Brian Dugovich’s colleagues came up with that catchy four-word soundbite — “farming elk feeds wolves” — to sum up one finding from a study he led that investigated the effectiveness of Wyoming’s system of feeding elk in the winter.

Dugovich’s study, recently published in the journal Ecosphere, initially set out to test some of the assumptions about elk feedgrounds and their benefits. One reason why big game outfitters have been steadfast proponents of elk feeding for generations is a belief that feedgrounds improve elk hunting. But it’s a premise that’s never really been tested in the modern era using data.

“We thought it would be a good idea to revisit some assumptions,” said Dugovich, a Ph.D. wildlife disease ecologist who published the study while working at the U.S. Geological Survey’s Northern Rocky Mountain Science Center.

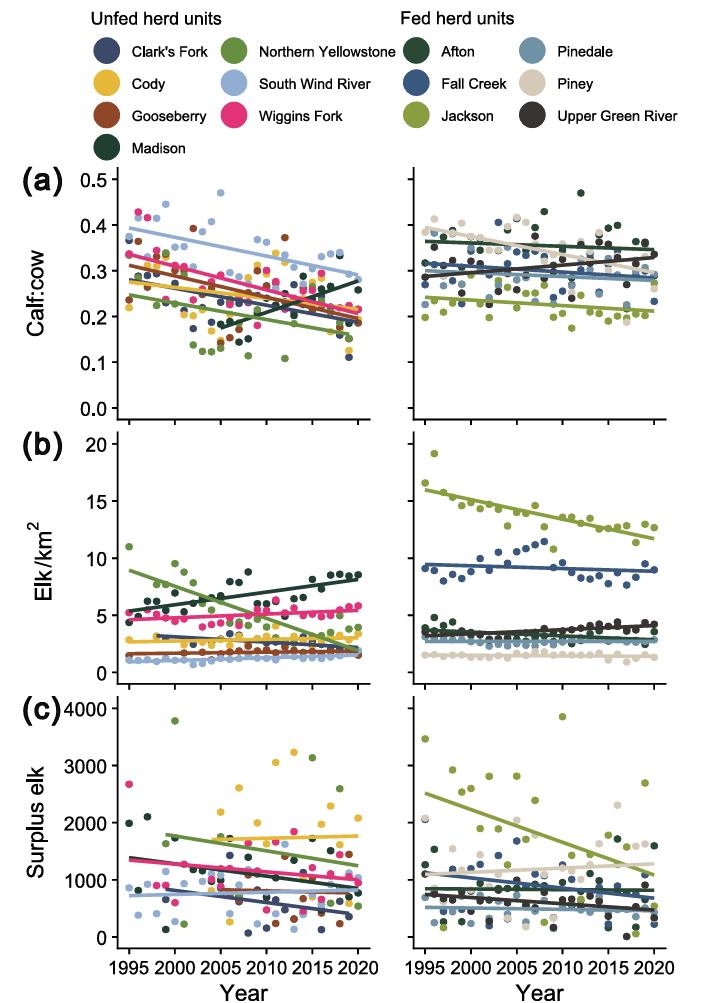

Dugovich and his colleagues examined several demographic indicators for Wyoming’s six fed elk herds, comparing their performance to seven unfed elk herds on the east and north sides of the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem. Specifically, they looked at the rates of calves being recruited in a herd, the population size relative to the acreage of available winter range and the “surplus” of elk, which is essentially the huntable number that could be killed each year without reducing populations.

Demographic indicators illustrated in these graphs suggest that feeding has little effect on elk herd production in the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem. (USGS/EcoSphere)

Demographic indicators illustrated in these graphs suggest that feeding has little effect on elk herd production in the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem. (USGS/EcoSphere)

Results varied — the Jackson and Fall Creek elk herds were more stimulated by feeding than the four others — but overall, the effects of feeding were “small,” said Paul Cross, a USGS research wildlife biologist who collaborated on the research.

“The question then is, ‘Well, why is it so small?’” Cross said. “We’re proposing that it could be that predators are assuming some of that effect.”

In scientific terms, Dugovich described it as a “predator subsidization effect.” In regions where elk are fed hay and alfalfa for months during the brunt of winter, herds brought aboard about 5% more calves than elsewhere in the Yellowstone region. But those extra hooves on the ground didn’t necessarily translate to a larger surplus of elk available for hunting, he said.

“The benefit you might be getting from feeding was being mopped up by the predators,” Dugovich said. “In a more intact ecosystem [that includes large carnivores], the energy you put into the system is going to be harder to get back out again as harvest.”

A lone wolf stands out on the horizon near Bondurant in 2017. (Mark Gocke/Wyoming Game and Fish Department)

A lone wolf stands out on the horizon near Bondurant in 2017. (Mark Gocke/Wyoming Game and Fish Department)

The dynamics were evident in the raw data, Cross said. But a statistical model that was part of the study corroborated the findings, he said. The model used 26 years of data, included thousands of simulations and took into account factors like winter severity and the presence of predators.

The USGS research was conducted in collaboration with federal land and wildlife managers, who shared data. Co-authors listed include USGS’ Emma Tomaszewski, the National Elk Refuge’s Eric Cole, Grand Teton National Park’s Sarah Dewey, Utah State University’s Dan MacNulty, Wyoming Game and Fish Department’s Brandon Scurlock and Yellowstone National Park’s Dan Stahler.

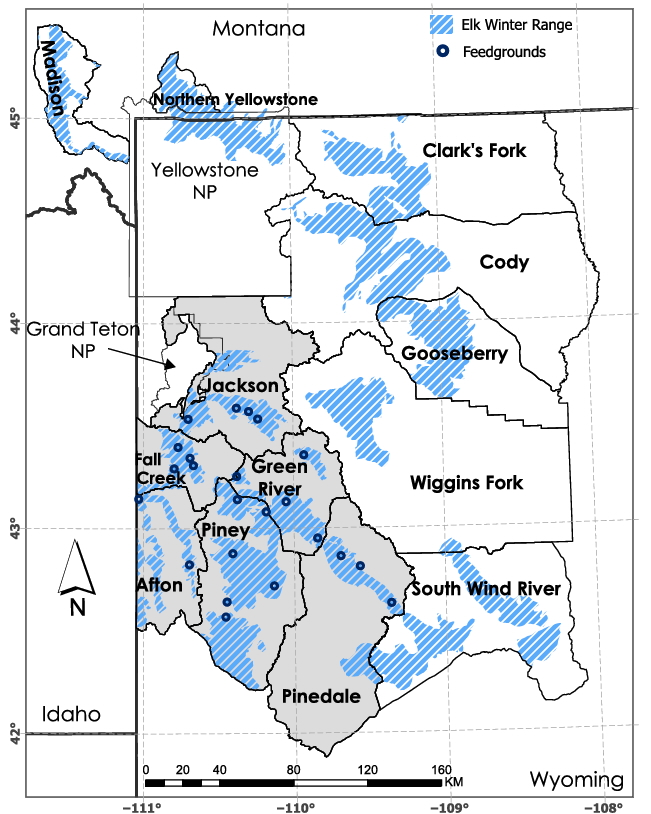

The map shows elk herd units in the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem. Herd units with supplemental feeding are shaded gray, and feedgrounds are marked with circles. (USGS/EcoSphere)

The map shows elk herd units in the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem. Herd units with supplemental feeding are shaded gray, and feedgrounds are marked with circles. (USGS/EcoSphere)

Wyoming Game and Fish, which administers 21 winter elk feedgrounds, declined an interview for this story. Its staff was not involved in the study’s analysis or conclusions about the feedgrounds, which are a political hot potato.

“Game and Fish consistently utilizes the best available data and science to inform wildlife management strategies,” Scurlock, the Pinedale Region’s wildlife management coordinator, said in an emailed statement.

The USGS has been assisting land and wildlife managers with scientific analyses to help inform what they should do about elk feeding in the long run. Although the feeding system is a century old, the recent arrival of chronic wasting disease projects to change the elk feeding equation significantly. Wildlife disease experts anticipate that keeping the historic practice going will produce the worst outcomes for the future of elk populations and elk hunting.

Dugovich’s findings about feedgrounds and elk herd productivity were not included in recent analyses that informed decisions about feeding elk on federal land, according to Cross.

In early August, Bridger-Teton National Forest Supervisor Chad Hudson made a “difficult” decision to keep feeding elk for at least three more winters on the 35-acre Dell Creek and 100-acre Forest Park feedgrounds. A decision about what to do with elk feeding on the National Elk Refuge also looms. Wyomingite and recently confirmed U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Director Brian Nesvik will presumably play a major role in making the decision.