Most kids who are into Disney—which is to say, most kids in general—typically surround themselves with representations of Disney Princesses. But when Alex Da Corte made his first painting, at age 12, for the walls of childhood bedroom, he instead depicted the characters who antagonize these Princesses. Rather than sleeping beneath Cinderella, her evil stepmother loomed above his feet at night. A smiling Ursula appeared to emerge from a nearby window; Ariel was nowhere to be found.

Da Corte is now in his mid-40s, but he seems no more interested in Disney Princesses now than he did 30 years ago. The only Disney Princess that does appear in his current survey, at Texas’s Modern Art Museum of Fort Worth, is Elsa the Snow Queen, of the “Frozen” movies. She appears as an upside-down standee in A Time to Kill (2016), a wall-hung work that also includes the cardboard from which she was cut, a faux bouquet with a knife stuck in it, two mini disco balls, and a Star Wars Storm Trooper standee. Inverted and left to dangle, this Elsa wears a smile that becomes a frown.

Related Articles

That frown makes sense, because despite the twee reds and pinks of this work’s slats, A Time to Kill is about something horrible: the 2016 shooting at Pulse, in which 49 people were killed and 53 were wounded at the gay nightclub in Orlando, Florida. Da Corte does not explicitly represent that massacre or even directly allude to it, which may just be the point. (And you probably would not know it’s about that subject, either, unless you read the wall text.) He seems fascinated by the notion that Elsa and the multitude of American pop-cultural signifiers with which he works are emblematic of something insidious—even when they seem cheery and fun.

Is Da Corte celebrating all this pop culture or critiquing it? For much of the past decade, I couldn’t tell. It was often hard for me to tell from the camped-up videos in which he dressed up as Frankenstein’s monster, Eminem, and Mister Rogers; the large-scale installations he filled with mod furniture and design objects, such as one that transformed an entire New York building into a haunted house; and the big sculptures he made of witches’ hats and homes. I began to write off Da Corte as an artist more interested in surfaces than ideas as a result.

Da Corte’s A Time to Kill (at right, from 2016) meditates on the Pulse shooting.

Courtesy Modern Art Museum of Fort Worth

How wrong I was. The Fort Worth show convinced me that, in deliberately omitting anything viewers might find too disturbing, Da Corte was mimicking how corporations, movie studios, record labels, and the media push certain people out of the picture, so that we can no longer see them. His work, I realized, is about everything you can’t see because it isn’t put front and center.

Take The End (2017), a print in which a blurry rainbow is sliced into three fragments. Da Corte has intentionally created two cuts that correspond to the edges of Mariah Carey’s body on the cover for her 1999 album Rainbow, in which the arch of colors jumps from the wall behind Carey onto her white tank top. But that smiling pop star isn’t here, leaving this rainbow looking sad and bereft. Excising Carey, a gay icon, could be seen as a violent gesture—especially so for a queer artist—or, perhaps, a campy one not meant to be taken too seriously.

Even more telling is the 2021 painting The Great Pretender in which a pair of hands hold a white top hat surrounded by stars. The hands once belonged to Lily Tomlin, a lesbian comedian who graced the cover of a 1977 issue of TIME magazine in a white top hat for a profile that didn’t mention her sexual identity upon her request. With Tomlin now absent, the painting becomes a statement about erasure—specifically queer erasure—as enacted by the media. What we see in a magazine like TIME is often only a part of the picture.

Alex Da Corte, The End, 2017.

Photo John Bernardo/©Alex Da Corte

For this survey, titled “The Whale” and on view through September 7, curator Alison Hearst has focused on Da Corte’s painting practice, which is a less exhibited part of his oeuvre. That might seem strange, especially given the fact that Da Corte says in the exhibition’s catalog, “I don’t like canvas. I don’t like the feeling of paint on canvas. It sickens me to death.” (This isn’t much of an exaggeration: none of the 60 or so works by him marshalled here are conventional oil-on-canvas paintings.) But the works in this show go a long way in clarifying the sickly-sweet flavors evoked in his well-known video installations.

The show finds Da Corte returning repeatedly to Halloween and horror movies, neither of which seem particularly fun in this artist’s hands. Two of the earliest paintings in the show, both from 2014, feature appropriated images from a website advertising couple’s costumes—one showing a beaming bacon-and-eggs twosome, the other depicting a peanut butter and jelly sandwich combo. Their smiles appear to warp because of the way Da Corte has let this image crumple. With titles namechecking both Jeff Koons’s pornographic “Made in Heaven” paintings and Michelangelo’s Last Judgement, these works feel more than a little evil.

Da Corte’s horror-inflected spirit is also found in 2019’s Non-Stop Fright (Bump in the Night), one of several upholstered works made from foam here. Across its seven panels, the work shows a jack o’ lantern that has been cracked, leaving its grin incomplete and its innards exposed. At least one other soft painting also hints at carnage: The Anvil (2023) takes its form from the steel blocks that typically fall on Wile E. Coyote as he chases after Road Runner.

The Anvil (2023, at right) alludes to images seen in Looney Tunes.

Courtesy Modern Art Museum of Fort Worth

Works like The Anvil seem lighthearted and amiable. But in omitting Wile E. Coyote, Da Corte seems to have something serious on his mind: the ways that certain individuals are scrubbed out and made invisible. So maybe it makes sense, then, that in the only work billed as a self-portrait here—a 2019 painting called Triple Self-Portrait (Study), featuring a painter’s tools stuck in a mug—the artist isn’t even represented at all. And if you’re unsure whether this is a political gesture, check out Untitled Protest Signs (2021), in which pastel-colored monochromes appear in place of activist slogans, a gesture that seems to mimic how the silencing of protesters’ messages by those in power.

The title of Da Corte’s self-portrait appears to reference a famed 1960 self-portrait by Norman Rockwell, which shows the artist painting a self-portrait as he peeks over the canvas to look at himself in a mirror. Rockwell’s paintings helped formulate a distinctly American sense of middle-class identity for many white surburbanites in the postwar era, and Da Corte once said that his father, a Venezuelan immigrant, may have discovered that the US was “Hell” when he arrived there—a far cry from what he might have imagined. The artist described wanting to channel that view in early works, and perhaps he’s done so, as well, in Triple Self-Portrait, which at first glance seems gleeful, then appears eerily vacant upon extended viewing.

Triple Self-Portrait could be read as a negation of a beloved painterly genre, just as Da Corte’s appropriations of pop culture are often negations in their own ways. He’s even curated a nice grouping of works from the Modern Art Museum’s collection for his exhibition. This part of the show is largely centered on the great white males of recent art history: abstractions by Frank Stella, a word painting by Ed Ruscha, a screen-printed gun by Andy Warhol, self-portraits by Robert Mapplethorpe and Francis Bacon. But alongside these works, Da Corte is also showing his own subversions like Mirror Marilyn (2022–23), in which Warhol’s Shot Sage Blue Marilyn is appropriated, then printed backward.

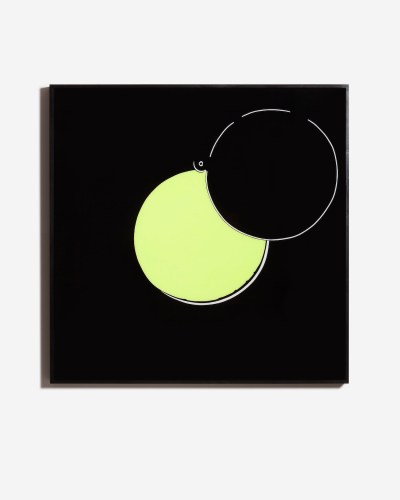

Alex Da Corte, Eclipse, 2021.

Photo John Bernardo/©Alex Da Corte

Edits, deletions, and removals are common in Da Corte’s works about art history. Eclipse (2021) riffs on Roy Lichtenstein’s I Can See the Whole Room…and There’s Nobody in It! (1961), in which those words are painted above a man looking through a peephole. All we get in Da Corte’s take, however, is the peephole itself, with no one there to do the peeping. Da Corte, who is currently in the process of cocurating a Whitney Museum retrospective for Lichtenstein, drains this Pop artist’s work of meaning, then gives it a new one through his title, which suggests that the yellow crescent seen here may represent the moon passing before the sun.

Yet maybe this isn’t all so cynical. Eclipses temporarily leave the world in darkness, leaving people to momentarily find new ways of seeing. Perhaps that is exactly what Da Corte intends to do with his total eclipse of art, which asks viewers to imagine new people to fill Lichtenstein’s empty room.