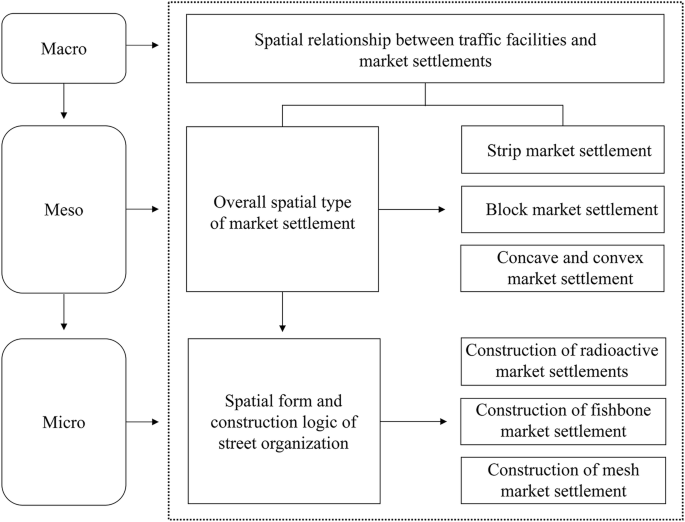

In the process of transforming traditional market settlements into modern urban spaces, the structure of street and alley space serves as the path connecting commercial points. The expansion of street and alley space reflects the dynamic change of the spatial pattern of settlements, boosts the division of internal functional areas of settlements, and significantly promotes the agglomeration effect of economic activities. Meanwhile, street space is also the carrier of local culture and social life, carrying local memories and cultural traditions. Through the superposition analysis of historical maps, remote sensing images, and architectural surveying and mapping data, this study summarized them into spatial forms of the radiation-type, the fish-ridge-type, and the grid-type, and selected typical market settlements such as Chashan Market, Shillong Market, and Guancheng Market for the case study.

Construction of radioactive settlement: Chashan Market

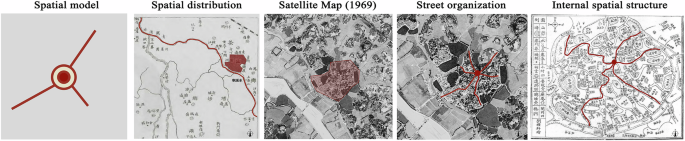

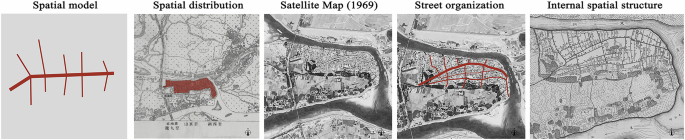

As recorded in the Republican-era Gazetteer of Chashan, the Chashan Market derived its name from the fact that monks constructed Yanta Temple and planted tea in Tieluling over 500 years ago. Its settlement space depends on the water pond and hill landform, forming a radiation-type spatial pattern centered around the Shanggudi Temple. This kind of market layout with temples and ancestral halls as the core is not only restricted by the mountain direction but also sublimates the public space into a spiritual landmark due to folk beliefs. The outward-radiating road system not only connected the clan settlements but also strengthened the cohesion of the settlements by concentrating trade and social functions, demonstrating the spatial wisdom of Lingnan farming settlements of “building according to the situation and gathering people by god” (Fig. 8).

Chashan Market as a Radial Settlement (Source: Self-drawn).

Landscape spatial pattern

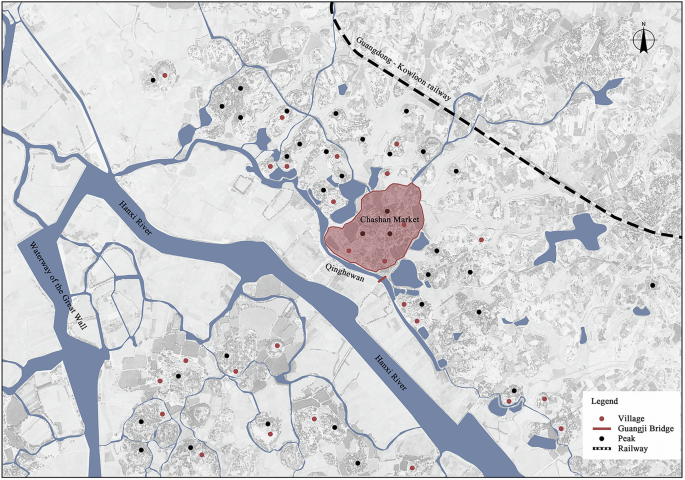

According to the Ancient and Modern records of Chashan, it is described as follows: “In the Southern Dynasty, the area was sparsely populated, and the Tanka people were seen on the river, living by the water, and the pottery fou was the instrument. Sui, Tang, and Five Dynasties, the common people gradually dispersed. Until the Song Dynasty, people from all over the world moved here.” It can be perceived that the villagers of Chashan Market are mainly Tanka, who originally concentrated in the estuary area and took fishing as their business. Chashan Market is close to the Qinghewan water system, and its settlement layout follows the spatial pattern of “back mountain and face water”, which is conducive to agricultural production and water resource management, laying the foundation for commercial development.

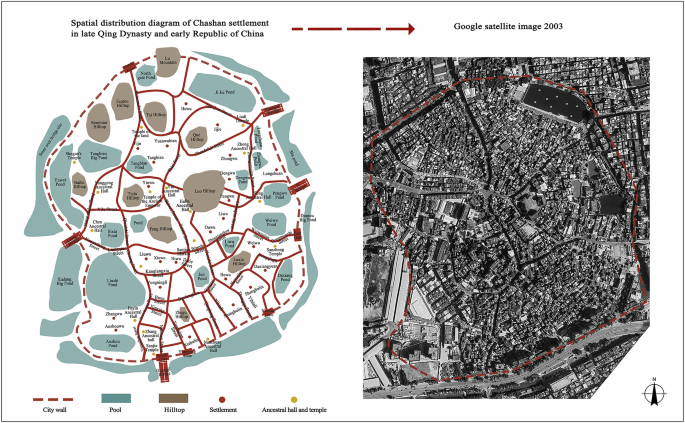

Surrounding Chashan Market lies a strong city wall, which is approximately 1665 meters in total length. Considering the convenience of trade, there are four main city gates in the east, west, south, and north, along with three auxiliary gates (Dongguan Chashan Town Compilation Committee, 2010). Within the settlement, there are 3 hills, 7 ridges, and 18 fish ponds. The whole settlement is divided into 13 blocks, with stone bridges and moats connecting the three main gates to the east, west, and south. Among them, the Guangji Bridge outside the south gate has become one of the most prosperous business districts due to its numerous piers on both sides (Fig. 9).

Geographical location of Chashan Market (Source: Self-drawn).

Street topology

The radial street system in Chashan Market shows a distinct centrality gradient. Within a 50-meter radius of the Shanggudi Temple as the core, Caishi Street, Shiwei Street, and other first-level streets, which are 4–6 meters wide, are paved with stone slabs and equipped with drainage culverts. Their spatial scale and construction specifications are significantly superior to those of other areas. These streets not only serve as the core areas for business activities but also act as the central places for annual festival parades, clan sacrifices, and other ceremonial activities, representing the spiritual symbol of the settlement space (Dongguan Chashan Town Compilation Committee, 2010). The second level street extends to the clan-populated areas, with a width of 3–4 m to meet the needs of daily communication. The public facilities such as well and banyan trees, distributed along the street form secondary central nodes. The third-level roadway penetrates the residential cluster with a scale of 1.5–2 m and realizes the conversion of public and private fields through the transition of gatehouses. Among them, Triangle City is the most frequent location of economic activities in the settlement. On the southeast side of Luoshan, the fan-shaped spatial layout composed by Ou Wu, Wei Wu, He Wu, Li Wu, Peng Wu, Deng Wu, Zhong Wu, and other clan settlements has been preserved until now. The centrality gradient model of Chashan Market shows the spatial power structure of “core leadership – hierarchical penetration” in traditional society (Fig. 10).

Chashan market settlement street space (Source: Self-drawn).

Architectural form and social space

Chashan Markets settlement is built based on the principle of “back mountain and face water”, forming a spatial pattern of a “mountain-dwelling—pond”. According to the records of “Xiang Family Tree”, this place was jointly built by over ten family names such as Tao, Hong, Liu, and Lu. Each clan maintained blood relationships by developing residential areas, compiling genealogies, and building ancestral halls. Taking Lang Village as an example, its spatial texture demonstrates the building wisdom of multi-clan collaboration (Fig. 11). In the north of the village, the Tongshan Mountain serves as a barrier, the Yuan clan ancestral Hall is established in the south to emphasize the clan status, and the four-way village gates, walls, and towers constitute the defense system. The small ponds scattered around the first four villages imply traditional feng shui concepts. In 1737, to conform to the trend of the Tongshan Mountain and Qinghe Bay water system, the residential houses on the west side were shifted 15 degrees to the east, and the Juyin ancestral hall was built on the west side. This adjustment not only ensures that the roadway texture fit with the landscape vein but also strengthens the spatial order through the axis control of the ancestral hall. In the late Qing Dynasty, the clan decided to connect the scattered small ponds into a large one, reflecting the feng shui pattern of “gathering water to generate wealth”. From the guard of the turret, the axis of the ancestral hall to the transformation of the pool, the architectural from has always served the power of the clan. Tongshan and the ancestral hall form the longitudinal spatial axis, while the pond and the roadway form the horizontal connection vein, jointly cast the multidimensional social spatial structure of “Oriented by mountain terrain, united by ancestral temples, and sustained by water as lifeblood”.

Spatial organization model of settlement in Xialang village (Source: Self-drawn).

Construction of fish ridge settlement: Shillong Market

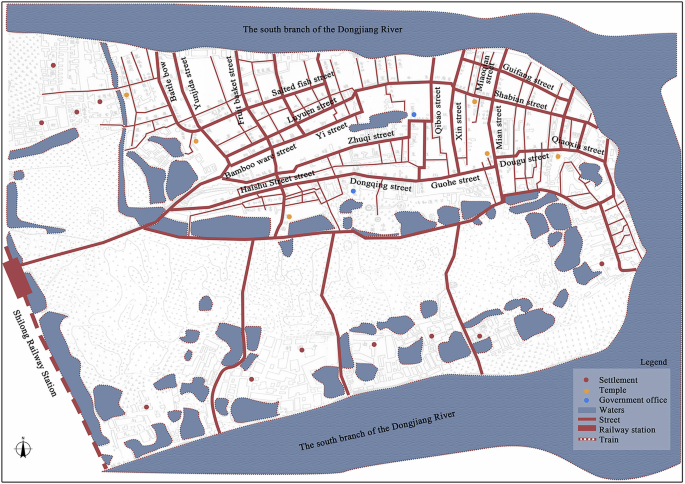

According to the record of the Reconstruction of Longxi Yi Xue, Shillong Market, located thirty miles north of Guancheng Market, controlled the circulation of rice grains and other materials in the traditional era of water transportation by relying on its position as the hub of the Dongjiang River system. After the opening of the Guangzhou-Kowloon Railway in 1911, Shillong Market turned into a transit station for land transportation. As one of the four most renowned towns in Guangdong with Guangzhou and Foshan, its market settlements show a typical fish-ridge layout, with the main road as the “spine” running through the core area of commerce and trade, and the parallel extension of secondary laneways on both sides spreading out like “fish ribs”. The main road mainly concentrates on large shops to carry the main traffic function, while the secondary roadway is distributed with small shops to fulfill the secondary traffic function. This spatial structure effectively guides the flow of people through the hierarchical traffic network, forming a unique spatial form of strip type of market settlements in the era of land and water transport (Fig. 12).

Fish-ridge-type Settlement of Shilong Market (Source: Self-drawn).

Landscape spatial pattern

Shilong Market is situated on the impact plain formed by the confluence of tributaries of the Dongjiang River, surrounded by water systems to the east, north, and south. It faces Boluo of Huizhou and Zengcheng of Guangzhou across the river, forming a settlement landscape pattern surrounded by water on three sides. Located in the heart of Guohe Street, Guanghua Temple was one of the earliest residential areas in Shillong Market due to its high elevation and low vulnerability to flooding. At the end of the Qing Dynasty and the beginning of the Republic of China, as the population increased and the social and economy developed, the area of Shillong Market expanded westward to the Beilian Street area, and the street network began to develop in the northern direction near the water area, mainly to promote the circulation of materials and trade through convenient water transportation. In modern times, the area around Luyuan Street and Shabian Street has become the central area of economic activity in Shillong Market (People’s Government of Shilong Town, Dongguan City (2004)).

Street topology

The centrality of the fish-ridge-type street in Shillong Market demonstrated a dynamic evolution (Fig. 13). Before the mid-Qing Dynasty, Guohe Street, as a main road, reflected in its spatial control, where Ling Wu, Guo Wu, and other clans and LanruoyuanTemple Buddhist places gathered along the street. Together with Zhongwei Street and Zhuqi Street, they formed the center of commerce in the early market. After the Opium War, seven streets on the south Jiulongyong specialized in the cotton textile industry, and streets such as Tingzhu Street and Zhiluo Street formed an industrial belt of bamboo ware. Meanwhile, Guihua Street and Guifang Street developed a cluster of grain warehouses of “upper storage and lower trade” relying on the advantages of water navigation. Between 1900 and 1930, the construction of Zhongshan Road reconstructed the central logic of the street, and the combination of Chinese and Western shophouses widened the street by approximately 8 meters, forming a more pressing commercial interface. The buildings along the street are connected by the space of the portico, making the axis from the railway station to the wharf a symbol of the new spatial power. In 1920, businessmen broke through the traditional South Bank economic belt and built new districts such as Gao Street and Haichun Street at Shiwan on the north bank of the North Main Stream, continuing the tradition of “setting up a city because of water” and breaking through the original topological boundary with industrial expansion (People’s Government of Shilong Town, Dongguan City (2004)). It should be noted that the centrality of traditional streets is more dependent on the geographical accumulation of clan forces, while the centrality of modern streets is obtained through the location advantage of transportation hubs.

Street space of Shilong Market (Source: Self-drawn).

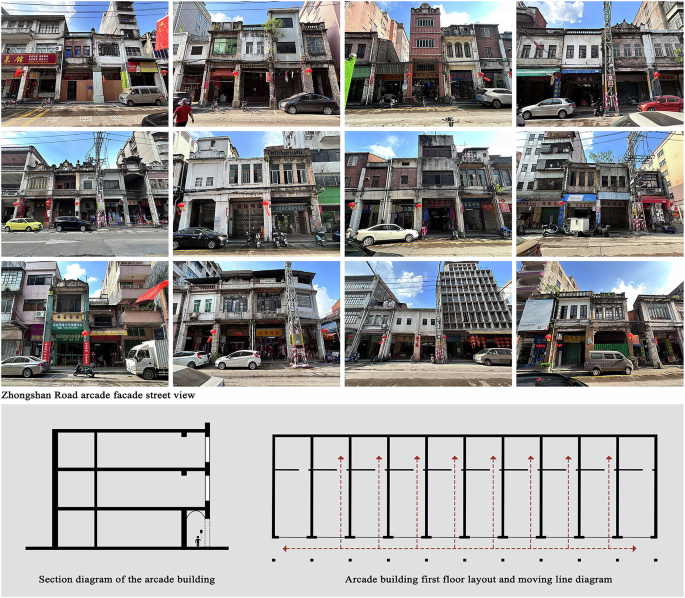

Architectural form and social space

During Chen Jitang’s reign in Guangdong (1929–1936), the construction of Shillong Market reached its peak. The originally scattered Luyuan Street, Wanxing Street, and other nine streets were integrated into Zhongshan Road, forming a business spindle that was 10–16 meters wide and one kilometer long. Zhongshan Road connects the Shilong Station of the Guangzhou-Kowloon Railway in the west and the Dongjiangbei Main Stream Pier in the east. Along it, there are over 500 two-story arcade buildings that combine Lingnan tradition and Nanyang style (Fig. 14). In these “upper and lower bunk” complex buildings, there are not only traditional business forms such as gold shops and cigarette numbers but also modern industrial facilities such as machinery repair factories, which inject modernity into the traditional market space. In 2012, when this section was selected as a historical and cultural street district in Guangdong Province, it still fully preserved eight ancient alleys, 67 historical buildings, ancient trees, ancient wells, and other environmental elements. Moreover, the continuous interface of the shophouses and the transportation axis formed by the railway station and the dock jointly witnessed the spatial practice of the transformation of commercial settlements into modern cities in the era of land and water transportation.

The combination of Chinese and Western shophouses (Source: Self-drawn).

Construction of grid settlement: Guancheng Market

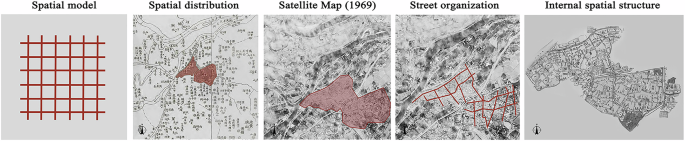

The spatial structure of the grid type is a more complex form that evolved after the expansion of the traditional market. As the market scale expanded, a single linear traffic path could no longer meet the demands of efficient circulation in the market space. Under such circumstances, a more comprehensive road network system began to emerge. It did not follow a fixed template but was flexibly constructed based on the actual needs of the market and changes in the geographical environment, gradually evolving into an irregular grid network. Grid-type market planning often considers specific topographic features, maximizes the functional advantages of different roads through scientific and reasonable street layout, ensures unimpeded flow inside the market, and reserves space for the further expansion of the market. Guancheng Market, the seat of the successive governments of Dongguan with a history of over 1200 years, is a representative settlement of the grid-type market (Fig. 15).

Grid type settlement in Guancheng Market (Source: Self-drawn).

Landscape spatial pattern

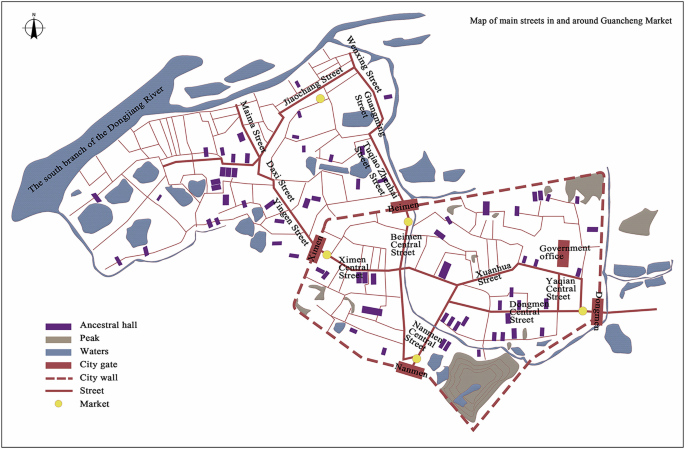

Guancheng Market is a settlement space formed by the combination of Shiqiao Market, Ximen Market, Dongmen Market, Bei Men Market, and Jiaochang Market. According to the records of Dongguan County Annals · Chongzhen, in the late Ming Dynasty, the market settlement of Guancheng Market was divided into three blocks within the city (Fumin street, Guihua street, Dengying street) and one block outside the city (Yingen street outside the Ximen Market), creating a spatial pattern of four interconnected markets both inside and outside the city, which was the preliminary organization of the spatial structure of Guancheng Market. In the middle of the Qing Dynasty, the demand for trade in Dongguan kept increasing. Based on the Jiaochang market outside the city, it gradually developed into a series of commercial blocks, known as “Twelve Square Streets” in Guancheng Market. In modern times, there were 226 streets in Guancheng Market, with 97 were located in the city and 129 distributed outside the city (Dongguan Guancheng Compilation Committee, 2011) (Fig. 16). This spatial pattern not only maintains the stability of traditional functional areas such as government offices and academic palaces but also absorbs emerging businesses such as cloth shops and rice markets through the expansion of dock-oriented streets, reflecting the transformation track of market pattern from closed to open in the era of water transportation.

Street map of Guancheng Market (Source: Self-drawn).

Street topology

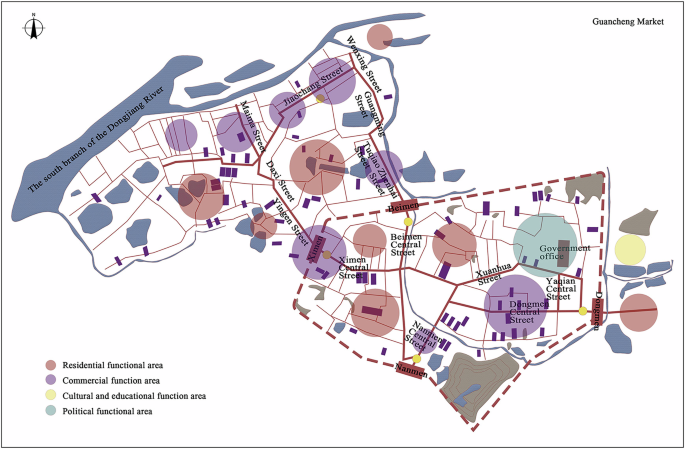

The centrality of the grid street in Guancheng Market has dual attributes. In the administrative grid unit, with the “ritual system” as the main line, the government office area, cultural and educational area, and religious place form the core of the settlement. The ruling order is manifested through the functional division. The government office area is usually located in the center of the settlement space, reflecting the centrality of power through scale control. The street width near the government office area is wider than that of other functional areas, and there is a large activity square in front, constituting a power symbol system. In the business district, centrality is achieved through the composite function. The street along the Shiqiao River is superimposed with two-story shop space, and the commercial center areas such as Ximen Market, Beimen Market, and Dongmen Market are equipped with iconic city towers. This centrality creates a unique tension in spatial governance, shaping the coexistence of government districts, cultural and educational districts, commercial districts, and religious sites (Fig. 17).

Guancheng Market functional zone (Source: Self-drawn).

Motivation of space expansion

Over the five centuries from the early Ming to the late Qing dynasties, the settlement space of Guancheng Market expanded from 0.8 km2 to 3.61 km2. Its expansion was significantly influenced by population, environment, and economy (Dongguan Guancheng Compilation Committee, 2011). According to Dongguan County Records, the population of Dongguan surged from 76,000 to 1,040,000 between 1391 and 1909. This dramatic increase in the labor force led to the formation of dense warehousing areas and wharves in the river plains. As professional markets spread from the city to the waterfront, a cluster of market towns emerged, creating a checkerboard spatial layout of streets and alleys. In the late Qing Dynasty, the water transport system with Guancheng Market as the center and Shilong Market and Taiping Market as the sub-centers was already established, and the composite form of function was achieved through the three-level penetration of shipping, markets, and settlements.