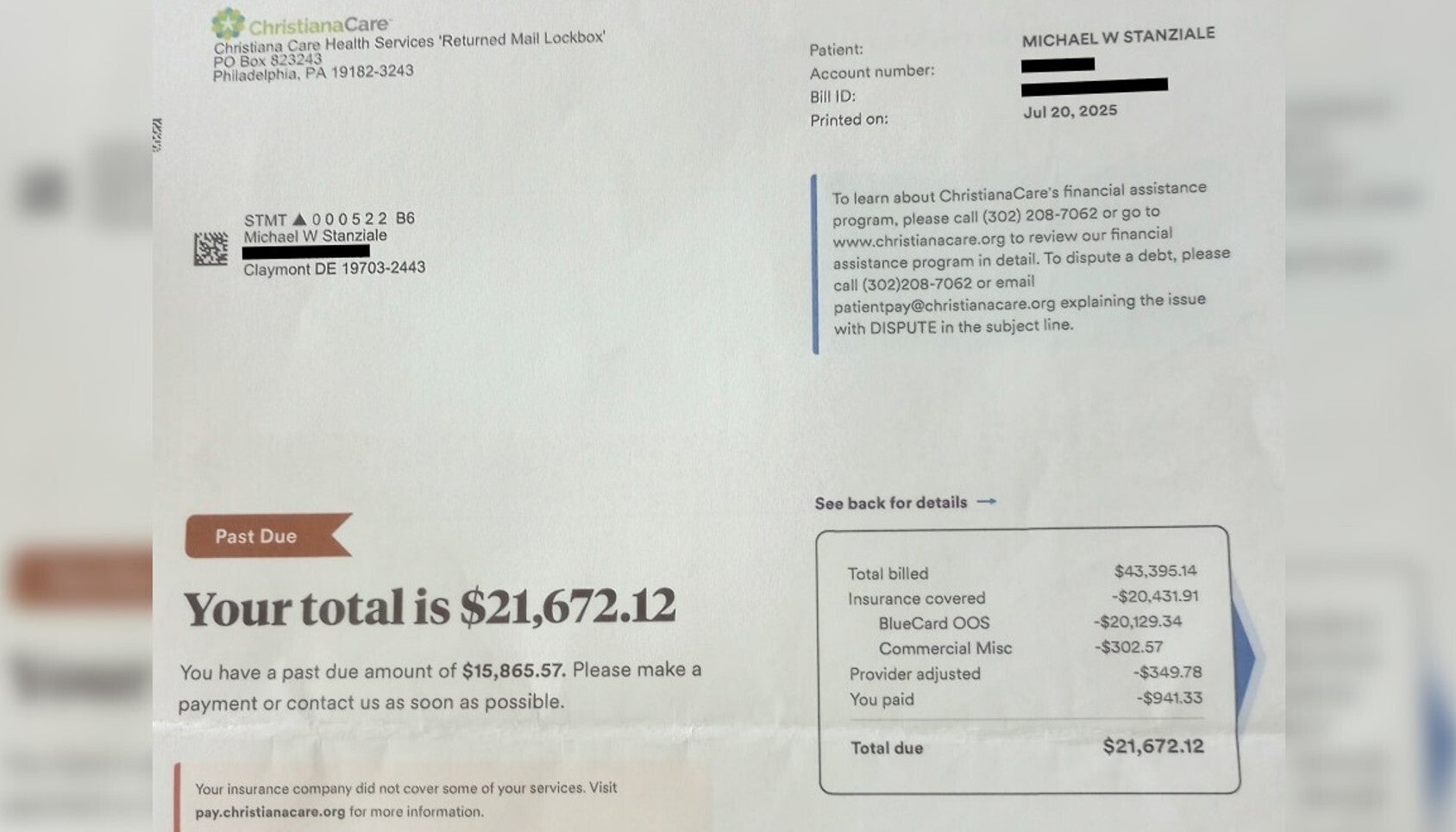

Mick Stanziale pays $100 a month toward his $23,000 in medical bills. (Courtesy of Mick Stanziale)

Mick Stanziale pays $100 a month toward his $23,000 in medical bills. (Courtesy of Mick Stanziale)

Stanziale’s predicament — barely making ends meet while saddled with crushing medical debt — is one shared by thousands of fellow Delawareans.

While the exact amount owed to hospitals, doctors and other medical providers is unknown, the federal Consumer Financial Protection Bureau has reported that in 2020 about 17% of the state’s roughly 1 million residents had $401 million in medical debt on their credit reports.

But Delaware has taken some major steps to relieve the burden so many bear.

Two years ago lawmakers passed a bill, signed by then-Gov. John Carney, that forbids hospitals and other large health care facilities from charging interest and late fees and requires facilities to offer monthly payment plans that don’t exceed 5% of the patient’s monthly income.

That law also forces hospitals and other providers, including ambulatory and surgical centers, to wait at least 120 days after the first bill is sent to the patient to sell debt to a collector, and to notify the patient 30 days before doing so. It stops debt collectors from trying to foreclose on a patient’s property or garnish their wages or other income.

This year legislators went further, prohibiting the reporting of medical debt to consumer reporting agencies and barring it from being factored into someone’s credit report.

Now Gov. Matt Meyer, who succeeded fellow Democrat Carney in January, has partnered with a nonprofit to erase $50 million in medical debt for residents at a cost of $500,000 to taxpayers.

While state officials realize $50 million is only a small fraction of the debt owed by Delaware patients, the Meyer administration is viewing this effort as a pilot program they might seek to expand.

“Eliminating medical debt restores hope, stability, and dignity to people who’ve been unfairly burdened for seeking care,” Meyer said.

The initiative, Meyer said, will help his administration “break down structural barriers that keep people from getting ahead and building the secure, healthy lives they deserve. We’re building a state where your worst day doesn’t define your future.”

The state’s partnership is a three-year deal with New York-based Undue Medical Debt, which buys bundled medical debt portfolios from providers like hospitals, providers and collection agencies at a penny on the dollar or less, depending on how long the debt has been unpaid. Undue has contracts to abolish patients’ overdue debts with about 25 states and localities nationwide, including New York City, Pittsburgh, Connecticut and New Jersey, where more than $1 billion in debt has been forgiven since last year.

Residents of Delaware can qualify in two ways:

Have annual household income at or below 400% of the federal poverty level — $129,600 for a family of four, $62,000 for someone who lives alone.

Have medical debt that’s at least 5% of their annual household income.

Undue plans to buy large portfolios of Delawareans’ debt — perhaps obtaining $1 million worth for $10,000, or less if it’s a few years old — and wipe out the bills of all the qualifying patients in the bundle.

So instead of getting letters, calls, emails and texts from a debt collector or a provider, the patient will get a letter from Undue, notifying them that their debt is zero.

People with debt don’t have to apply or do anything to have their debt canceled.